Why does “hati” in BM mean liver, but also heart?

- 428Shares

- Facebook392

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn7

- Email5

- WhatsApp19

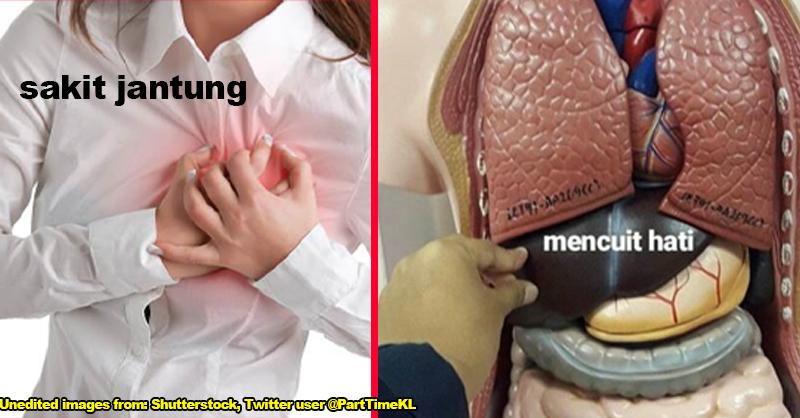

It’s a debate as old as our nation itself (possibly even older): does the BM word ‘hati’ mean ‘heart’, or ‘liver’?

Because even when we asked around the Cilisos office, the answers we got were mixed, with some saying ‘heart’, some saying ‘liver’, and one saying ‘well, no, it’s kinda both’.

But before you start thinking we’re pulling your liver strings, we decided to get to the heart of the matter, and try to find out why we use ‘hati’ instead of ‘jantung’ for emotions.

In ancient cultures, the liver was seen as the center of emotion

Interestingly, the concept of the liver being the center of human soul and emotion can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia (circa 3000 BC.

In fact, there was a whole medical doctrine revolving around the idea of the liver as the center of human and animal emotion, called hepatocentrism. Such was the significance of the liver in those cultures, that it was seen as a mechanism for future-telling (divination). This belief influenced Greek Galenic physiology (which believed that blood was produced in the liver), and persisted in the Western world up until the 17th century when the lymphatic system was ‘discovered’.

However, it turns out that Asian cultures may have gotten it ‘right’ the first time: in Indian Ayurvedic principles, while the liver is seen as responsible for the emotions of anger, resentment, and hate, it’s the heart chakra (anahata chakra) that’s recognized as the ‘seat of emotional experience’.

A similar belief is held by the Chinese (xin/心), Tamil Indians (manase/மனசு), and Thais (jai/ใจ), with all of those words meaning ‘heart/mind’ (more on this later). Arabic culture also recognizes the heart in a similar way, which is why we have the BM word ‘kalbu‘ (from the word ‘qalb/قلب’).

But if other Asian cultures also take the heart approach, well, to heart, why then does the Malay culture diverge from this trend? Well, the answer isn’t so simple, because…

‘Hati’ can mean ‘heart’, ‘liver’, and ‘mind’

Remember earlier on when we said one of our staff members thought it was kinda both liver and heart? Well, he actually had the right idea, and came the closest to the following theory.

