5 legacies Mahathir left for his Malaysia

- 346Shares

- Facebook314

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn1

- Email2

- WhatsApp10

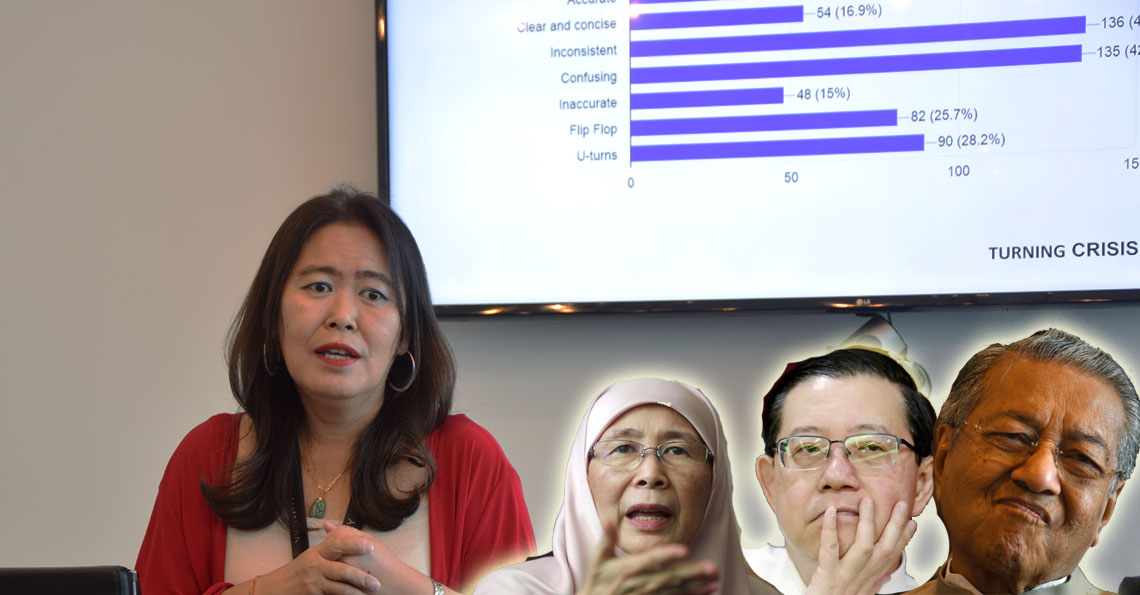

For those who do not know, Dr M has recently been in the spotlight for his criticisms against Najib. Dr M is no stranger to controversial statements or public chastisements – having criticised his first (and handpicked) successor, Badawi, now it seems that he’s doing the same to Najib, also a handpicked successor.

Some might say, ‘people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones’, but sadly, it seems that Dr Mahathir is the only one with any stones left.

Lately, the situation has put Dr M in a strange, ironic position as an ‘opposition leader‘, with some NGOs even asking for him to be investigated for sedition. One of the reasons behind this is that even way past his pension age, the old man still has significant clout. Even Najib took our former PM seriously enough to respond to Dr M’s criticisms on TV3 (albeit seemingly safe, PR-driven answers as commented by many unmoved viewers), and we’ve had wave after wave of anti- and pro-Mahathir comments reaching our inboxes…

Is Dr M worthy of criticising Najib after the track record he left for himself? What does he have to gain at 90 years old? Why is he even meddling in these events? Does he love the country, or just power?

While some people have taken extreme sides in this Dr M vs Najib battle, we at CILISOS decided to revisit several parts of Dr M’s legacy.

