OMG… there’s an old Malay community in South Africa?! How are they different from us?

- 633Shares

- Facebook509

- Twitter16

- LinkedIn23

- Email22

- WhatsApp63

Growing up, we wouldn’t have thought much about Malay communities living outside Malaysia. Maybe they’re only in parts of Southeast Asia. But did you know that there are Malays in South Africa too? And they’re known as Cape Malays. No no no, not the superhero cape la… Cape as in the huge piece of land sticking out into the sea, like this.

Now, you may wonder why they’re called after a protruding land. Cos they mainly live in Cape Town lor.

But before we begin telling you their story, here’s a little… err.. warning: Be prepared to see a bunch of Dutch names/words which may be unfamiliar to most of you. You can attempt to practise pronouncing them later.

Okay? Now, hold tight.

Hmmm… How did the Malay community end up there?

It turns out that these Cape Malays were descendants of the slaves brought from the East Indies (a.k.a. the Southeast Asian Archipelago). OMG!! Slavery is the reason (psstt, if you want to learn more about slavery, you can read this CILISOS article). Who brought the slaves there and why? What may remind you of a sejarah textbook section about Dutch colonisation, which was in BM, is the word Belanda.

Basically, in the 1600s, the Dutch East India company (a.k.a VOC which stands for “Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie“) needed cheap labour to keep their business empire going, so they enslaved so many people from their colonies including Malaysia and Indonesia. Demand for slaves resulted in a huge global slave trade which forced many Asians and Africans to move across the world.

Even the exiled leaders who opposed Dutch colonisation in their respective countries and Malay servants of Dutch officials returning to the Netherlands were among the slaves brought to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. The Cape was like a pit stop for Dutch ships sailing between the Netherlands and their Eastern colonies.

As the slaves could relate to each other about their tough slave lives, the Malay slaves became close friends with slaves of other origins (from other parts of Africa and Asia). Over time, intermarriages started happening between the Malay and non-Malay slaves, eventually forming a mixed Malay community now known as the Cape Malays. Tadaaaa!

As we said earlier, exiled political leaders did not escape slavery. But they did not stop being leaders either. In fact, they were really important in the salvation of the Muslim slave population and the creation of the Cape Malay community.

These VVVIPs have tombs built in their honour after they died

Surrounding Cape Town is the “holy circle” of these tombs, known as kramats. The kramats are Islamic shrines which mark the graves of the Saints of Islam who played a crucial role in creating what Cape Town is today. They contributed to the Afrikaans language, intro-ed Islam to Southern Africa, set socio-religious boundaries and had suburbs named after their homelands (like Macassar). The Islamic enlightenment in Cape Town was seen as the ticket to the slaves’ fight for FFRREEEEEDOOOMM.

There were over 20 Muslim spiritual leaders including Sheikh Yusuf, Tuan Guru and Sheikh Abdurahman Matebe Shah. But for simplicity, let’s focus on Sheikh Yusuf’s contribution.

Sheikh Yusuf was born as Abadin Tadia Tjoessoep in 1626. While he was studying Arabic and religion in Mecca, his homeland Makassar was occupied by the Dutchmen. Since he couldn’t return there, he went to Banten, where he taught the Islamic doctrine “Khalwatiyyah” and later met Sultan Ageng, who hired him as a Shariah judge and personal consultant. The sultan even matchmade Sheikh Yusuf with his princess.

He soon ganged up with Sultan Ageng to rebel against the Dutch. But after 16 years, the Dutch provoked Sultan Ageng’s son to cari pasal with Sultan Ageng. After losing to the son, BFFs Sultan Ageng and Sheikh Yusuf had to flee with hundreds of other people.

But Sheikh Yusuf was captured and exiled to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Then, the Dutch wanted to send him further away, so they shipped him off to South Africa. In April 1694, he and 49 other Muslim exiles from the East Indies arrived at the Cape aboard the Dutch ship called “de Voetboog”.

To stop his influence from spreading to the rest of the Muslim slave population, Sheikh Yusuf, his family and followers were sent to Zandvliet farm (at least a present day 2-hour-drive from Cape Town and they weren’t driving fast cars back then). Under his leadership, the Zandvliet gang laid the foundations of the Muslim community in South Africa. So, the Dutch occupants’ plans to isolate them didn’t work since the slaves bersatu padu. Zandvliet then became a spot for minorities to gather and rally. Hailed as a transnational hero, his legacy still lives on.

But as amazing as the thought of visiting the kramats may seem, don’t cha wish you could meet the Cape Malay people too? Well, the good news is… You can.

Welcome to Bo-Kaap, where the Cape Malay community lives

If you happen to go jalan-jalan in present-day Cape Town in search of Cape Malays, just head to Bo-Kaap where your search becomes Difficulty Level Zero. The Cape Malays used to live in Zandvliet, District Six and De Waterkant, but when the Group Areas Act showed up during the apartheid regime, they all were forced to move out.

