Malaysia may send back some 20,000 refugees to Myanmar, but they aren’t Rohingyans.

- 922Shares

- Facebook860

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn13

- Email13

- WhatsApp26

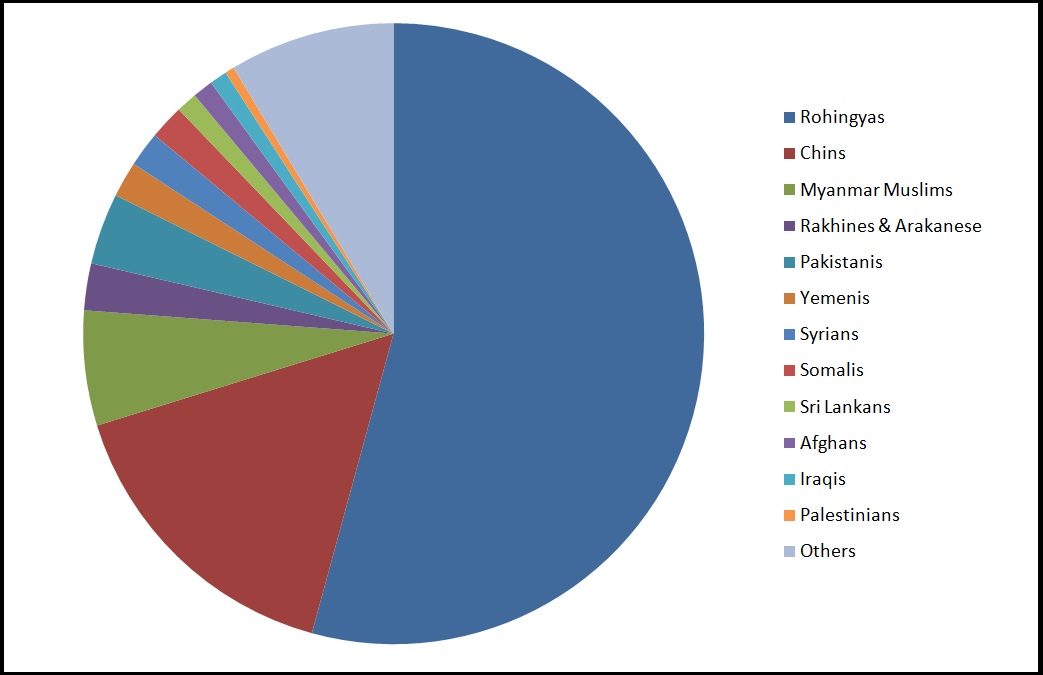

We’re pretty sure that by now, most of our readers know that there are refugees living in Malaysia, and probably the most well-known and numerous among them are the Rohingyans. As of December last year, UN numbers reveal that there is a total of 163,380 registered refugees and asylum-seekers in Malaysia, and Rohingyans make up slightly more than half of that (88,880; or about 54%).

But how many of us know about Chin refugees and asylum seekers? With 26,180 registered with the UNHCR (UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees) and an estimated total number of 40,000 in Malaysia, the Chins are probably the second largest group of refugees and asylum seekers here. However, they now face an uncertain future as the UNHCR might not recognize them as refugees anymore, which means that they will technically be illegal immigrants, and might be sent back. We’ll get to that in a bit, but before we get any further, a bit of technicality because this can get a bit confusing.

- Displaced persons are people who had to leave their own country for reasons like armed conflict, unfair persecution etc etc. They include refugees and asylum seekers.

- Asylum seekers are people who ask for protection from the country they ran to, and

- Refugees are asylum seekers who have been officially recognized as such. Until then, they remain as asylum seekers.

The media often refer to all three categories as just ‘refugees’, so when we’re talking about ‘Chin refugees’ in Malaysia we may mean all three kinds unless explicitly stated otherwise. Also, in light of that, the title may be a bit inaccurate heheh #ihatecilisos. Now that that’s out of the way, if this is the first time you’ve heard of them (like some in the Cilisos office), you might be wondering…

Who are the Chin, and why are they here?

The displaced Chins, Rohingyans, Rakhines, Arakanese and Myanmar Muslims in Malaysia all fled the same place: Myanmar, and they make up the bulk of the refugees here. You may have a rough idea that Rohingyans are being persecuted for being Muslims, but Chins are predominantly Christian. So why are they running? As it turned out, way back in Myanmar’s history, when it was still called Burma, there’s this policy called Burmanization, where Burma tried to come up with an identity that’s Uniquely Burma™.

Now this is an oversimplification of the history, but basically Burma tried to turn everyone Burmese, which is a specific ethnic group on its own. That means that everyone should speak Burmese, act like the Burmese and practice their version of Buddhism. At it’s mildest, the unique cultural identity of other ethnic groups are washed away and replaced with the Burmese culture, and at its worst, some would say it involves ethnic cleansing.

To that end, Christian Chins have been persecuted for participating in Christian activities, and some were forced to convert to Buddhism. Back in 2007, a memo titled “Programme to destroy the Christian religion in Burma” was leaked to the public, and while the regime had denied the authorship of the document, they made no public attempt to deny its contents, either. Burmese soldiers have been reported to harass the Chin public, extorting food and money from villagers, forcing them to do heavy work, and raping their women.

