Malaysia is on the road to reduce potholes… by adding rubber to to its roads.

- 516Shares

- Facebook496

- LinkedIn3

- Email4

- WhatsApp13

If you have a driver’s license in Malaysia, chances are you’ve run into a pothole (or at least avoided one) before. Those little buggers seem to pop out of nowhere, and if you drive by the same pothole long enough, you might notice that it gets bigger over time until the authorities finally decide to patch it up.

Potholes are no fun for car drivers, but for motorcyclists, they can be downright deadly. However, they may soon be about as rare as a business complex without a mamak restaurant. Over the past few years, the Public Works Department (JKR) and the Malaysian Rubber Board (MRB) have been tinkering with the idea of using rubber in roads, and as far as research papers and news stories can tell us, rubberized roads are promising in more ways than one.

Today, we’ll be looking at these roads, and you might be wondering…

Will it make the roads bouncy and stuff?

No. No it won’t. Probably. Anyways…

How can rubber possibly stop potholes from rearing their potholey faces?

To understand that, first we have to look at how potholes happen. There are several things that cause potholes (utility companies digging up roads to lay down cables and pipes and not patching it up properly is one), but the kind of pothole we’re looking at in this article is the ‘natural‘ one.

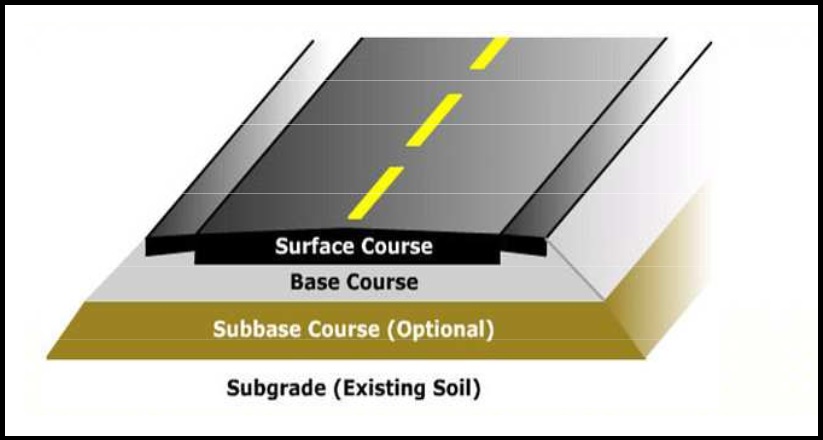

The asphalt roads we have today (known colloquially as tarred roads or jalan tar in Malay) are basically made of three layers: the surface, the base, and the subgrade, which is essentially the ground the road is on. Here, a visual aid:

Of interest is the surface layer made of asphalt, which is something like the Graham cracker crust of a cheesecake. But instead of cookie crumbs, we use small rocks of different sizes (called aggregate), and instead of melted butter, we use something called bitumen, a thick, black, oily liquid that’s left over after you take all the good stuff out of petroleum. Aggregate and bitumen are mixed together to form asphalt at a ratio of around 95:5, poured onto the road base, and compacted to form the road surface we know and love.

Besides binding the aggregate together and making our flip-flops stick to freshly layered road, bitumen also keeps water from weakening the road surface, being waterproof and all. However, bitumen is also thermoplastic, meaning that it softens with heat and turns hard and brittle when it’s cold. And those of us who ran barefoot over asphalt on a hot day knows how hot they can get. With the cycle of expansion and contraction as temperatures change, and cars and trucks zooming across the surface some more, cracks will eventually form.

Rainwater can now seep in through these cracks, and over time they can carve out little pockets under and within the asphalt. These will eventually turn into potholes once a heavy enough vehicle runs over them. Subsequent runs by other vehicles will make the holes bigger.

Gee, if only there’s a way to modify the bitumen to make it less prone to cracks in the first place…

By adding a tiny amount of rubber, the bitumen gains elasticity

If a humble reader such as your fine self can think of modifying the bitumen, you can bet that others have, too. People have been adding weird stuff to bitumen for over a century already, and when the weird stuff is polymers (molecules with really long repeating chains), the resulting product is called polymer modified bitumen (PMB). For example, the USA have been adding rubber crumbs from ground-up used tires to their bitumen, and India have used plastic trash.

Adding polymers to bitumen have different results depending on which polymer you use, but generally the idea is to make the resulting asphalt stronger, stickier, and tougher. Malaysia have experimented with both rubber crumbs and natural rubber in roads since the 1950s, but these incidents are vague, either because they weren’t recorded or people just built stuff and didn’t follow up after.

Then sometime around 2015 the Malaysian Rubber Board (MRB) and the Public Works Department (JKR) got together and studied the effectiveness of adding cuplump rubber to bitumen for use in roads. Cuplump may not sound like a real word, but it is the very real lump of solidified raw rubber found at the bottom of rubber tapping cups. Since they’re practically the product of tapping trees and forgetting about them for a night or so, cuplumps are a lot cheaper and more convenient than, say, grinding up tires or rushing off fresh latex to a bitumen mixing station.

Cuplump is also said to be better than powdered rubber for roads, as the latter tends to act as just a filler to plug up spaces between the aggregate, leading to a more ‘solid’ road surface. Cuplump, being natural, unprocessed rubber, is able to change the property of the bitumen it’s mixed in, making it a better adhesive.

