Surprising downsides if Batu Caves gets the UNESCO World Heritage status

- 445Shares

- Facebook378

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn15

- Email15

- WhatsApp23

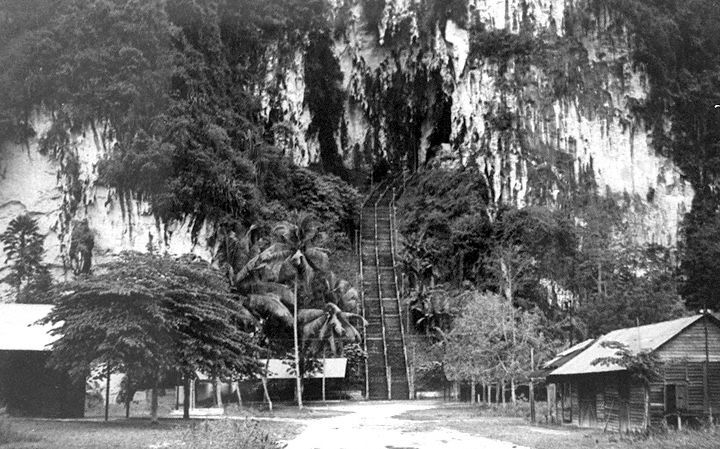

While the prettiness of Batu Caves’ new unicorn paint job is the talk of the town, the Batu Caves temple committee got themselves into a little trouble with the National Heritage Department (JWN) over the lack of permission sought for the upgrades made in conjunction with the former’s temple renewal process.

Yeah, JWN did say that Batu Caves is risking itself of being delisted as a national heritage status. But guess what Tan Sri R. Nadarajah, Batu Caves Sri Mahamariamman Temple Devasthanam committee chairman, said in response to this?

“The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has [already] deemed Batu Caves unfit for their heritage list. We do not need the [national] heritage status.” – Nadarajah told The Star.

Looks like UNESCO’s criteria for selection as a World Heritage site is one of the cited reasons for Batu Caves’s temple committee not caring about whether Batu Caves is a national heritage site or not. But then, we wonder…

What does having heritage status actually get you?

Before we jump into what the heritage status is for, it’s important to know that the World Heritage and National Heritage designations are different. The World Heritage Site is a designation given by UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention (WHC) while Malaysia’s National Heritage Site is given by the Commissioner of Heritage appointed by the Minister in charge of heritage.

“UNESCO seeks to encourage the identification, protection and preservation of cultural and natural heritage around the world considered to be of outstanding value to humanity.” – UNESCO’s objective of its WHC.

For obvious reasons, UNESCO’s WHC is basically about conserving something so precious to the world through several ways like signing the convention, making management plans and reporting systems, giving assistance and training, supporting awareness campaigns and fostering international teamwork.

And having a huge reputable global organisation like UNESCO tell us that we have something with “outstanding universal value” is just too good to turn down. If it’s not this pride that benefits us, it might be the extra media attention and boost in the country’s tourism.

If enough tourism revenue is collected and publicity about an endangered site reaches as many donors as possible, then these funds can be collected to pay for conservation efforts. One such site was the ancient Buddha statues in the Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan, which were blown up by the Taliban in 2001.

Over here in Malaysia, the national heritage sites are subjected to the rules in the National Heritage Act, unlike the world heritage sites that are subjected to the WHC. Our National Heritage Council (NHC), under JWN, is like an advisor to the Minister and Commissioner for any decision related to heritage sites.

The Commissioner’s role involves working with the owner, local planning authority and Minister. The Commissioner talks to the owner about inspections, buying/leasing and removals. The Commissioner also advises the local planning authority before giving them permission to do any development and works with them after that to make sure that they follow the rules.

To ensure that the areas surrounding the heritage site are protected, the Minister determines the buffer zone around the heritage site. And to ensure that everyone knows what to do, a management plan is made by the Commissioner for promoting the protection of a heritage site, ensuring the proper management of the heritage site and promoting educational programmes or financial help to the owners. The heritage fund is thus used for financing these efforts.

What about the owner’s part in this? Well, when the site is designated, the ownership remains the same except for inheritance or approved sales. Since the site still belongs to the same owner, it’s actually the owner’s duty to maintain the site. But if the owner does not fulfill his duty, then the Commissioner will.

The owner also has to apply to the Commissioner if they need a loan to fund their conservation work. The owner can charge an entry fee into the heritage site and if the commissioner contributed to the conservation funding, then the commissioner may impose a levy on the entrance fee lor.

