3 Iban folk stories kept alive thanks to Benedict Sandin, Sarawak’s greatest historian

- 3.2KShares

- Facebook3.1K

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn5

- Email14

- WhatsApp44

Ok, quick question for all the non-East Malaysians: off the top of your head, how many traditional Iban folk tales can you name?

Well, if your answer was none, don’t worry – we couldn’t name any either. Fortunately for us, we were able to quickly find and read up on those stories in English. Fortunately for you, we’re giving you the abridged version of three of the most famous Iban/Dayak folk legends to impress your friends with.

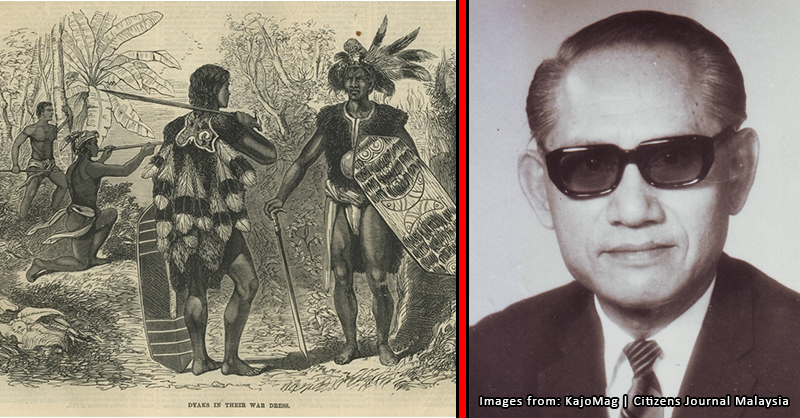

And this is all thanks to a Sarawakian historian named Benedict Sandin.

But before we dive into those stories, let’s first take a look at the man who curated them, and why he was so important to the overall history of Sarawak and Iban/Dayak culture.

(Note: ‘Dayak’ is a blanket term used to describe more than 450 ethnolinguistic groups living in Borneo; not all Dayaks are Ibans. However, these groups generally share similarities in terms of language, lifestyle, and customs)

Benedict Sandin was born into a prominent Iban family

The grandson of the Native Chief of Lower Paku Iban, Benedict (birth name Sandin Anak Attat) was born in 1918 in a longhouse in Saratok, Sarawak. Sandin was taught the poetic Iban language by his father (an Iban public orator), and grew to love it.

Eventually, he became a junior Native Officer for the Raj of Sarawak in 1941. After the Japanese occupation ended, he was transferred to the Education Department, and later became an Information Officer for the Sarawak Information Office.

However, his big break would arrive during his stint as editor for the first Iban language news publication. Recognizing Sandin’s writing talent, Tom Harrisson, the then-curator of the Sarawak Museum invited him to join the museum staff in 1952. Sandin kept himself busy for the next 14 years before taking over the curator role from Tom Harrison, publishing his magnum opus ‘The Sea Dayaks of Borneo before White Rajah Rule’ the year after that, in 1967.

HE was among the first (if not the first) to collect and document Iban oral history and genealogy, which is a pretty big deal since the problem with anything oral is that they won’t last long – becoming lost or forgotten over the generations.

So as promised, here are 3 (very shortened) stories made possible thanks to Benedict Sandin.

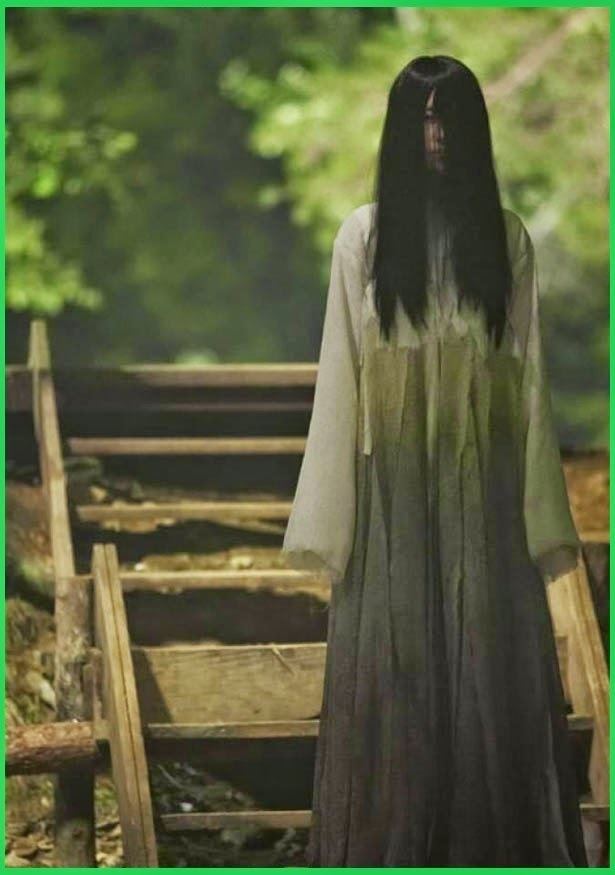

1) Kok-lir, the female ghost who… rips off men’s testicles?!

