The meeting in 1952 that changed Malaysian racial politics forever

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn3

- Email2

- WhatsApp33

PS: If you’d like more stories like this, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group 😀

Hey! Hey! Wanna hear a joke?

Q: Why are Malaysians so good at using two keyboards at the same time?

A: Because we always stereotype.

Terrible jokes aside, last year, we had the opportunity to watch Road To Nationhood, an incredibly detailed 2-hour documentary on History channel by Rack Focus Films, that sheds some invaluable light into the complex love-hate relationship between the Malays and Chinese of Malaya. We’ve always wanted to write an article about it, but the recent rifts between MCA and UMNO today (which somehow ended up with MCA deciding to stay in BN btw) finally got us off our arses. And so to start, let’s first take a look at…

How the Japanese convinced Malays to strive for independence

To get a good picture of how bad things were at the start, we’ll need to get into the Proton DeLorean and travel back to when the Japanese were occupying Malaya during WWII. While the Japanese troops were in charge from 1942-45, there was a stark contrast between how they treated the Malays (whom they saw as fellow Asian upstarts), and the Malayan Chinese (whom they saw as their war enemy, China).

With the Malays, they were friendly, often putting them in administrative roles, and even stoking early Malay nationalism, with the message that they didn’t need European masters to drive the nation forward. As for the Chinese, there were horrible tales of extreme cruelty, land grabs, rape and so forth. This didn’t help the two races feel at ease with each other.

In any case, the independence that the Japs promised the Malays never came about, as they would surrender in 1945 before anything could happen. But the political turmoil didn’t end there.

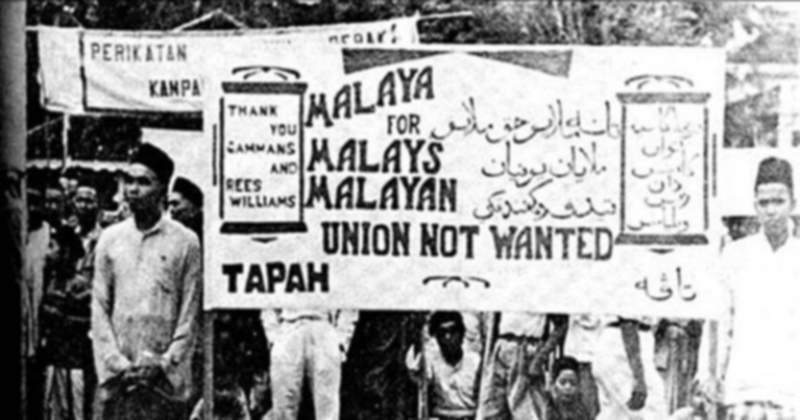

When the Brits came back to Malaya following World War 2, they tried to implement the controversial Malayan Union, a concept that gives Malayan Chinese and Indian workers citizenship, as well as curtails the roles of the Malay aristocracy. To counter this, prominent Johor politician Datuk Onn Jaafar formed United Malay National Organisation (UMNO) in 1946 as a means to rally Malay support to challenge the Malayan Union. He would succeed in some way, managing to convince the royals to not attend the inauguration ceremony – a symbolic move representing the Malay rulers’ rejection of the Union. The Malayan Union would later be dissolved in 1948.

That same year, the Malayan Communist Party (primarily made of Malayan Chinese) who felt betrayed and sidelined after helping the British fight the Japanese, picked up their guns again, leading to the start of the Malayan Emergency. This led to the formation of New Villages – splitting Chinese villagers and relocating them to stop them from supporting the MCP with shelter and supplies. This unintentionally fractured the already fragmented Chinese community.