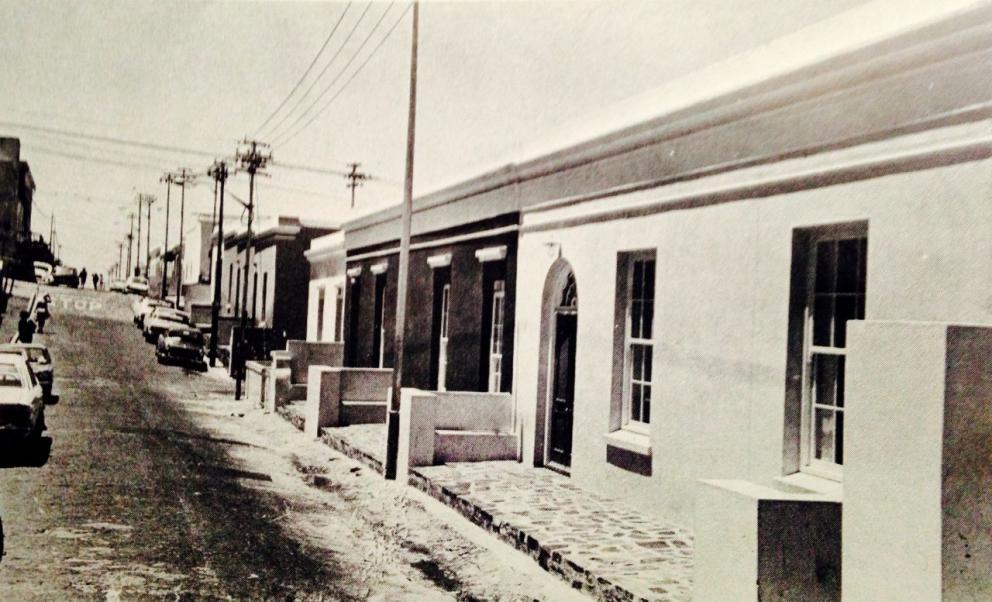

Previously known as the Malay Quarter, Bo-Kaap’s origins started in the 1760s when a Dutch church officer bought the Bo-Kaap land. He then built several small “huurhuisjes” (rental houses) on this land and rented them out to his slaves. After the slaves were freed in 1834, more cheap houses were needed for the freed slaves, so more huurhuisjes-es were built to meet the demand.

Thinking back to the Zandvliet peeps earlier, many slaves think of Islam as the religion of freedom. Because of this, by 1824, arose 2 mosques, 5 suraus and 4 madrasahs in Bo-Kaap. After 1840, more mosques were built, hence attracting many Muslims to move to the new parts of Bo-Kaap.

The colourful rows of homes started appearing after the City Council had to restore the area in the 1960s and 1970s. There are two reasons why they’re so rainbow. One: when the houses were on lease, all the houses had to be WHITE! After this rule was lifted and the slaves could buy the houses, they painted their houses with vivid colours to express their FFRRREEEDOOOMM!!

And two: According to Paul Tichmann of the Bo-Kaap Museum, the colourful houses are related to the celebration of Bo-Kaap’s Muslim heritage.

“Muslim people in the Bo-Kaap would paint their houses in preparation for the celebration of Eid… Neighbours would often agree on what colours to use so as not to have a clash of shades.” – said Tichmann.

Because Bo-Kaap was later declared as a Malay Group Area, it was spared from destruction and commercialisation to maintain its uniqueness. (Click here if you want to know some of the things to do in Cape Town)

If you get the chance to visit Bo-Kaap, prepare to witness…

Here’s how the Cape Malays are like now

If you want a rough idea (though not generalised) of their appearance and way of speaking, here’s a video for you to see.

Just like us food-loving Malaysians, cuisine is very crucial here, so let’s start with that. Cape Malay cuisine is a major part of South African culture and reflects the historical mixing of different cultures which makes it, well, uniquely South African. The Malay slaves added their homeland flavour to the food they cooked in their Dutch masters’ kitchens.

But since the Dutch palate isn’t generally used to our pedas flavour, the food ended up being mildly spicy, fragrant and aromatic instead of super spicy (CILISOS can’t be offended). Later on, groups of people of other races like the English, French, Indians and Germans added their own flavas to the cuisine. And since the Cape Malay community is predominantly Muslim, you can find a lot of halal dishes in Cape Town.

One not nuff. Here’s another one. Yums.

Now, here’s the fun part. All this cultural mixing is also reflected in its entertainment. Since the Cape Malay music is as colourful (and complex) as Bo-Kaap, we had a pretty hard time summing it up, so let us show you a video of a Cape Malay choir. Enjoy!

Every 2nd of January, the Cape Malays would hold a Tweede Nuwe Jaar (Second New Year) street party also known as Kaapse Klopse where they put on their colourful outfits and celebrate with music and dance. The significance of this festival arose from its slavery past when the slaves had one day off from work every January 2nd when their colonisers were sleeping off their New Year party hangovers. So they take this chance to freely have fun lor.

But the Malay culture seems to be… fading

Although Malay was commonly spoken by the Asian slaves, its use in Cape Town may be diminishing. Most of them now speak Afrikaans, which is a rojak of African, Asian and European languages.

You may wonder at this point why Malay culture seems to be disappearing in South Africa. It’s not very clear why but maybe the reason is Africanisation: a process which upholds the African cultures and fades out the non-African cultures including those of European and Asian origins which are related to its colonial past.

On top of that, Cape Malay rights are getting pushed aside in light of the gentrification taking place in Bo-Kaap despite Bo-Kaap being a Malay Group Area, resulting in some of them losing their homes. Just like how their ancestors fought for freedom, the Cape Malays’ protests against the developers’ invasion show the awakening of the Cape Malays in defending their rights and their home Bo-Kaap from losing its historical significance and identity.

- 633Shares

- Facebook509

- Twitter16

- LinkedIn23

- Email22

- WhatsApp63