Sorry to start off the series with such a gruesome mental image. But yeah, ghost story time.

As it turns out, native Borneans had their own name for the bloodthirsty female vampire-thing we call a Pontianak: kok-lir. In fact, so great was the impact of this ghost that it is alleged that the city of Pontianak, Borneo (part of Indonesia) got its name from her.

And how could it not, seeing as it literally rips off, err, koks.

The kok-lir is similar to what we know of conventional Pontianaks, although there are some variations:

“The indigenous people of Borneo believe that every unfortunate woman who dies in child-birth, inevitably is converted into the kok-lir. At this sort of death, before any antidote can be applied, the deceased’s nails have already been rapidly growing very sharp and long. The traditional way to prevent this from happening is to prick the soles of the deceased’s feet with thorns of a citrus tree.” – Benedict Sandin, Ghost Story, The Sarawak Gazette, September 30, 1964

Sandin continues his piece with an account of two of the victims of the kok-lir. The story goes that a widower and his son who had just done fishing for the day, took shelter in a hut owned by two beautiful women. The two women treated them with the utmost hospitality, even cooking meals for them.

However, as the widower’s son sat naked on the floor , one of the women pointed at his testicles, yelling “Haii-waii-wai! It’s the sweet stuff!”, and her nails immediately started to grow longer. Fearing for their lives, the widower took his son and dashed to his boat, all the while being chased by the two women who were screaming “kok-kok-kok” (we swear we aren’t making this up).

In desperation, the widower overturned their boat to hide underneath, and the two women jumped on top of it, boring into the hull with their nails. However, before they could get to their prey, the sun rose, and the two women disappeared. Although suffering badly from cold and shock, the two men ultimately lived to fish another day.

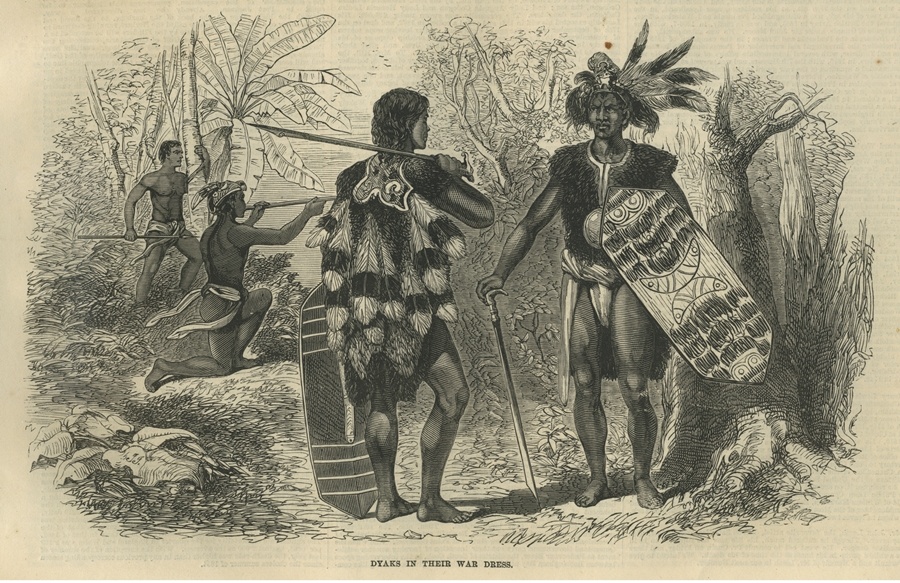

2) Aki Lang Sengalang Burong, the Iban God of War and Omens

Here’s a war story highlighting the importance of omens in Iban culture. But first, some mythological background:

The most important figure in Iban religion, Aki Lang Sengalang Burong – the ‘King of Birds’, also known as ‘the earth tremor which trembles and causes the full moon to fall’ – is believed to be the ancestor of the Iban people.

Being the strongest of the Petara (deities), Sengalang Burong was placed in charge of all war-related activities of the Iban people, and possesses amulets of war, or pengaroh, to combat foes. Sengalang Burong is also the god of omens and augury (interpreting omens from the behavior of birds), with these omens delivered via seven ‘omen birds’ who are said to be Sengalang Burong’s son-in-laws.

