For the first time in history, Malaysian heritage buildings are going to be ‘de-heritaged’

- 21.2KShares

- Facebook20.3K

- Twitter110

- LinkedIn7

- Email219

- WhatsApp495

If you’ve ever been to A Famosa or Dataran Merdeka, or driven through KL and seen this building…

… or even this one…

… you would have wondered what the stories behind these buildings were. When were they built? Who built them? What are they being used for now? And who takes care of these buildings?

These buildings are known as heritage buildings, which means they are important because of their history or the way they look. The two beautiful buildings above were placed on the heritage list set into law by the National Heritage Act in 2005 to protect them from being destroyed or damaged.

But… there’s a problem.

You’d think that “heritaging” a building would be powerful or protective, but the government is revoking the heritage statuses of two other beautiful heritage buildings – Malaysian Tourism Centre (MaTiC) and Dewan Tunku Abdul Rahman – on Jalan Ampang, KL. And if this happens, the Bok House destruction in 2006 could happen again.

If you aren’t familiar with the Bok House incident, back then, conservationists had tried to get a large mansion called Bok House heritaged soon after the National Heritage Act passed. The mansion had been built in the 1920s by a famous businessman at the time and had a rich history of its own. But by the time they tried to get the Bok House registered, it was too late and the building was destroyed.

So today, we could be seeing history repeating itself with the de-heritaging of the MaTiC and Dewan Tunku Abdul Rahman buildings. But… what are the significances of these buildings? And why are their heritage statuses being removed?!

Introducing, the building being “de-heritaged”

So the MaTiC Building and Dewan Tunku Abdul Rahman are actually the same thing, because the Dewan is a part of the MaTiC Building. What is historically significant about this hall is that it was where Tuanku Abdul Rahman of Negeri Sembilan was installed as Malaysia’s very first Agong in 1957 and where Parliament had its very first meeting in 1959.

The original building was built as a family home in 1935 by Eu Tong Sen who was one of the biggest businessmen in Malaya at that time. The home was built on 2.6 hectares of land that was previously a rambutan orchard. During World War II, the British took over the home and used it as their military base until the Japanese came over and kicked them out of the building to have it for themselves. Eventually after the war ended in 1945, the British came back for the building and made it their garrison camp until 1956.

After Malaysia received its independence, the building was used as the military HQ of our new country as well as the National Art Gallery until 1988, when the Ministry of Arts, Culture and Tourism took over the building, renovated it and made it the Malaysia Tourist Information Complex. 28 years later, because of its architecture and historical significance, the building was gazetted as a heritage site (or “heritaged”) on 16 June 2016 under the National Heritage Act.

Now, you’d think that heritaging a building would mean that the building remains protected for as long as possible, but less than half a year later, its heritage status is now being revoked.

In exercise of the powers conferred by paragraph 31(2)(a) of the National Heritage Act 2005 [Act 645], the Commissioner revokes the designation of the sites specified in the Schedule as heritage site as published in the Notice of Designation of Site as Heritage Site on 16 June 2016 – Statement by Dr. Zainah Binti Ibrahim, Commissioner of Heritage, National Heritage Department

From this statement issued by Jabatan Warisan, three sites of the building are being de-heritaged: Lot 45 which is the car park of the tourism centre, Lot 158 which is a five-storey building where the KL Tourism Office is, and Lot 139 where the Eu Tong Sen house and the Dewan Tunku Abdul Rahman are.

So why exactly are Jabatan Warisan trying to revoke the heritage statuses of these sites?

The issue isn’t the revoking – it’s how they’re revoking it

To be fair, Tourism and Culture Minister Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz clarified that they only want to revoke parts of the area around the building to allow for planning of a new development, including installing a hotel. While there are some who agree that the building should be de-heritaged, the problem isn’t revoking the heritage status of this site exactly – its the fact that nowhere in the law does it say that they can revoke the heritage status of a site under the National Heritage Act.

So there are three issues here – one is that Jabatan Warisan might be breaking the law, two is the fact that if you can de-heritage a building, why bother heritaging at all? and three, what Jabatan Warisan wants to do is against United Nations guidelines on this issue.

Now, the first issue is since the law doesn’t actually allow de-heritaging, this means that if the Jabatan wants to revoke the heritage status of the building, they would have to amend the law to allow them to do so. And if they don’t, they would have to do it anyway potentially in violation of the law. This could end up being decided in court, as there is disagreement on whether or not this is illegal.

The second is that even if the law did allow this, the question is whether it should. In a statement issued by the Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia, they make the point that if Jabatan Warisan manages to make the u-turn on the MaTiC building’s heritage status, it shows that the law doesn’t protect heritage properties as well as it should. Because what’s the point of putting a property on the “protected list” if it can just as easily be taken off?

The third issue with this whole thing is, even if they are just planning on developing the area around the building, why would they revoke the heritage status of the building itself (Lot 139)? In the United Nation’s Guidelines For How To Jaga Heritage Properties around the world, its section on “Buffer Zones” say that there should be an area surrounding the protected property which also has restricted permissions for use and development. This is so that there is another “layer” of protection around the piece of property or building that’s heritaged.

Now, to explore the problems and details of each of these three issues, we need to look into what exactly the law says to know what it allows and doesn’t allow.

Does Malaysian law actually matter for protecting heritage buildings?

So as it is right now, Malaysia’s laws aren’t actually that bad compared to other countries. In UK, the person in charge of heritaging buildings can actually remove the protection given to a building if they wanted to. In Singapore, authorities can still tear down a building even if it has been given status as a conserved structure.

