Malaya’s Mulan: How this Penang girl pretended to be a man to fight the Japanese in WWII

- 8.8KShares

- Facebook8.6K

- Twitter15

- LinkedIn21

- Email27

- WhatsApp144

If you’re a Disney fan, you were probably one of those people who leaped at the first chance to buy a ticket to watch the live-action Mulan on the big screen. Regardless of your feelings about the live-action film, it’s safe to say that Mulan serves as a cultural icon, especially for Chinese girls who just wanna go out there and save China contribute to the society.

The thing is, though, there are actually speculations that Mulan wasn’t actually a real person. In fact, the legend of Mulan was mainly repackaged from a number of ancient texts, and there’s apparently no strong evidence to indicate that Mulan actually existed. But still, we’re sure that’s not gonna deter y’all from belting out the lyrics to Reflection every time it comes on.

Wait, wait, but what if we tell you that while Mulan may not have existed, there was a time when British Malaya may have produced our very own Mulan? Huh, how did that happen? Well, it all started when…

A group of Malayan Chinese volunteered themselves to fight a war

Without needing to actively read up on Chinese history, it’s likely that you already know about the Sino-Japanese War during World War II, where the Japanese allegedly orchestrated a number of horrifying war crimes against the Chinese. Some of the things they’d done included mass executions, mass rape, and inhumane torture.

“I will never forget the violence, the atrocities and the aggression that the Imperial Japanese soldiers enacted during the Nanjing Massacre.” – Survivor Chen Jiashou, as quoted from Facing History

During those days, the Chinese community in British Malaya wasn’t exactly sitting on their hands doing nothing either. See, when the situation in the war didn’t seem to be getting any better, the Chinese here wanted to do something, starting with fundraising.

In 1937, there was this Singaporean businessman who apparently had connections with British Malaya administration, Tan Kah Kee, decided to help out with China’s war efforts by setting up something called the China Relief Fund in 1937, and he even managed to raise around SGD$10million to support China. Eventually, the Chinese from places like Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, and, of course, Malaysia, joined forces with Tan and formed the Nanyang Federation of the China Relief Fund. In case you didn’t know. ‘Nanyang’ is basically the Mandarin translation of Southeast Asia.

“He felt very strongly about supporting not just the motherland, but the entire Chinese race with its 5,000-year-old history.” – Tan’s granddaughter Peggy Tan, as quoted from XinhuaNet

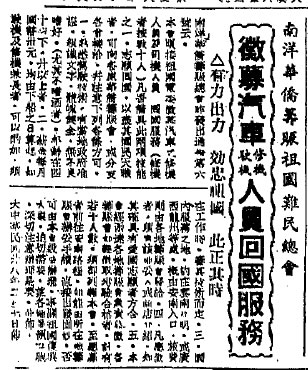

But then things in China got worse, particularly when the Japanese had blockaded all of China’s ports, meaning people had no way of getting in or out of the country via sea. To alleviate that particular issue, the Chinese government built a road connecting Yunnan to Burma in 1939, and sent a request to Tan for skilled drivers and mechanics from British Malaya to help them transport war supplies.

“It was a very dangerous road. It was not paved and not wide enough for two vehicles to pass each other. The drivers needed to have very good skills.” – A Nanyang volunteer Tan Chong Tee, as quoted from The Star

Within a month of calling for volunteers, a whopping 3,000 people across British Malaya volunteered for the job and were sent to essentially become soldiers for mainland China. They were called ‘Nanqiao ji gong‘, or Nanyang Volunteers, and their job was basically to transport fuel, weapons, ammunition, and soldiers to all parts of China.