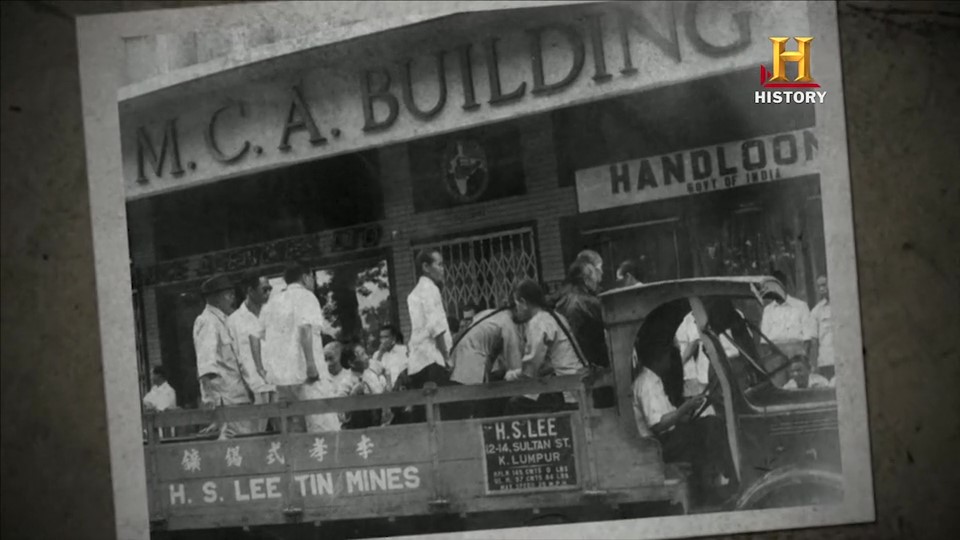

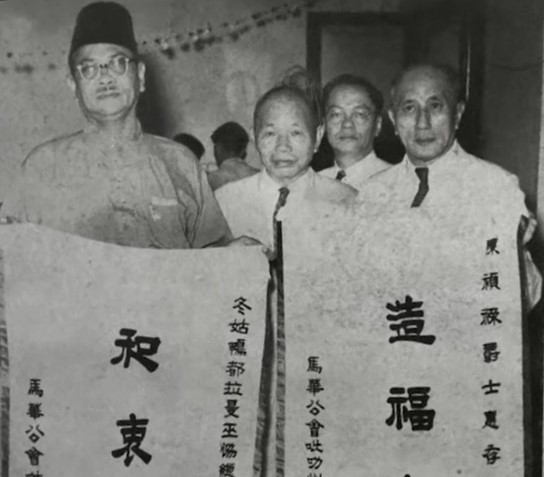

But not all Chinese Malayans were happy with the MCP. Tan Cheng Lock, inspired by Gandhi’s non-violent independence movement, was determined to unite the Chinese to uphold their interests in a peaceful manner. Together with another eminent tin mining magnate, H. S. Lee, they brought together 72 Chinese guilds and associations, and formed the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA).

The British seemed happy with that, as that meant that the Chinese people had an alternative to the Communist Party to support. Tan would lead the MCA nationwide, while H. S. Lee led the Selangor faction.