But according to our laws, there is no explicit permission that allows for revocation of heritage buildings. What our law actually does say is that objects (for example, a keris or a crown) that have been heritaged can be de-heritaged. The difference between objects and buildings is important because imagine if your mom gave you permission to take a snack from the fridge, and when she said “snack“, she only meant “apple” or “orange“. And then you go pandai-pandai take a cornetto even though that’s not what she meant.

There is another section of the act where it implies that the status of heritage sites can be revoked, which again is different from the explicit permission like in UK and Singaporean laws. The law mentions that the area surrounding a heritage site can also be heritaged, for example, to make sure that no one builds a nightclub next to A Famosa. But after that, the act says that the surrounding area can be de-heritaged if the main site is revoked.

So while the law indirectly implies that heritaged sites can be de-heritaged, it shouldn’t be good enough because it still doesn’t give this permission explicitly. When Jabatan Warisan released its notice revoking the heritage status of the MaTiC building, it mentioned a part of the law which only talks about giving a site heritage status and not about revoking it. So even if there is an implication that the law allows de-heritaging, Jabatan Warisan did not cite that part, which means they will need to amend the law accordingly for it to be said explicitly.

Unless the Act is amended to enable (de-heritaging the building), it is questionable if the commissioner has the power to revoke a heritage site which has already been gazetted and if that is so, this revocation is ultra vires the Act – Elizabeth Cardosa, President of Badan Warisan.

Well, so should the law be changed to allow for de-heritaging?

That’s the point here. According to Elizabeth Cardosa who is the president for the guard dog of heritage sites here in Malaysia, Badan Warisan, the issue isn’t de-heritaging exactly. It’s making sure that if Jabatan Warisan wants to de-heritage this building, they have to do it properly. And so if they do it properly, they need to make sure that what they do to the building doesn’t rosakkan it.

Change has to be managed, change has to be reasonable, and it has to not compromise the authenticity and heritage value of a place. – Elizabeth Cardosa, President of Badan Warisan, in an interview with BFM Radio.

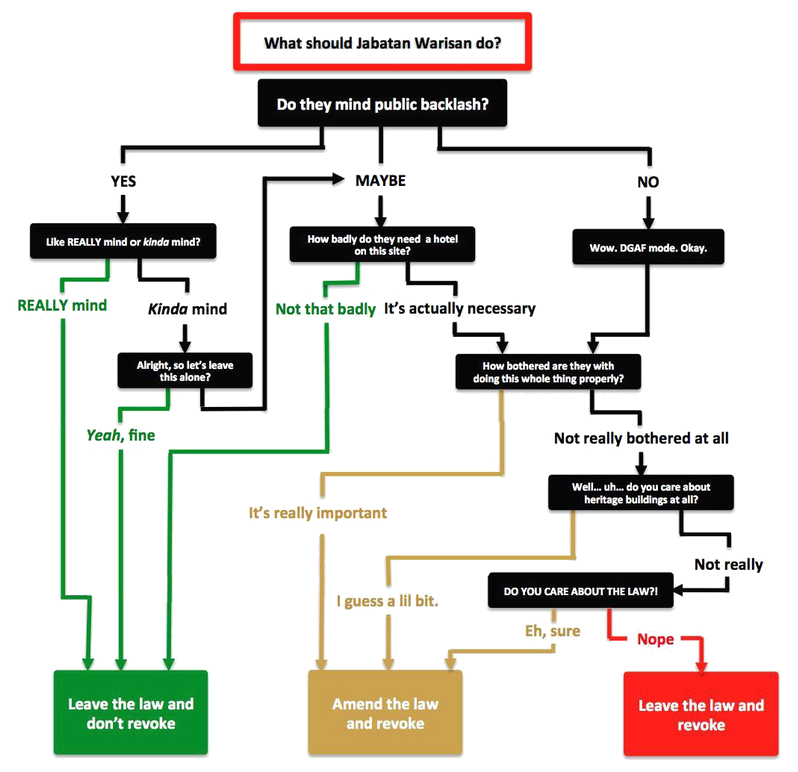

So according to Badan Warisan, if Jabatan Warisan doesn’t amend the law to do what they said they wanted to do, they would pretty much be acting against the law. Now the question is whether or not the law should be changed to let them do what they said. And to help you understand this, here’s a handy flowchart to run you through Jabatan Warisan’s options!

Green here means they don’t amend the law and they don’t kacau the heritage status of the MaTiC building. Yellow means they do amend the law to revoke the heritage status of the MaTiC building because this would be the proper thing for them to do. But it would now mean that other heritage buildings can potentially be destroyed if the Jabatan thinks it should be.

The absolute worst case scenario would be RED, which is what happened to Bok House, and which is what could happen to the MaTiC building if Jabatan Warisan doesn’t care about the law and doesn’t care about taking care of the heritage buildings in Malaysia.

Right now, we still have to wait for Jabatan Warisan to issue another statement on what happens next. So far only two organisations have spoken out, which were Badan Warisan and Pertubuhan Arkitek Malaysia. When we tried calling the Jabatan for questions, no one picked up and when we tried to visit their office on a weekday, the place was empty. But until we hear more, what do ugaiz think? Should the law be changed? Or should heritage buildings be protected forever?

- 21.2KShares

- Facebook20.3K

- Twitter110

- LinkedIn7

- Email219

- WhatsApp495