And one of them was a woman who sneaked into the ranks

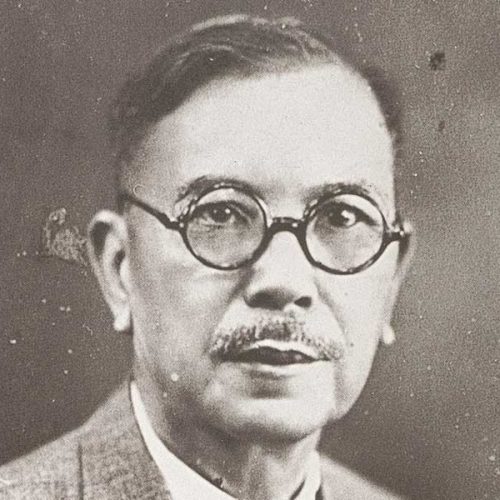

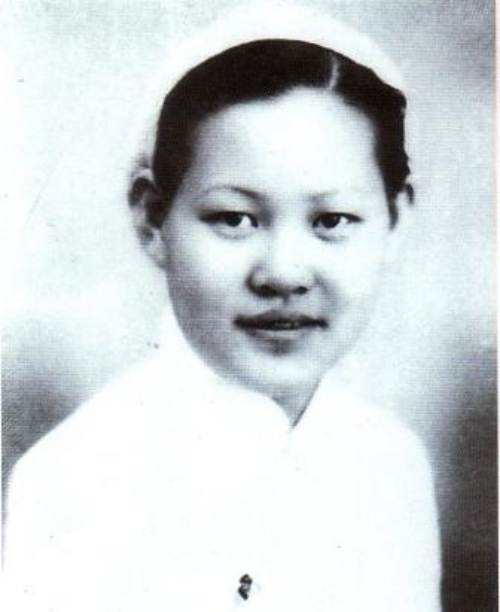

This was where our very own Mulan came into the picture. See, during a time of war and volunteerism, things can be a bit messy, making it a little easier for a Malayan Chinese lady to sneak into the ranks – and she was Li Yue Mei.

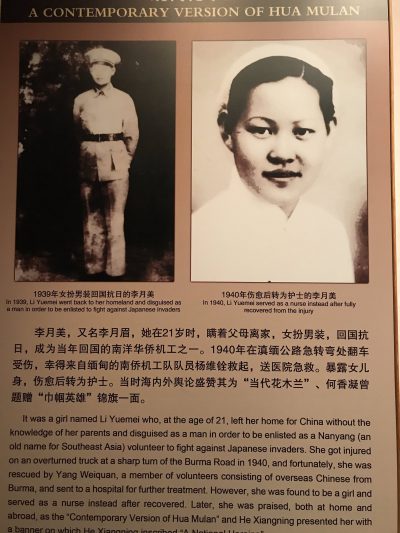

Hailing from Penang, she was said to have come from a rather well-to-do Chinese family. However, when the China Relief Fund began recruiting for volunteers to transport war supply to China, Li managed to sneak onto base by dressing up in her brother’s clothing and using a man’s name Li Dan Ying, much like Mulan did when she dressed up in her father’s armor and used a male name for herself.

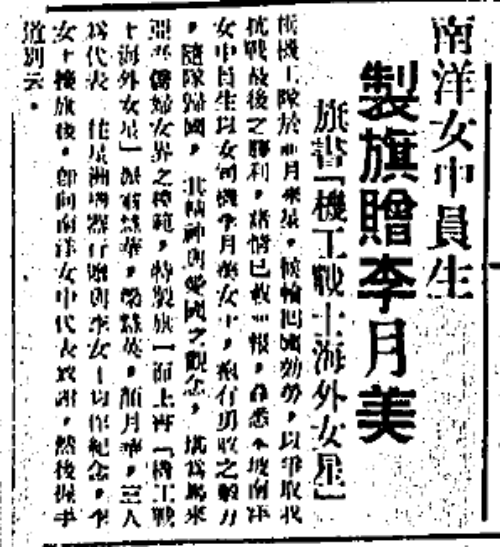

And, well, she succeeded. She had been one of four women to join Nanyang Volunteers. But unlike her comrades, who ended up becoming nurses or taking up other non-driving tasks, Li became a driver and mechanic, much like her male comrades, and drove alongside them to transport war supply in China. Apparently, even her brother had known that she was a driver, as he was a volunteer troop himself, but he didn’t disclose her identity to anyone at all.