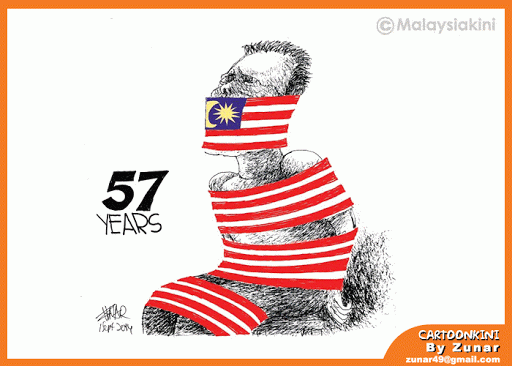

1. Freedom of speech (or lack of it)

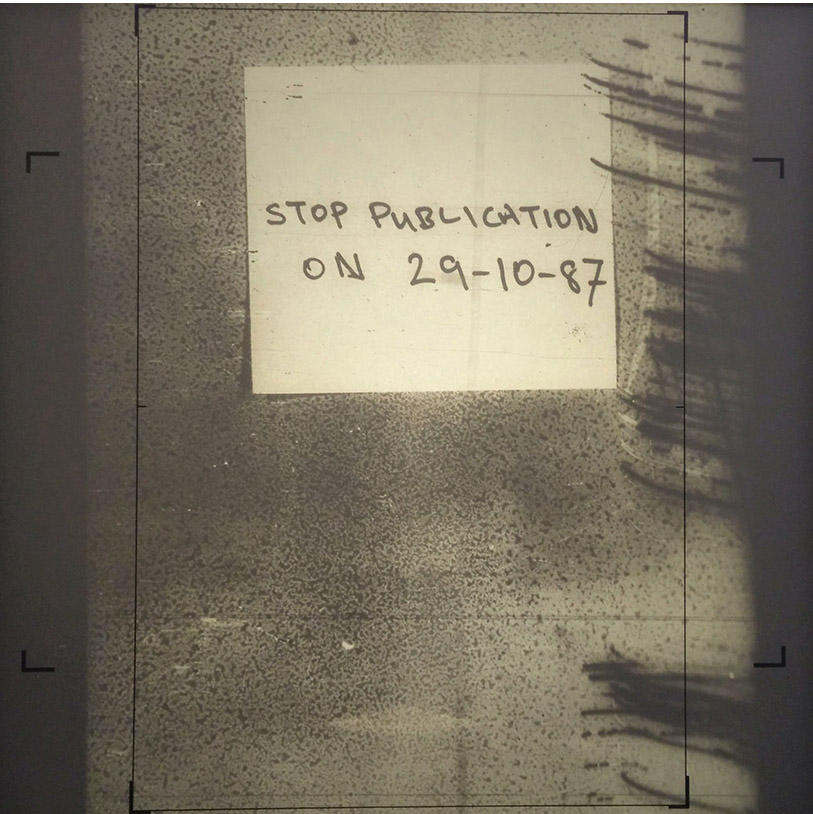

Before 1987, it’s hard to imagine but Malaysian journalists were fearless. Today, many hold their thoughts in fear, afraid of penning anything down that would put their freedom at stake. What on earth happened?

It all began with Operasi Lalang in October 1987, where over 100 people including NGO activists, opposition politicians, scholars and more being detained under the now-defunct Internal Security Act 1960 (ISA). Daily newspapers The Star and Sin Chew Jit Poh also had their license revoked, along with The Sunday Star and Watan (more on that later).

In fact, it wouldn’t be wrong to call it the darkest part in Malaysia’s history of democracy.

It was also during this time when ISA was heavily abused, seemingly having strayed from its original intention of fighting bad communist people.

But… what does Dr M have to do with all this? In 1966 (before he was PM, when he was only a member of the Dewan Rakyat) he spoke against the ISA:

“No one in the right senses like(s) the ISA. It is in fact a negation of all the principles of democracy.” – Dr M, 1966

But that statement seemed null and void through its massive use for Ops Lalang. Supposedly to prevent May 13th from happening again, it’s widely believed that Ops Lalang was designed to control his political opponents.

Through Ops Lalang, the Printing Presses and Publications Act (PPPA) was also amended to ensure tighter control, i.e. renewal of publication permits annually. Sorta like your car license but this one harder to jalan. Why? Cos the license must be granted by the Home Affairs Minister himself, who is given absolute discretion to grant and revoke licenses. There’s also an ouster clause to prevent the actions of the home minister from being questioned by the courts. (!!)

While the act was designed to maintain genuine news stories (among other good stuff), it has been criticised for squashing freedom of speech in Malaysia as it exerts total control over the print media, creating news that are biased towards the ruling party.

The PPPA, along with the ISA, left a fearful atmosphere among Malaysian journalists who felt that Dr M ruled in an authoritarian manner. Here’s what former Star journalist Chong Cheng Hai said:

“In my experience there have been occasions when the owners or publishers held back certain reports and interviews …One was an exclusive on alleged abuse in detention centres of illegal migrants, that had to be cancelled and printed copies destroyed after the media owner read the reports.” – Chong Cheng Hai (Former Star journalist), quoted in Selangor Times

[Side note: While Najib got rid of the ISA, you should really check out Uihua’s story on the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) cos this new act is incredibly scary.]

