The Bugis community recognizes FIVE genders. How does that even work?

- 8.1KShares

- Facebook7.8K

- Twitter29

- LinkedIn45

- Email62

- WhatsApp159

Most people don’t think too much about gender. When you’re born, the doctor takes a look at the space between your legs and say, “Congrats! It’s a boy/girl!”. Most parts of the world recognize only two genders, males and females.However, for some people, gender isn’t as simple as that.

There are people born with abnormalities such as an androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), where a human’s body with XY chromosomes (essentially a male) cannot respond to male hormones, resulting in a male with a female’s appearance. Then there are Intersex people (previously called hermaphrodites) are born with either the genitals of both sexes, or have both male and female chromosomes at once.

Some countries in South Asia legally recognize a third gender, the hijra which is sort of transgender. Native American Indians also recognize a separate third gender, berdache (now called two-spirit). Berdaches are believed to be the “dusk” that lies between the male morning and female evening.

And then there are the Bugis of South Sulawesi, who we recently read recognize FIVE separate genders!!

What?! Five genders? What are the other three?

The Bugis is an ethnic group that originated from South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Due to migration, Bugis communities can be found everywhere, most notably in Sumatra, northern Australia and Malaysia. In fact, some famous Malaysians are of Bugis descent – actress Lisa Surihani, singer Yuna, the first Sultan of Selangor, Sultan Salahuddin Shah, PPBM’s Muhyiddin Yassin, and of course, our own ‘Bugis warrior’ PM Najib Razak (although he doesn’t seem to agree with this part of his ancestry).

The original Bugis in South Sulawesi recognizes the existence of five separate genders. In fact, each of the genders are expected to live in harmony with each other.

“There are five genders, and we don’t need to separate people by their gender because everything must live in harmony. If one of the genders are separated, then the world will become unbalanced.” – Pawang Matoa, for National Geographic.

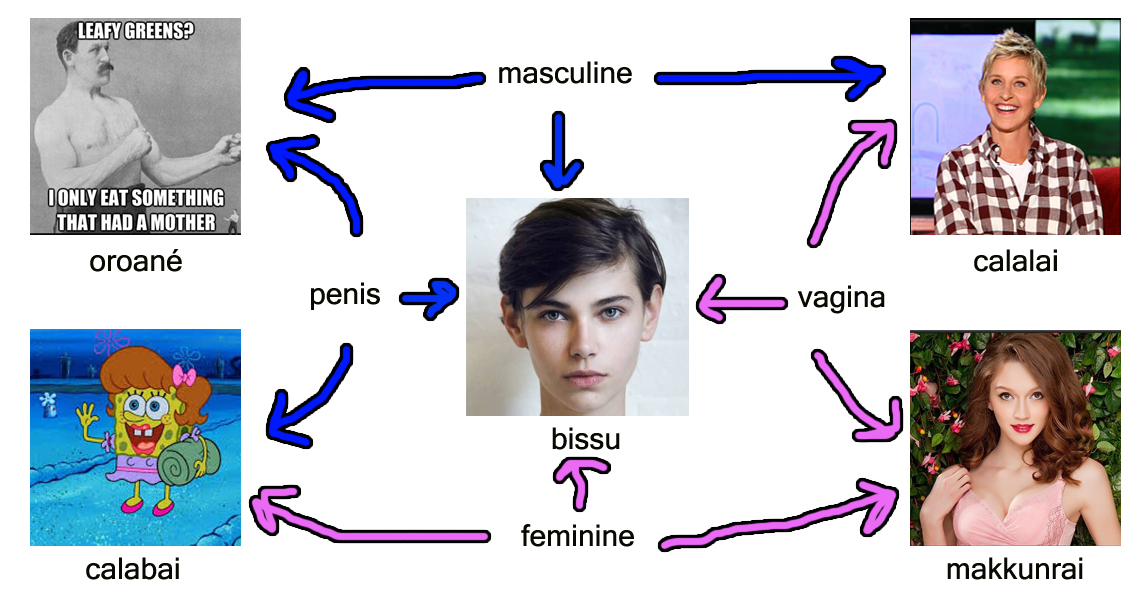

They’re, simply:

- makkunrai, womanly women

- oroané, manly men

- calalai, manly women

- calabai, womanly men

- bissu, a sort of combination

In respect of genitalia, the calalais have female parts and the calabais have male parts. You could say that counterpart to calalais could be tomboys or ‘pengkids’. They do traditional men’s work like blacksmithing and dress like men. They may smoke, go out alone at night, or basically do anything that a man can traditionally do without anyone batting an eye. It is normal for calalai to have a family with a wife and adopted children.