However, while Mulan allegedly managed to hide her identity for a decade, Li’s driving career lasted only one year. She unfortunately encountered a car accident in 1940, and was saved by a fellow driver Yang Wei Quan. It was that very accident that revealed her identity as a woman.

Whelp, doesn’t this whole thing sound kinda familiar?

After coming out of the closet as a woman, Li returned to her ‘womanly’ roots after her recovery and contributed to the Nanyang Volunteers by becoming a nurse. In the process, she also fell in love with Yang, marrying him and returning home a hero in 1946.

Well, we suppose you can say Yang was the Li Shang to Li’s Mulan?

However, despite her marriage and safe return to Penang…

Unlike Disney’s Mulan, there was no happily ever after for Li

Despite the volunteers’ contribution to China’s war efforts against the Japanese, they couldn’t really stop the Japanese from trampling our own homeland, which many would later know as the Japanese Occupation of Malaya. You know, when the Japanese pretty much invaded Malaya on their fancy bicycles and drove out the British.

As such, Li and Yang chose to relocate to Burma. Together, they ran a coffee shop and had ten children together. While she was there, she even became a representative of the Chinese in Burma and met the then-Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai in 1954, who admired her bravery during the war and encouraged her to send her children to study in China.

But it was only in 1965 that Li apparently decided to follow Zhou’s advice – Yang disagreed with her moving abroad. That didn’t deter Li, because she went to Guangzhou with her children anyway, without her husband.

But when she moved to China, Mao Zedong was already the Chairman of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and he kickstarted this little thing called the Cultural Revolution in 1966. It was a ten-year long sociopolitical movement that was meant to preserve Chinese communism while getting rid of any capitalist or traditional elements that can threaten it. However, some claimed that the movement was a way for Mao to assert his control and destroy his enemies.

In that time, we can only say that a lot of bad things happened. The economy in China was devastated. People were getting hungrier and hungrier. And the country was basically living in fear because Mao had mobilized the young people to form paramilitary groups called the Red Guards to basically terrorize and persecute the elderly and those who are deemed to have capitalist ties.

And unfortunately, Li was a victim of the Red Guards. She was accused of having capitalist connections due to her businessman father and was looked down upon for having served as a Nanyang volunteer. She and her children were sent to the countryside for ‘reform‘, where she was harassed and sometimes even physically assaulted by the Red Guards.

The treatment Li received in China might have proven to be too much, because in 1968, she ended her own life. She didn’t get much peace post-death either, as the Red Guards forbade her children from grieving her and buried her body in an unmarked grave. For quite some time, Li’s name was forgotten. But thankfully…

Li was eventually declared a war hero in 1979

By then, the Cultural Revolution in China was over and Mao was replaced by Deng Xiaoping, who invalidated the Cultural Revolution and apparently was scrambling to fix Mao’s mistakes. It was only then they finally recognized the contributions of the Nanyang Volunteers and also Li Yue Mei.

In 1989, the Chinese government built a Memorial Monument in Kunming. There’s another Memorial Monument built in Wanding in 2005, equipped with a memorial hall to commemorate the Nanyang Volunteers who came from all the way from British Malaya to help in the resistance against Japan.

And in this memorial hall, there’s a plaque dedicated to Li, calling her a ‘Contemporary Version of Hua Mulan‘.

Meanwhile, in the Malaysia today, several monuments have been erected in memory of the Nanyang Volunteers, and they can be found in Penang, Selangor, Johor, and Sarawak. All in all, it’s said that of all those who joined the Nanyang Volunteers, only half managed to come back.

It is pretty inspiring to know that, in a time where women were prone to making meals in the kitchen, she was brave enough to disguise herself as a man and risk her life to join the Nanyang Volunteers. The least we can do now is to remember her actions as a war hero – our very own Mulan.

- 8.8KShares

- Facebook8.6K

- Twitter15

- LinkedIn21

- Email27

- WhatsApp144