Banana flavoring is said to be based on an extinct banana… which still exists in Malaysia

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn7

- Email10

- WhatsApp11

If you’ve ever went through a baking phase – either during the MCO, or just near festive seasons – you might have went shopping for ingredients and saw these tiny bottles of artificial banana flavor.

Normal, everyday people probably would see one of these as just another bottle of artificial flavoring, but those who’re bananas about bananas would know that there’s an interesting story regarding this exact flavoring. In the US, where banana-flavored candies are quite common, people noticed that banana flavoring tasted quite different from a real banana – too sweet, and kind of articial. However, as some had theorized, it be like that because it was based a different banana that went ‘extinct’ about a century ago.

Before we start blaming Big Banana for this, it’s not that much of a conspiracy, but a rather tragic kind of story. The bananas spoken of in legends didn’t so much go ‘extinct’, but more like ‘went out of circulation’. It was called the Gros Michel, and apparently…

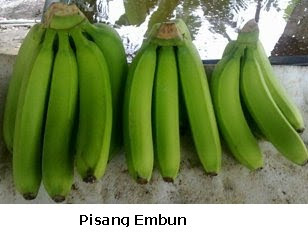

You can still find it in Malaysia under the name of Pisang Embun

At least, that’s what everything we found pointed to, anyways. There are literally more than a thousand different kinds of bananas in this world (called cultivars), and at least 100 different kinds are grown in Malaysia. One of these is apparently the Gros Michel, known locally as the Pisang Embun. It’s so rare in the US that angmohs would fly over here to get a taste. However, if you are to look at reports about our local banana industry, Pisang Embun seems to not be as commercialized here as the Cavendish or the Pisang Berangan. It’s also seemingly not very common in supermarkets.

So what’s so special about this pisang, and why did it become such a rare delicacy in the US? Well, for one thing, bananas weren’t really a naturally US thing, being a tropical plant. Most of it had to be imported from the Latin Americas. In the olden days, where everything travels by ship, not many bananas can survive the journey into other countries… until the Gros Michel came along. With its thicc skin and long time taken to get ripe, you can cut down a bunch of green Gros Michels from faraway plantations, dump them on a ship, and have them arrive in the US all yellow and ready to eat.

That was the US’s first encounter with the banana, and it became a big hit. Gros Michel plantations grew to keep up with the demand, but tragedy struck. Because a good banana is hard to get naturally, once a plant that makes a perfect banana comes along, planters will usually just grow new banana plants using parts of the perfect plant to make sure the new plants make the same kind of fruits. For example, all Gros Michel banana plants are clones of each other, which is why their fruit are almost always the same size, color, and taste. Very nice and uniform.

Unfortunately, that means that they all also have the same weakness to disease, so when a fungus called Fusarium oxysporum fs cubense comes along into a Gros Michel plantation, it’s basically a banana buffet for them. The fungus caused something called the Panama disease, which turned whole banana plantations into a blackened mush. Since it spreads through tainted soil, all it takes for it to spread is one dirty farmer walking to another plantation without washing his boots.

By the 1890s, Panama disease got so serious that Gros Michel plantations were dying out, but it’s not the end of the banana industry…

To replace the Gros Michel, the blander Cavendish variety was planted

After the Panama disease started, people started looking for a different kind of banana that could withstand the disease, but at the same time be as export-friendly as the Gros Michel. Their solution to this was the Cavendish banana. You might have heard of them kind already, since about 99% of all exported bananas are Cavendish ones. They looked almost similar, but the Cavendish was slightly more fragile than the Gros Michel, so exporters have to modify their packaging a bit when they made the switch.

But there’s another difference that’s of interest to this article: the taste. Apparently, the Cavendish is a bit less flavorful than the Gros Michel, but when the switch happened, people don’t seem to notice or care that much. According to author Dan Koeppel, who wrote a whole book about bananas and their history, the differerence is very slight, but both were nowhere near the best banana ever.

“The Gros Michel is a better tasting banana. I don’t think there’s any question about that. But it’s not a million miles ahead of Cavendish,” – Dan Koeppel, to Atlas Obscura.

