Jerunai: The Melanau Burial Pole Involving Human Sacrifice

- 113Shares

- Facebook73

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn9

- Email7

- WhatsApp17

Graves are meant to be peaceful resting grounds for the deceased but did you know that hundreds of years ago in Sarawak, the Melanau ethnic group used to practice human sacrifices on slaves every time an aristocrat died? Back then, instead of just laying the dead to rest, they would also bind living slaves onto a pole called Jerunai, and their spirits would scream and roar years after they’ve died.

This ritual, however barbaric it may seem to us in present day, was actually very well-hidden and even forgotten by the Melanau people today. There are limited resources talking about the Jerunai, and this writer only found out about it through a Netflix film titled, Curse of The Totem. From there, we did some digging on the internet and discovered some pretty interesting historical facts.

So, let’s go back in time to learn about the Jerunai, a burial pole that was considered so cruel and deeply-entrenched that a white man arrived in Sarawak and went WTF?

Jerunai might be the most atas coffin in Malaysian history

Known in the past as a symbol of wealth, rank and sovereignty, the Jerunai is a burial pole made out of the wood from Belian trees, which are known to withstand extreme weather and torrential rain. Back then, the Melanau people praised the aristocrats and would pay their respects towards this group’s communal generosity by keeping their remains in these fancy coffins.

It is said that Jerunai would take more than 15 people to craft and up to 7 years to complete since these coffins were 12-15 metres tall and beheld intricate carvings. When a male aristocrat dies, the carvings would be of majestic animals like tigers and dragons to signify their power, but for female aristocrats, carvings of flowers and fruits would be done to signify femininity and fertility.

You may be wondering though, if the Jerunai took 7 years to complete, what happens if an aristocrat mati katak? What happens to their body then?

Well, the deceased aristocrat would be housed in a hanging coffin temporarily until their Jerunai was ready. Most of the time, the villagers would be alerted of an aristocrat who was dying and they would get to work ASAP. But even then, these aristocrats would die before their coffin was completed. To ease their pain, since doctors and Panadol Actifast weren’t around yet, bomohs would attempt to heal the sick.

Because of that, the Jerunai would not keep freshly dead corpses but the skeletons and remains of these dead aristocrats. So, you might be wondering why the Jerunai is a burial pole when we’re not really burying the aristocrats. Actually, the ritual buries innocent slaves alive.

This 15-metre Jerunai was dropped on top of slaves

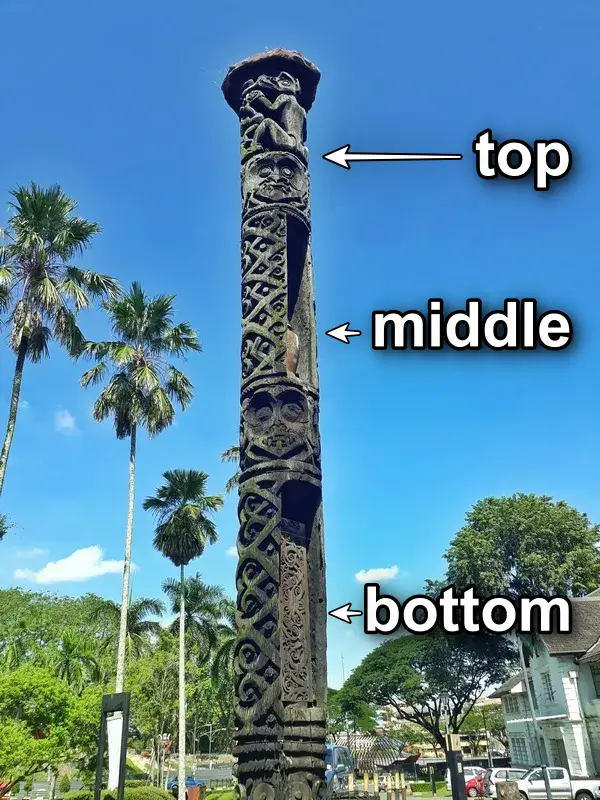

The Jerunai is made out of 3 compartments: Top, middle and bottom. The middle and bottom compartments were used to house the skeleton or remains of deceased aristocrats as well as certain belongings like jewellery and other valuable items. These material items are said to accompany the aristocrat in the afterlife. With that said…

The top compartment is where the slave, who was chosen by the aristocrat when they were still alive, would be bound and left to die a slow and painful death, most likely of thirst and starvation. The slave, usually an orphaned teenage girl, would be chosen for the human sacrifice, so that she can accompany the aristocrat in the afterlife as their servant.