Once upon a time, Sengalang Burong took his sons and grandson Sera Gunting on a war expedition in order to teach Sera the proper omen procedure in warfare. He gave his grandson his best war charms and fabled ‘nyabor’ sword – a sword so powerful no one who used it “has failed to obtain an enemy head”.

Shortly after setting off, one of Sera Gunting’s uncles stepped off to the right side of the path, laughed, and returned. As it turns out, this simple act was in fact an omen called sandik belantan chawit, signifying that the enemy will be struck by a sword from the left to right of the body.

For the next five days, they continued their march, observing various rituals that came in a ‘set’, intended to keep them safe and give them various advantages in battle. The last two in the ‘set’ of omens were performed by Sera’s uncles; weeping to signify the ‘weeping cry of the enemies over their dead warriors’, and coughing off the left side of the path to satisfy the ritual of madam ka suloh mata munsoh, or, ‘switching off the vision of the enemy’.

When they finally arrived at the enemy longhouse, they waited and attacked at dawn while most of their enemies were still sleeping. Following their victory, they looted the place and went home. Sengalang Burong then told Sera he had taught him all he needed to know about warfare omens.

It’s a super long read leading up to an anti-climax, but that’s kind of the point. As you can see, this was a war story that focused on the omens rather than the actual fighting, signifying that omens are very, very important in Iban culture. In fact, an Iban’s entire lifestyle is centered around these omens, which provide guidance for situations such as warfare, headhunting, farming, and even building a new longhouse. Because, according to the advice of Sengalang Burong:

“If you never listen to the call of omen birds, no amount of charms will make your work prosper.” – Professor Clifford Sather and Benedict Sandin, The Sarawak Museum Journal Vol. XLVI No. 67, Dec. 1994

It’s no wonder then, that the Gawai Burong (a nine-stage festival honoring Sengalang Burong) was once the most important festival among the Iban community.

(You can read up on all of this and more in Benedict Sandin’s 1962 book Sengalang Burong)

3) Unggang and the goddesses of Mount Santubong

A real mountain in Sarawak, Mount Santubong is a place steeped in Iban mystical beliefs. Once the location of a booming trading port dating back to the 7th century, Santubong derives its name from the Iban ‘Si-antu-ubong’, meaning ‘spirit boat’, which is symbolic of the coffins said to act as ‘boats’ to ferry the dead into the next life.

According to Benedict Sandin, Mount Santubong is believed to be the place where Ibans first built wooden coffins for their dead, as the deity Raja Jembu (father of Sengalang Burong) is said to have built a wooden coffin for his father Raja Durong here.

Mount Santubong is also said to be the residence of two beautiful goddesses by the names of Bunsu Kumang and Bunsu Lulong.

The story goes that once, a very powerful Saribas Dayak war leader named Unggang Lebor Menoa had a dream about these two women. In it, he encounters them on Mount Santubong after their bath and receives one of their bathing stones, called ‘Batu Perunsut’. They told him that this stone was a charm that gave him invincibility in battle, but warned that its protection only extended to the southeastern-most border of Santubong.

After the dream, Unggang built a large war-boat, using it to defeat the Bajau and Illanun pirates who tried to invade via the mouth of the Saribas river, as well as to kill strangers who dared sail those seas.

After Unggang’s death, his son Luta succeeded him as chief of the Saribas Dayaks. Upon his succession, Luta’s tribe entered into a conflict with their Undop, Balau, and Sibuyau Dayak neighbors. Many bitter battles were fought, but Luta and his allies eventually launched full-scale invasions on Sibuyau and Undop territory, slaughtering many.

Luta’s next goal was to sail to the island of Belitong near Sumatra to buy a tuchong (shell armlet) for his inheritance. He took his two brothers and set sail…. only to never return. The only news received was that a piece of their boat had washed up at the mouth of Sungai Ubah, miles off the southeastern border of Santubong.

These stories may not have been told, if not for Benedict Sandin

It’s usually a challenge for us to research indigenous cultures, but we were pleasantly surprised at the relative ease which we were able to access detailed information on Iban/Dayak culture. And most of those sources tended to lead back to one name: Benedict Sandin.

After his retirement, Sandin became a Senior Fellow at USM Penang before returning to his hometown in Paku where he, yep, you guessed it – continued researching Iban culture. Although Benedict Sandin died of lung cancer in 1982, his legacy will forever live on in every retelling of the stories and histories of the Iban people.

It’s only fitting then, that on his 102nd birthday last year, Google acknowledged his contributions to history with a cute little Google Doodle of the man doing what he loved: curating Iban history.

- 3.2KShares

- Facebook3.1K

- Twitter5

- LinkedIn5

- Email14

- WhatsApp44