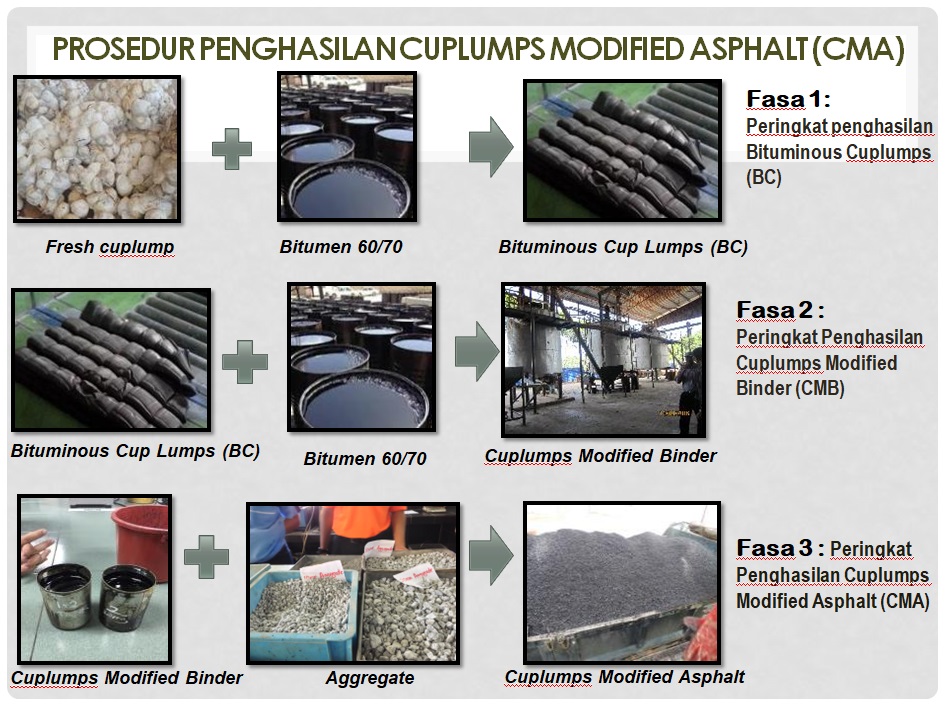

While the MRB had been a bit hush-hush about the actual science behind it in the beginning, basically, cuplumps are added to bitumen to make bituminous cuplumps, and these are added again to more bitumen to make cuplump modified binder. This, when mixed with aggregate, forms cuplump modified asphalt (CMA).

Malaysia is said to be the first in the world to use this specific technology. Initially, test roads were built in Negeri Sembilan, Kedah, and Pahang around 2017, and initial findings showed that besides the usual benefits of PMB mentioned above, roads built with CMA are also quieter (by between 3-5 decibels) and easier to drive on (in that there’s better grip). They are also more elastic, in that the surface still gets squished, but they can gradually snap back in place. Not enough to bounce on, though.

Anyways, perhaps due to the positive findings, the government decided to give it a go and started applying CMA technology to other roads as well. A 40 km stretch of the Yong Peng-Segamat road was said to be the first road in the country to formally use CMA in 2018, but several other roads were CMA-fied even before that, albeit at a smaller scale. In September, Kedah got its first stretch of CMA road (150 meters between Alor Setar and Kuala Kedah), and last month plans were announced to use CMA in 2 km of a road in Kadamaian, Sabah. If that plan goes through, it will the first rubberized road in Sabah.

With us talking it up so much (totally based on reports and papers), it should be noted that…

There’s more behind the push for CMA than just better roads…

As of February 2019, a total of 46 kilometers of rubberized roads have been completed using the CMA technology. With RM100 million allocated in Budget 2019 to build more CMA roads in ports and industrial areas, we’ll probably be seeing more of them soon. The government seems pretty keen on rubberizing our roads, and seemingly for good reason.

Granted, CMA roads are a lot more expensive to build than regular asphalt roads. Conventional asphalt roads cost around RM29.90 per square meter to build, while CMA roads cost almost double that, at RM53.60 per square foot. However, it might be cheaper in the long run.

Roads built using rubber polymers are said to last longer, and it is said that a 50-kilometre stretch of road near KLIA built using rubber crumbs have yet to be re-asphalted since its construction in 1998. Normal roads usually need to be re-asphalted (re-surfaced?) after 4 or 5 years to fix the potholes, cracks, slumps and dents that develop, but using polymers in the bitumen is said to extend the time between resurfacing to 8-10 years.

But there’s another goal for promoting CMA. It’s not really a secret, but by using raw rubber as a building material in roads, the government is hoping to increase domestic use of our rubber. The global rubber market has not been looking good lately, with oversupply causing rubber prices to stay down. To deal with the slump, some have pointed out that rubber producing countries, like Thailand for one, have been lobbying for the use of rubberized asphalt as well as using it themselves to boost demand internally. Malaysia seems to be doing the same.

For every kilometer of road (or 6,000 square meters) built using CMA technology, an estimated 4.2 tons of cuplump rubber is needed. With that kind of usage volume, converting just 5-10% of federal roads on the Peninsular alone would significantly boost domestic demand for rubber, hopefully affecting the price.

And the ones to benefit the most from this initiative is some 440,000 rubber smallholders in the country, as it is said that 95% of cuplump production comes from them. As put by Primary Industries Minister Teresa Kok,

“These rubberised roads could help raise the incomes of some smallholders involved in the planned rubber supply chain model, and this project is expected to significantly increase the use of local rubber in future if continuously implemented,” – Teresa Kok, as reported by Malay Mail.

Wait. Isn’t that another plus? We can’t really find anything bad to say about rubber roads except for the price. Probably because no one cares about rubber roads the technology is still pretty new. We’ll probably update the article once a scandal comes up. Until then, hurray for rubber roads!

[This article is totally not sponsored. But if someone wants to sponsor… we won’t protest wan.]

- 516Shares

- Facebook496

- LinkedIn3

- Email4

- WhatsApp13