And here was the moment that shaped Malaysian racial politics forever

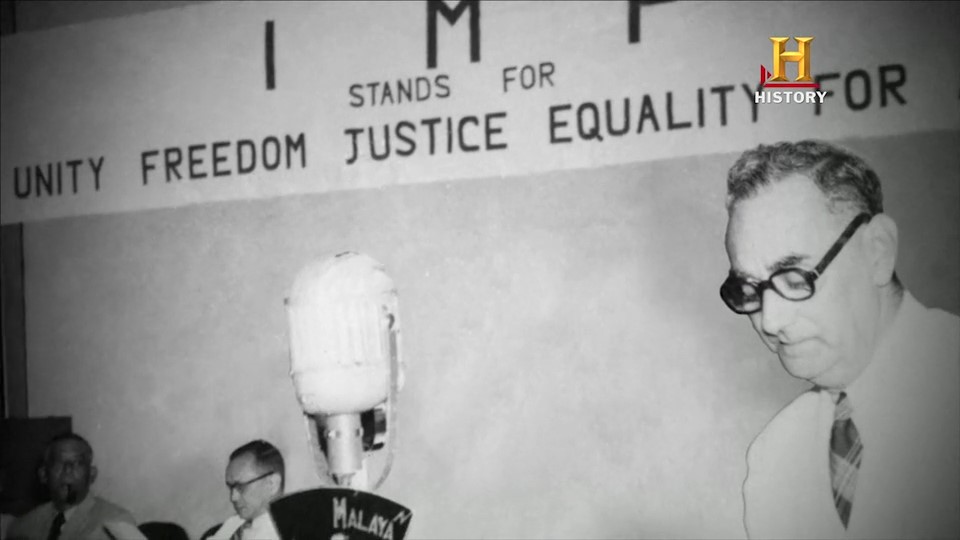

After a few years of leading UMNO, Onn Jaafar had begun to believe that the only way to prosper as a nation would be to unite all the races, not just the Malays. He controversially proposed that UMNO be a party for all Malayans, and for it to stand for United Malayans National Organisation. Sadly, this move was rejected by the majority of party members, leading Onn Jaafar to leave UMNO and form the multi-racial Independence of Malaya Party (IMP). You might be familiar though, with Onn Jaafar’s replacement.

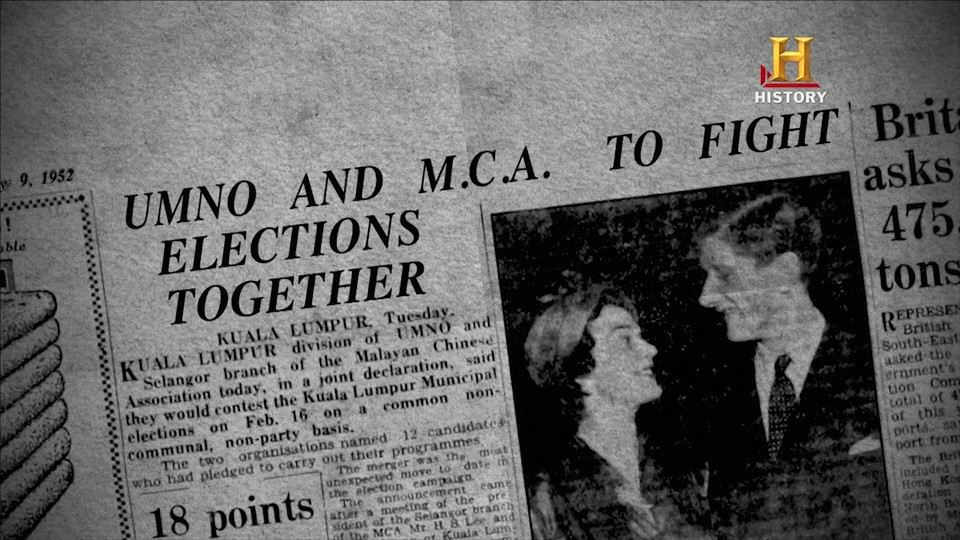

Tunku Abdul Rahman was a royal rogue, known at the time as a ‘playboy prince’ who could charm the socks off anyone. A skill that would come in handy as the Brits continued to slowly allow Malaya more and more autonomy. In 1952, they announced that there would be municipal council elections for Kuala Lumpur, the first of its kind here. The main contenders? UMNO vs the newly minted MCA-IMP alliance. But Tunku’s UMNO was so short of funds – that he had to sell a number of shophouses to generate funds for the party.

The MCA had loads of money, and Tan Cheng Lock agreed with the IMP’s vision of a united, multi-racial Malaya. However, when the IMP decided that all candidates in the coalition must campaign under the IMP banner and logo, H. S. Lee was concerned that the Chinese community would not vote for the MCA if they used the logo and banner of the multi-racial IMP. As such, the IMP-MCA alliance ended, with H. S. Lee preferring MCA to go at it alone than use the IMP banner.

Then an MCA guy got lost in KL and bumped into an UMNO guy

One day, MCA member Ong Yoke Lin got lost wandering around KL, and bumped into his former schoolmate Yahya Abdul Razak, who also happened to be the head of UMNO Kuala Lumpur. After having a quick meeting and chitchatting about the good ol’ days, Ong brought up the possibility of an alliance between the two parties.