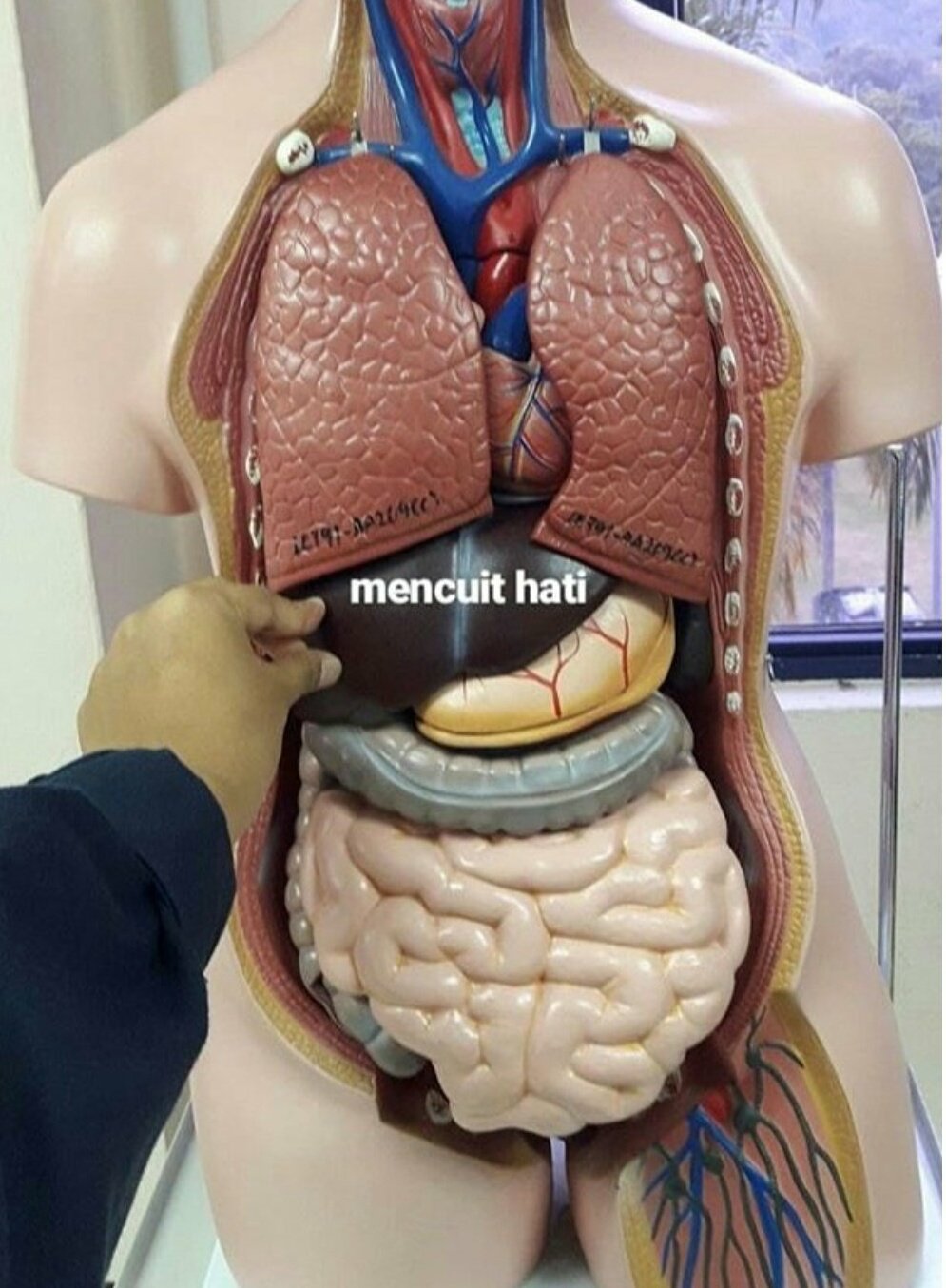

Now, we couldn’t actual find the exact historical origins of the word used in this way, but researchers Dr Imran Ho-Abdullah and Dr Norsimah Mat Awal of UKM provided what we felt was the best explanation: ‘hati’ is the technical term for ‘liver’, but means ‘heart/mind’ in colloquial speak or folk semantics. Therefore, it actually goes in line with the pattern of Asian languages, where the word for ‘heart’ is interchangeable with ‘mind’.

Which kinda makes sense, since we use hati for pretty much everything related to thought, emotion, perception, feelings, passion… it’s a loooong list of things, which is why equally loooong research papers have been written about it (like this one).

As for ‘jantung (the technical term for heart)’, apparently it’s a more recent addition to the Malay language, loaned from Javanese/Sundanese; according to researcher Revi Soekatno, the word wasn’t even contained in the 1983 edition of the Klinkert’s Malay Dictionary. In fact, H.C. Klinkert (1829-1913), who also translated the Bible into Malay, actually used the word ‘hati’ as a technical term for heart in his translation of the King James Bible:

“Maka pingsanlah hatinya dalam dadanya dan iapun menjadi seperti batu adanya (… that his heart died within him, and he became as a stone).” – Samuel 25:37, King James Bible, translated by Klinkert (1879)

The intricacies of Bahasa Malaysia are appreciated by linguists the world over

Despite it being a relatively new language in human linguistic history, it does feel cool to speak a language that’s exclusive to this part of the world. And even so, countless foreigners have researched it, most notably R.O. Winstedt, the Englishman who was so good at the language that he actually wrote a whole three-volume English-Malay dictionary.

But much more than debates on hearts and livers, Bahasa Malaysia represents the uniqueness of our culture, and stands as a piece of our identity no matter how far in the world we go. In any case, we definitely hope you’ll keep us close to your hati… heart, that is.

- 428Shares

- Facebook392

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn7

- Email5

- WhatsApp19