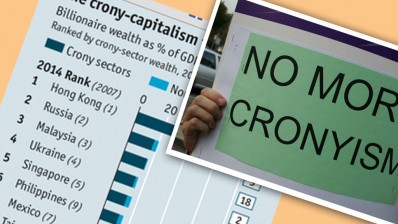

2. Racial policies and cronyism

Part of Dr M’s legacy involved a huge bit of racial policies resulting in cronyism, among others. Now, a long time ago, back in the 1971, the New Economic Policy was born. Although not Dr M’s brainchild, the NEP was meant to last for 20 years. Having stepped into office as PM in 1981, it was his duty to inherit the NEP and make it work for Malaysia.

Here are the NEP’s two grand goals: eradicate poverty and restructure society so that race identification could be eliminated through rapid economic growth.

So, how do we fare today? Check out these stats from a Malay Mail Online report:

- 82.5% of Malaysians below 30 earn less than RM3,000 a month as of September 2013

- The Malaysian median household income stood at RM3,626 in a 2012 Household Income Survey

- And Malaysia’s Gini Coefficient Index measuring income inequality showed that at 0.431, we were one of the worst in the region – worse than Thailand (0.4) and Indonesia (0.37), yo!*

*(0 = perfect equality, 1 = perfect inequality)

On a side note, non-Malays too struggled through these policies – many felt the need to leave the country to look for opportunities in foreign lands. It’s no secret that educational and employment opportunities are rare for non-Malays.

Critics have said that through the years, the NEP seemingly created a class of Malay capitalist, as though being abused to incubate a group of Malay entrepreneurs. The use of the policy was greatly criticised for loading entrepreneurs with huge governmental deals, making the rich richer and the poor poorer… Resulting in Malaysia having one of the worst income disparity level in the region.

To add to this, he was also seen as supporting cronyism, where he pooled a major part of the nation’s wealth in the hands of a few. Just to be clear, this included millionaires who were non-Malays. (If you’re new to the scene, ‘cronyism’ basically refers to ‘the appointment of friends and associates to positions of authority, without proper regard to their qualifications‘.)

So what were the effects of this? A writer summed it up easily:

“[It] left the ordinary Malays and Malaysians with just a few crumbs to share amongst themselves, a slow-boil situation that has blown up to today’s red-hot disputes about social and economic fairness.

Not only is there not enough money for scholarships, education, healthcare, employment and welfare for everyone, even the Malays who have been repeatedly told by Mahathir’s Umno party that they will get priority, have left in the lurch.” – Nawawi Mohamad, plucked from Hornbill Unleashed (2012)

Although, to be fair, Dr M has in recent times logically defended himself (albeit admitting favouritism as well). Watch from 0:00 till the 2-minute mark:

3. Stabilising our economy (in 1997)

During the Asian financial crisis, many countries within the East Asia region were affected. In essence, the counties that really chow tut were Thailand, South Korea and Indo… The rest of us managed to either find shelter somehow (very technical, dunno how to explain also), or at least bounced back without suffering too badly.

Wikipedia tells us that by the end of 1997, the ringgit had lost like 50% of its value. From USD2.50 to USD4.57, ok… That’s worse than today’s value of USD3.67!

So what did Dr M do? Despite the mess that was the NEP, he made a decision to peg the Malaysian ringgit to the USD during the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

If you’re an economic n00b like this writer, it basically means that the value of the ringgit was maintained at USD1 = RM3.80. Die die also maintain. If our ringgit goes down a bit, then the federal reserve would pump in money to bring it back up to match RM3.80. [Edited to reflect correct currency. Thanks Andrew!]

So essentially, it stopped our ringgit from fluctuating, stabilising it so that certain people would (allegedly) stop playing with it, and investors wouldn’t leave the country. It also limited capital outflow from the country. When the currency was eventually unpegged in 2005, it rose as high as 3.16 versus the US dollar (which was admittedly not doing too well).