The calabai, on the other hand, are more feminine. A close Malaysian counterpart might be the pondan, but not exactly. The calabai do not consider themselves as a member of the opposite sex, nor have any wish to be one. While calalai are women acting like men, the calabai carved out a niche role for themselves in the community, usually being an indo’ boting (wedding mothers, or mak andams) or something close to that.

To make it a bit easier to understand, here’s an approximate artist’s interpretation of the genders:

Unlike the norm in Malaysia where the calalai and calabai might be subjects of harassment, as mentioned by Pawang Matoa earlier, they are seen as essential to the gender system. Bugis society in olden times accepted them, and Jamal Mohamad, the programs manager for Singapore’s Malay Heritage Center recounted seeing calalais and calabais publicly dancing in Singaporean Bugis weddings (joget pondan) back in the 1980s.

“These were groups of men dressed up as women who were dancing. That scene has slowly disappeared but that was what we were used to – seeing effeminate men and masculine women who were not queer.” – Jamal Mohamad, for Channel News Asia.

So there you have it. Eh wait, what about the bissus?

Bissus are part man, part woman, part human…and part deity. OMG wuut?

Bissus are a bit different because they are seen as being both male and female at the SAME TIME, whereas calabai and calalai start out as either male or female, then adopt the opposite gender’s role. Bissus are either born with both genitalia at once, or if they only have one type of genitalia, their souls are seen as the opposite sex. In this sense, technically calabais and calalais can be bissus as well, if they wish to be. Confused yet?

Due to their duality, bissus are also seen as the go-between for humans and deities. A Bugis creation myth recounted that bissus were among the first beings on earth.

“You ask how this world came to be? Well let me tell you. Up there in the heavens, the gods decided they would bring life to this lonely planet. They therefore sent down one of their most aspiring deities, Batara Guru. But Batara Guru was not good at organizing things. To do all of this, two bissu were needed. So the gods sent down two bissu who flanked Batara Guru as he descended. And when they arrived, the bissu set about making everything blossom; they created language, culture, customs, and all of the things that a world needs if it is going to blossom. That’s how the world began you see.” – Haj Bacco, for the International Institute for Asian Studies

Another tale claimed that bissus have supernatural qualities due to them being both male and female and mortal and deity.

“Long ago, a man named Sarawigading wanted to marry a woman named WeCudai, but WeCudai lived on an island in the middle of a huge lake. The only way to get there is by boat, and Sarawigading didn’t have one. There was a big tree by the lakeside, so he decided to cut it down and try to make a boat out of it. But the tree was too big, and tried as he might he couldn’t cut it down. Sarawigading burst into frustrated tears and cried long into the night, as the situation seemed terribly hopeless. However, a bissu in the heavens heard him cry and descended to help him. “Please don’t worry, I will cut down the tree and help you make a boat,” said the bissu, and s/he managed to fell the huge tree as s/he had the strength of both man and woman, and mortal and deity.” – Old Bugis narrative from IIAS, edited for clarity

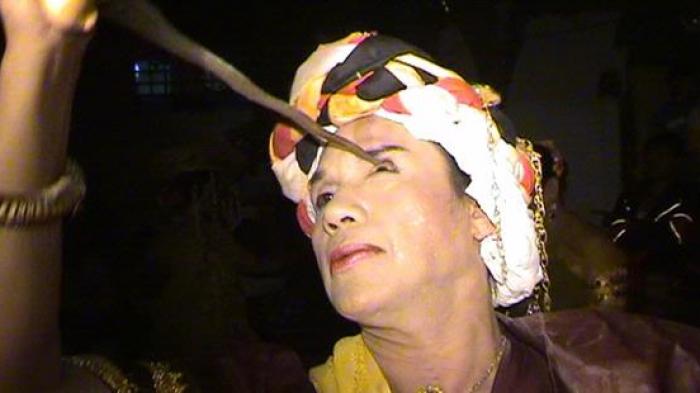

In some ways, bissus are seen as shamans, as they are believed to be the only humans able to be possessed by spirits. To do this, a bissu must have good connections with the spirit world. They have to combine male and female attributes through their clothing – a bissu may carry a man’s knife (badi’) but wear flowers in his/her hair. Not just anybody can be a bissu.