“This was the first time politically, with Ong Yoke Lin as the agent, to link UMNO with the MCA into an alliance,” – Dato Douglas Lee, son of H. S. Lee, as quoted from Road to Nationhood

This time, H. S. Lee believed in the idea strongly, and quickly sought Tan Cheng Lock’s blessing to make the UMNO-MCA Alliance official. Despite H. S. Lee’s enthusiasm, Tan and the British were kinda wary and skeptical; they still preferred Onn Jaafar and his IMP’s multiracial party. On the other side, Tunku too had doubts as to whether two racially-based parties could work together.

However, it turned out to be an election winning match – UMNO’s numbers, matched with MCAs financial backing.

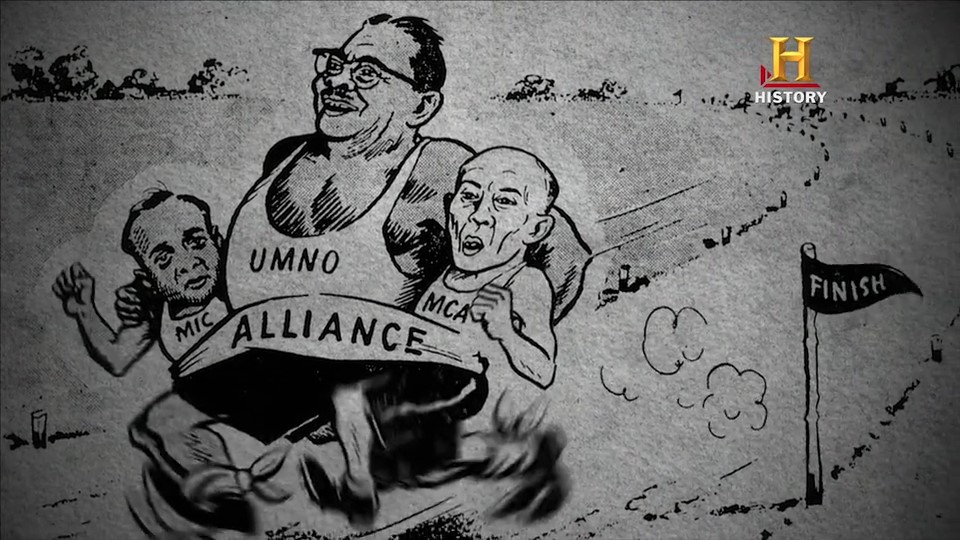

The UMNO-MCA Alliance would come out on top, winning 9 of the 12 seats being contested, while Onn Jaafar’s IMP only managed 2 seats at the municipal polls. Everyone from Tunku and Tan to the British who had been doubting the alliance at first were surprised at how well it did.

“It seems that the people were just not ready for a non-communal approach. That really kind of set the mould for race-based politics in Malaya,” – Zainah Anwar, author, as quoted in Road to Nationhood

As for Onn Jaafar and the IMP, the disappointing result at the polls would begin the end of Onn Jaafar’s political career. He would later dissolve the IMP and form the Parti Negara but it too would struggle to challenge the alliance.

And the same alliance eventually led to Malayan independence

That election was the first proof of concept. The Malayan Indian Congress (MIC) – who had been with the IMP during the KL elections – joined with UMNO and MCA after the election. The British, already considering granting independence to Malaya, were determined to see evidence of racial unity, and this was the model that seemed to work. The Alliance would go on to win the first federal elections in 1955, and also be crucial in the Merdeka talks with the British in the lead up to 31st August 1957. They would also of course dominate local politics for decades, until their loss in the recent GE14.

Back to modern times, it’s interesting to note how 60 years can change relationships, parties, and arguably the whole country. Looking back, you can see how far, how complicated and ultimately how successful Malay-Chinese relations were, and it makes you wonder what could happen if there was indeed a raceless version of Malaysia. But if there’s one new discovery that we made with this amazing documentary…

You can’t say we didn’t try it before.

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn3

- Email2

- WhatsApp33