Those who support (or is suspected to support) pro-Chin and pro-democracy associations like the National League of Democracy, the Chin National Front (CNF), or its military arm the Chin National Army (CNA), were caught and tortured, and sometimes killed. Under these conditions, many Chins fled the country, mainly to India and Malaysia, but also to Thailand and Nepal. Since then, a lot of Chins have been resettled to other countries (more than 65,000 between 2005 and 2007). Still, a large number remained in Malaysia, and now they’re making headlines as…

The UNHCR is saying that the Chin people no longer need protection

Sometime in June last year, the UNHCR announced that as of 2020, the Chin people will no longer be considered as refugees, saying that the situation in the Myanmar Chin State is now ‘stable and secure‘. This withdrawing of refugee status is called a cessation, and it is estimated to affect some 30,140 Chin refugees in Malaysia and another 3,000 in India. While it may seem drastic, the reason behind it may have something to do with what’s happening in Myanmar for the past few decades.

While before some had called Myanmar an ‘institution of torture‘, ever since a civilian party led by Aung San Suu Kyi won the 2015 elections, things seem to be improving in Myanmar, especially since a ceasefire agreement had been signed by the military and some ethnic group fighters. Myanmar is now seen as a country in transition, where the former ruling regime peacefully gave up their rule in favor of democracy and equality. However, this new perception of Myanmar translates to a new perception of their refugees as well.

Some are now suspicious of refugees from Myanmar, thinking that they are no longer ‘real’ refugees, and even before the announcement of the UNHCR cessation, there had been reports of reduced funding for refugee programs, with donors redirecting their money to more visible crises. After the cessation announcement, the number of registered Chin refugees and asylum-seekers in Malaysia had dropped a lot, from 31,150 before the announcement to only 26,180 as of December last year. The cessation meant that Chin refugees can either:

- Go along with it and return to Myanmar,

- Renew their refugee card, which will still be valid until the end of 2019, and lose all protection starting 2020, or

- Go through the refugee verification process again to prove that they still need protection, but if they fail, they will lose all protection they currently have.

…so the drop could mean that a number of them did not take the second option, or took the third and failed. Still, the majority of resettled refugees in Malaysia last year were Chins, so that could also be a reason. As Malaysia had not ratified UN’s 1951 Convention relating to refugees and its 1967 Protocol, some might say that a refugee status may not mean much in Malaysia. However, it does open the path to resettlement, and people considered as refugees by the UNHCR will generally not be sent back by the government.

While the choice between going back home or becoming illegal immigrants may be easy for some, despite the seeming peace in Myanmar Chin’s State…

Some would say that going back to the Chin State is not a good option yet

News on how displaced persons are being treated in Malaysia are rarely positive, and as a 2006 fact-finding report had found, it’s the same for Chins who found their way here. Still, there is a fear among the community about being sent back, and within the past year (after the cessation announcement) the Chin in Malaysia have reportedly experienced higher rates of depression, anxiety and suicide ideation. It would seem that the fear is not unfounded, as the conditions in Chin State are not as stable as the UNHCR might suggest.

The Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO), who have been monitoring the situation there, had claimed that there were at least four occasions in 2017 when people had to run to India to escape the conflict between the Arakan army and the Myanmar military, and reports of violence had continued to come in, particularly on the southern border, where according to Edith Mirante, who has worked on Chin issues since the 1980s, is the training grounds for the Arakan army. Their presence is said to draw the Myanmar military (the Tatmadaw) to the area, leading to skirmishes.

“They drew the Tatmadaw (the Myanmar army) in and that sent Chin people fleeing across the border in late 2017. The Tatmadaw presence is quite high throughout the state. Every town has a garrison of troops. It’s certainly a very intimidating presence for the Chin.” – Edith Mirante, to al-Jazeera.

James Bawi Thang Bik, from the Alliance of Chin Refugees, reported that Chins are still arriving in Malaysia at a rate of about 200 a month, and those who returned to Myanmar would often come back quickly to Malaysia, as the situation is not yet stable there. With all these skirmishes and military presence causing tension in the area, some would say that a huge number of Chin refugees returning may make things even worse. Knowing all this, one might wonder…

Will Malaysia really send them back to the Chin state?

Simply put, as of the time of writing there have been no official announcements yet, but judging by news reports, the answer for now is no. According to a response by our National Security Council (NSC) to R.AGE, despite not signing the 1951 Refugees Convention or its 1967 Protocol, Malaysia respects the principle of non-refoulement (not sending refugees back to where they were running away from), and if a refugee has a valid reason of fear as determined by the UNHCR, Malaysia will do its best to extend its protection to the said person, until it’s safe for them to return.

However, in the same statement, it is also stressed that Malaysia has no intention to provide a permanent refuge for any refugees, and that the government would reserve itself from making any statements until the UNHCR officially notifies them about it. Yup, Malaysia has yet to be officially notified of the matter by the UNHCR since the announcement last year. This may be an unusual thing, as according to the secretary-general of the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network Themba Lewis, previous cessation announcements were usually done after a three-way agreement between the UNHCR, the refugees’ original country, and the host country.

As for the UNHCR, they have said that the decision is not set in stone. They are aware of the concerns surrounding the issue, and are constantly reviewing the situation, aware of the fact that ‘things can change, and can change very quickly’.

“…UNHCR is continually monitoring and assessing its individual review policy for the Chin in all countries in which they are present, and remains committed to ensure its approach to the protection of all refugee populations reflects changing conditions and new developments,” – UNHCR statement, Feb 8, as reported by the Star.

They had also recently published a statement saying that Myanmar is welcoming Chin refugees back, but the statement was met with reservation by Chin community leaders in Malaysia. We may update this article in the future if new development comes up, but for now, some had suggested for the government to make things a little better for refugees in Malaysia, such as by allowing them to legally work and giving them access to basic healthcare and education.

- 922Shares

- Facebook860

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn13

- Email13

- WhatsApp26