If a child showed an affinity to the spirit world by the time he/she is 12, he/she will be groomed to become a bissu. Traditionally, bissus were required to memorize sacred Bugis texts as well as go through life-threatening inauguration rituals. One of them requires the bissu-to-be to lie on a bamboo raft in the middle of a lake for 3 days and 3 nights without eating, drinking or moving. If he/she survives this and wakes from his/her trance fluent in the sacred bissu language, he/she will then be accepted as a bissu.

A bissu then becomes an important part of society, with some becoming VIPs in royal courts and given their own land and rice fields. Besides having to keep royal regalia and give spiritual advice to the king, a bissu’s main role is to bestow blessings on almost every aspect of the Bugis community’s life… from rice planting, marriages, building a house, or blessing people going to Mecca on a pilgrimage.

Eh what? Going to Mecca on pilgrimage? You mean they are Muslims? Technically, they are, as…

There was a time when a Muslim community tolerated more than two genders

In Malaysia, it’s been ackknowledged by our PM that being transgender and cross-dressing do not go well with Islam. The government had repeatedly tried to address the issue, either through videos to help them repent or through forced rehabilitation camps. Cross-dressing or transgender events would warrant a raid by the religious authorities. So how can a bissu, someone who is both genders at once, bless someone going for hajj in Mecca?

As is the case with some cultures introduced to a new religion, the Bugis managed to take elements from both religions and made it work together. According to Sureq Galigo, the Bugis creation myth, there was a supreme deity called Papunna, and from Papunna came a male and a female that got together and gave birth to a varying number of deity couples. These couples were assigned to look over various levels of the world, with the male of the couple residing over the summit of Heaven being Datu Patoto, aka the ‘prince who fixes destinies‘.

Many Bugis came to believe that Patoto is just another name for Allah, the Muslim God, and while bissus may call upon various other deities to possess them, the deity-calling always begins by seeking Allah’s blessing and advice first. On the other hand, some older Bugis practices like walking on fire have been abolished by the bissus as they believed it to be contrary to the teachings of Islam. While these practices may seem contradictory to some, to the Bugis they are not.

A cultural researcher recounted that the Bugis worldview in South Sulawesi was that Allah is the one and only God, but Allah has helpers, and they are the dewata (other deities). However, these beliefs and practices didn’t sit well with some:

“When Indonesia gained independence, the bissu lost theirs.” – Halilintar Lathief, Hasanudin University’s anthropologist, as quoted by Al-Jazeera

While some people may marvel at the five-gender system and see this as an example of a tolerant society, the truth is far more gritty. As Halilintar said, when the Dutch let go of Indonesia in 1949, the bissus, calabais and calalais were persecuted and attacked, and sometimes killed in horrifying ways. Some transgendere individuals were forced to shave their heads to ‘display their immorality‘.

Sometime in the 1950s, an Islamic movement called the Muhammadiyah banned bissus, and in the town of Bone an mob reportedly decapitated a bissu leader and paraded his/her head around town, swinging it by his/her long hair. Along with another large Islamic movement called the Nahdatul Ulama, the Muhammadiyah blamed the perversions on the influence of infidel rule. Many went into hiding, either living in caves, in the jungle, or dressing up convincingly as either man or woman.

“Many came under direct persecution from the supporters of Darul Islam and Muhammadiyah owing to their evocation of local spirits and magic, as well as a mildly sensuous or even openly erotic nature – putting them at odds with the teachings of orthodox Islam. Many of the local people I spoke with remembered these Muslim forces killing bissu, smashing drums and other instruments, and destroying local female dance costumes, such as the short-sleeved baju bodo (deemed too risque, as it exposed the female arm).” – R. Anderson Sutton, writer of Calling Back the Spirit: Music, Dance and Cultural Politics in Lowland South Sulawesi.