There is still a difference, though, which is perhaps why some had said that banana flavoring, which gives off a sweeter, more ‘artificial’ taste, does not really taste like the bland Cavendish that people are used to now. This led to theories that the flavoring is based off of the lost Gros Michel, and according to Rob Guzman, a Hawaiian banana farmer who still grows banana species like the Gros Michel, the real thing does taste a bit like the flavoring.

“It’s [the Gros Michel] almost like what a Cavendish would taste like but sort of amplified, sweeter and, yeah, somehow artificial. Like how grape flavoured bubble-gum differs from an actual grape. When I first tasted it, it made me think of banana flavourings.” – Rob Guzman, to BBC News.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the flavorings were based off of the fruit itself. Banana flavorings mostly contain an ester called isoamyl acetate, a chemical that’s found in real bananas as well. Foods that use this flavoring appeared in the US for at least a decade before the actual fruit itself, so people have been making and using banana flavorings before the fruit became popular. Also, the taste of a real banana is more complex, involving several different chemicals at once, so it’s highly unlikely that the chemicals from a real banana is reverse-engineered to make the flavoring.

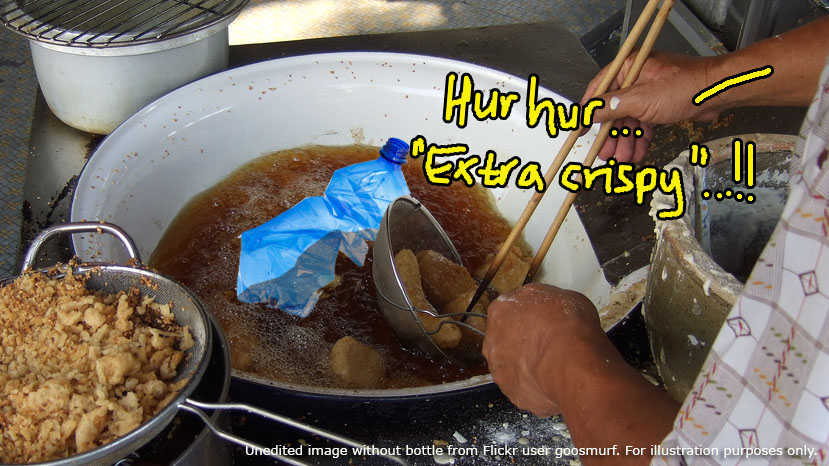

The reason why the flavoring tastes more like the Gros Michel aka Pisang Embun is simply because the variety has more isoamyl acetate than the Cavendish. So the banana flavoring wasn’t really based off of our Pisang Embun, but more from pisangs in general. Bummer. Still, it’s a fun story to tell the next time you’re eating pisang goreng with your friends. And if the pisang used is for that is Cavendish (ew), here’s something else to tell them…

The Cavendish might soon go away as well, but at least we have other bananas

Just like how the Gros Michel bananas were clones of one another, so is the the Cavendish. Which means that eventually, there will come a fungus or disease that will wipe out whole Cavendish plantations as well. Try as we might, we can’t help but think that the pisang will berbuah dua kali… which is ironic since a lot of the local news stories surrounding the pisang embun involves them berbuah-ing multiple times.

It’s inevitable, and according to Dan Koeppel from earlier,

“[Every] single banana scientist I spoke to—and that was quite a few—says it’s not an ‘if,’ it’s a ‘when,’ and 10 to 30 years. It only takes a single clump of contaminated dirt, literally, to get this thing rampaging across entire continents.” – Dan Koeppel, in an interview, quoted by Time Magazine.

Anyway, the pisang had berbuah dua kali already. In the past few decades, Cavendish plantations worldwide had been attacked by a more virulent form of the Panama disease, called Tropical Race 4 (TR4). TR4 had already reached Malaysia for some time already. In the 1990s, Malaysia was reported to have started several Cavendish plantations, but they were wiped out by the fungus strain.

Interestingly, though, when a survey was done on how much the fungus had spread in Johor’s banana plantations back in 2016, it was found that Cavendish, Berangan, Rastali, and Emas banana plantations were the most affected by the fungus, while plantations of Awak Abu, Masak Hijau, and Abu bananas were virtually untouched.

So basically, the moral of the story is planting a lot of different banana types locally will ensure that we’ll always have something to dip in batter and fry in the evenings, and even if all our bananas are gone… at least we’ll still have ubi or something.

- 1.1KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn7

- Email10

- WhatsApp11