Critics said that Dr M only wanted to protect his cronies and that the country bounced back because we were ‘lucky’ enough to be in the middle of the rising demand of electric and electronic exports. But no matter what, the result is undeniable – our economy made it through the crisis, recovering quickly so much so that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) called it was a smart move.

4. Putting Malaysia on the map

As Dr M wanted to move the focus on agriculture to infrastructure, these iconic projects put Malaysia on the map. Quite literally, they made us tall, giving us visibility to the world. Kinda like standing on a table in a crowd, only with jaw-dropping architecture and beauty.

Dubbed the architect of modern Malaysia, Dr M made sure that these showpiece buildings would set us apart from other third world countries in our region. Not just for tourism and economy sake, but for our national pride and identity.

But although most Malaysians take pride in it, these projects have consequences to Malaysia’s financial resources. Dr M’s adversary, the late Barry Wain, said that Dr M ‘burnt’ over RM100 billion on various projects with varying degrees of success and failure. A point to note though, Dr M got pretty pissed off and said that he reserved his right to sue Barry Wain for libel. He also added:

“Altogether I don’t think the amount lost added up to RM10bil even,” said Dr Mahathir.

But was it worth it? That’s a story for another day.

5. Teh Internetz

Perhaps one of the best parts of his legacy was the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) program which was officially inaugurated on February 1996. The MSC program basically opened up a whole new era for us. Aimed to accelerate the objectives of Vision 2020, it gave us the technological infrastructure which serves as the foundation to the modern Malaysia you see today.

In the long run, we’ve become relatively advanced in information technology, opening up avenues for innovation so much so we’re in the middle of this startup explosion. SEA is where venture capitalists are looking at, and Malaysia’s a strategic option in this untapped region.

Although, at the same time, Malaysians are questioning whether the amount of money invested in this was worth it. Are we as advanced as we’re supposed to be? There’s especially been much disappointment after Shell broke news that they’d be moving their IT unit from Cyberjaya to Bangalore.

But businesses and all aside – MSC also comes with 10 Bills of Guarantees (BoG), including one we’ve been debating about for a bit:

BoG 7: To ensure no censorship of the Internet

Remember point #1 about printing permits? This BoG was the loophole for the media. Cannot get permit? Go online lor.

And such was the case with journalist Steven Gan and his colleague, Premesh Chandran. In November 1999, Steven and Premesh started an independent online news site free from governmental controls. This site is none other than Malaysiakini, which till this day, is still denied a printing permit.

Through this loophole, many found their gateway to balanced discourse and news coverage. From news sites to blogs, there’s plenty of resources for anyone in any side of the political divide. Plus, there’s CILISOS too!

But to be fair, although the gomen can’t censor the internet, they can block sites (see how here! Also a CILISOS story which ironically started cos Dr M’s site was ‘down’). And with not-so-friendly laws such as the POTA and newly-amended Sedition Act, you can pretty much consider the WWW worse than censored: zero critiques, all cat pictures. 😯

– ———- –

Dr M may have some seriously controversial policies, and he may have made decisions publicly considered as mistakes. But with the recent calls for Najib to step down, we wonder – why would he fight now, at 90 years old, with all the money in the world? The man has everything to lose, and nothing to gain. Is he craving power, or does he reprimand because he genuinely loves Malaysia?

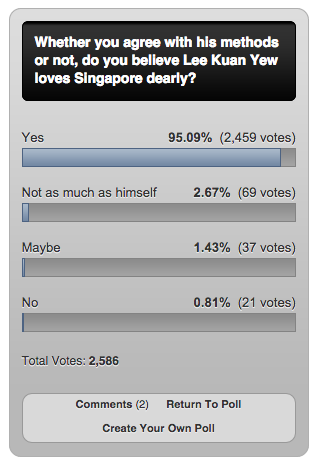

At this point we’d like to draw comparison to the late Lee Kuan Yew, whose policies were equally controversial and had similar principles to Dr M. In our story ‘The Man who wouldn’t let race stop him from uniting Singapore‘, we asked our readers if they believed LKY loved Singapore dearly. The result:

Yes, we recognise the very different outcomes of both administrations (our currency difference is testament itself), but they’re both undeniably similar in some ways. So Malaysia, what do you think? Take our poll:

- 346Shares

- Facebook314

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn1

- Email2

- WhatsApp10