While the Act states that the Commissioner has the power to give national heritage designations, we still couldn’t find any sign of the Commissioner’s power to rampas the designation of a site itself (but funnily, got say about de-heritaging adjacent sites if the site itself is de-heritaged under Section 25). So, technically, it’s illegal for a national heritage site including Batu Caves to have its designation revoked unless the Act is amended (CILISOS wrote about this).

If like that, then Malaysia should nominate Batu Caves for designation to conserve it, right?

Let’s see if Batu Caves passes the qualifying round

Here’s a simplified list of criteria:

- Awesome work of art

- Interchange of human values

- Unique cultural practice or civilisation (existing or gone)

- Major historical events

- Traditional settlement (human interaction with land or sea)

- Related to events, traditions, ideas, beliefs or artistic and literary works. This one’s usually used with other criteria

- Natural beauty

- Huge changes in earth’s landforms

- Ongoing ecological and biological processes in ecosystems

- Protecting biodiversity

UNESCO also considers the protection, management, authenticity and integrity of the sites.

So, does Batu Caves have what it takes? Well, we came across a blog post that says yes. Blogger NK Khoo argued that Batu Caves meets 3 of UNESCO’s criteria (iii, vi and x), due to its Temple Cave being the main venue for Thaipusam and its Dark Cave being home to various species of bats and spiders.

But the relevant parties beg to differ. A JWN spokesman said in 2013 that Batu Caves lost its appeal and that some of the structures do not blend in with the environment, so it doesn’t qualify for the UNESCO designation lor. It’s been suggested that the local authority has not been making sure that the temple committee follows the conservation requirements.

International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Malaysia chairman Datuk Hajeedar Majid said in 2015 that Batu Caves would have qualified for the World Heritage list at least 50 years ago. But now kenot.

“Today, the developments around it such as the commercial complex, the shops, the entire physical space and the environment and historical buildings such as the grand staircase leading up to the cave temple are not in harmony with the entire site,” – Hajeedar explained.

But the former minister of Tourism and Culture Nazri Aziz said that Batu Caves could still qualify as a national heritage site (and it did) because of its unique combo of cultural and natural elements in the area, which need to be protected. But even if a site is not given the national heritage status, the JWN can still be consulted on the best conservation practices.

But having heritage status may have disadvantages. What?!

Yeah. Another cited reason Nadarajah said for not needing national heritage status is that Batu Caves didn’t benefit from it. According to him, it turns out that the JWN did not give any grant to maintain the site.

But worse than this is that being a UNESCO World Heritage site may be more like a curse than a blessing. As we said earlier, the designation brings more publicity and tourists which can be good. But it has a negative side too. Since more people know about a particular site, more people would want to visit it.

Two of our World Heritage site cities Melaka and Penang are witnessing the damages resultant from the surge in tourism. Uncontrolled tourism and gentrification in Melaka is messing up what made Melaka special in the first place.

“Before the inception of Unesco World Heritage, our town was rustic and unpretentious, full of unique flavors, hybrid races, the smell of incense, wood houses, the muddy river, the sounds of craftsmen at work. But World Heritage status has changed Melaka from a quiet community to the monstrosity of tourist commercialism and business. Old traders have been replaced by fancy bars and hotels. We have cartoon heritage, monstrous mega-projects, Hello Kitty buildings.” – said Bert Tan, head of the local Malaysian History and Heritage Club, and a resident of Melaka.

Having too many tourists in one place also affects the locals. According to a travel blog Tripologist, the locals of the host country drop their traditional lifestyle and hop onto the tourism business to accommodate to the higher demand.

And imagine a bunch of strangers coming into your home and invading your private space. That’s what’s happening to the residents of Penang‘s Clan Jetties. Not everyone is fine with losing their right to privacy when their own homes have been treated like a museum (or zoo) by uninvited visitors. Because of this, some of the residents have moved out.

“I would like to remind people that we are not monkeys, and this is not a zoo.” – a Clan Jetties resident told the South China Morning Post.

At this point, you may be wondering if UNESCO can do anything about these issues. Most of the time, UNESCO’s legal role is limited. It can advice on conservation practices, label endangered sites as “in danger” or de-heritage a site, but it cannot force the local authorities to obey certain practices, which means that JWN is free (at least, from UNESCO’s authority) to decide on the regulation and maintenance of the sites.

- 445Shares

- Facebook378

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn15

- Email15

- WhatsApp23