And if you think that’s bad enough, this ritual actually involves the sacrifice of two slaves instead of one. Before the Jerunai is planted in the ground, a hole 4-metres wide and 10-metres deep would be dug to house it. After that hole is dug, another slave would be placed in that hole alive before the Jerunai is dropped on them – killing them and burying them simultaneously.

It is said that before these human sacrifices were done, a traditional song is played to prevent the slaves from becoming vengeful spirits after they have passed. Despite that, many villagers still hear screams and roars in the cemetery after the slaves have passed on, which deter people from disrespecting the burial grounds of the aristocrats. I mean, if your boss dies and instead of just attending the funeral, they campak you into the grave with him, wouldn’t you mengamuk too?

With all that said, when did this form of torture end?

A white man arrived in Sarawak and went WTF?

This ritual was practiced hundreds of years ago. During this time, animism – which is the belief that objects, places and creatures all possess a soul, not waifu worship okay – was the main belief of the Melanau people. However, when other religions began sprouting in Sarawak, most notably Islam in the 15-16th century and Christianity in the 18th century, the ritual slowly began to die. It is believed that the villagers were starting to see that human sacrifices, despite being part of their beliefs, were a grave sin.

But how did it die completely?

Well, when British soldier and adventurer, James Brooke became the Rajah of Sarawak in 1842, he banned the ritual due to its cruelty. Despite this, some Melanau people continued the practice until the last recorded Jerunai in 1880.

Now, the Jerunai has become a historical artefact and there are at least 4 of these burial poles still standing to this day. If you’re wondering where you can find these poles, they’re located in Kampung Tellian Tengah, Mukah. Since the history behind these poles is so dark, you’d think that people would leave these Jerunai alone so all of the spirits can be at peace, right?

Oh, c’mon now…

The Jerunai burial grounds are a popular tourist attraction

It’s not surprising that the Jerunai have attracted tourists over the years. Visiting these artefacts as a sideshow on your vacation is arguably the most interesting way to learn about tragic historical events in an easy and entertaining way, even if these artefacts house unimaginable suffering and pain. According to Lamin Dana Cultural Boutique Lodge’s (which is located in Kampung Tellian Tengah) resident manager, Andrea James,

“The foreigners are never frightened by these stories. Actually, they find them interesting.” – via Dayak Daily

In present day, the Jerunai are protected only by a small 2-foot high fence surrounding the poles. And if you’re thinking, eh tu budak kecik pun boleh masuk… Well, you’re right.

According to the owner of the house next to the Jerunai, many people would disturb or disrespect the poles and they would often get sick because of it. To remedy the illnesses, sawdust made out of wood cuttings from the Jerunai would then be mixed with water and turned into a medicinal drink.

Maybe Sejarah in schools should focus on more than just Parameswara

Sometimes, when we look back on our history, we tend to think, “Gila ke apa buat camtu?” and while that’s valid in more instances than just this one ritual, it’s also important to understand why certain beliefs were upheld in the first place. Be it because of religion or aristocracy, people would normally act in a way they think is right. At the time, giving praise to those who served their community seemed to be the best way to repay their kindness – even if it meant sacrificing innocent lives.

Thankfully, after new religions emerged in Sarawak and the presence of foreign eyes provided a different outlook to the Jerunai, the Melanau people realised that there were better ways to respect the dead without adding to the body count. And while that progress is greatly welcomed, we shouldn’t forget the pain and suffering felt by these slaves hundreds of years ago.

Remembering our history is crucial in respecting the people who were once affected by it, but it is also a way to prevent ourselves from repeating it. The history of the Jerunai could be food for thought the next time we praise rich people for doing the bare minimum.

- 113Shares

- Facebook73

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn9

- Email7

- WhatsApp17