All of these contributed to the less sensational part of the story of the community with five genders, which is…

Once a community’s culture is dead, it can be hard to resurrect

According to a 2015 report, the town of Gowa, Indonesia, had no more bissus. In the town called Bone, there were only two bissus left. A nearby town called Sigeri only had four, despite having 40 official bissus in the past.

“The rumor at the time was that if someone saw a lady-boy or transgender, for seven days their good deeds would not be accepted by God. They were banished. All of that trauma lasted several generations. It is amazing there are actually any bissu these days.” – Halilintar on Al-Jazeera

However, another reason may be that transgender people today have more options. Many young calabais now earn their living by working in salons, providing beauty services or organizing weddings, which is a lot more lucrative than being a bissu with no monthly income.

“Right now the calabai see the responsibility of bissu as really hard. If you are a bissu, there is a great responsibility. When there is an event, they must attend. But the calabai are busy.” – Miska, a transgender English teacher, for Al-Jazeera

There had been efforts to preserve the bissu culture. In the late 1990s, Halilintar’s organization, Latar Nusa started a program to bring the bissu in Segeri out of hiding, arranging meetings between them and the local community and so on. It was somewhat successful, with the first bissu in decades inaugurated in 2002. Bissu rituals have since become a thing again in Sigeri, but the future is uncertain. Halilintar’s program ended in 2003, and the last head bissu of Sigeri died in 2011.

Cultural heritage, while often overlooked in favor of progress or other factors, is an important aspect of who we are. It can be said that a people without a culture has no identity, and can be likened to a person without neither a face nor a name to call their own. The five-gender system recognized by the Bugis is an example of an intangible cultural heritage, which are cultural things that you can’t really touch or hold, like oral tradition (passing down unwritten knowledge through the generations) or ethnic dances and songs.

While there are many threats to intangible cultural heritage, perhaps the most common one is globalization, specifically cultural globalization, where the ideas, meanings and values of different communities can reach and influence other communities with a different set of ideas, meanings and values. Sometimes, this results in hybridization, like when the Bugis people combined their myths and beliefs with Islam and made it work.

However, it can also result in homogenization, which is when local cultures are transformed or absorbed completely by a dominant outside culture. This means that a community’s original culture is completely replaced by a new, foreign culture. While some may argue that cultural homogenization have its benefits, it ultimately results in less culture diversity, and a loss of national identity.

Malaysia isn’t immune to the effects of cultural homogenization. In 1998, a traditional dance called the Mak Yong as well as a slew of other cultural performances such as the Wayang Kulit, Menora and Main Puteri were officially banned by the Kelantan state government following the passing of the Entertainment and Places of Entertainment Control Enactment. The ban was believed to be due to these performances having pre-Islamic elements, and also for not being very Islamic.

“The aurat thing was part of it. Cross-dressing was also partly the issue. But they came down heavily on women, because women were not supposed to be seen on stage,” – Eddin Khoo, cultural activist, for the Malay Mail Online.

Despite it being banned, some people are trying to keep the tradition alive. The Unesco, for one, had urged the state government to lift the ban on various cultural treasures in Kelantan. Groups like Seni Pusaka supports the performers who’ve kept their heritage alive through exposure and preservation efforts. And of course, the practitioners of the arts themselves are working hard to ensure their knowledge will not disappear by passing it down to the next generation.

Even though Halilintar tried hard to preserve the cultural identity of the Bugis, and the Seni Pusaka tried hard to support the cultural practitioners, ultimately whether a cultural thing lives on or dies out depends on the people who practice them.

“That’s why all the institutional forces want to clamp down even harder. Because communities have decided to live and thrive on their own despite all this. I think this is a very positive thing. The politicians will always have their politics. The ideologues will always have their ideology. But culture has a far greater hold on the lives and spirit of the communities,” – Eddin Khoo, for the Malay Mail Online.

- 8.1KShares

- Facebook7.8K

- Twitter29

- LinkedIn45

- Email62

- WhatsApp159