The first to enjoy electricity in Malaya wasn’t the British. It was two Malayans in 1894.

- 12.4KShares

- Facebook11.9K

- Twitter30

- LinkedIn37

- Email63

- WhatsApp378

Here’s a quick pop quiz for you guys. Let’s say that you’ve managed to get your hands on Doraemon’s time machine, but as you were returning from photographing dinosaurs in prehistoric Kelantan, the machine’s low battery alert came on. Apparently, the machine uses electricity.

Because of the low battery, you can only pop out of the time tunnel one more time, and only in the space within Malaya. So the question here is… what’s the earliest time and place you can RnR at to recharge your time machine?

If you answered sometime in the mid-1800s, well… we hope you like tin mining and prostitutes and opium, because you’re going to be stuck there for a while. Electricity didn’t come to Malaya until the very end of the 19th century, and even then, very few select places have it. The earliest instance of electricity in Malaya was back in 1894, where..

Two tin tycoons were the first to bring electricity to Malaya

As far as we can tell, a tin mine in Rawang was the first place that used electricity in Malaysia. In Sabah, it was said that electricity was used in the state as early as 1910, and while we can’t find the earliest record of electricity in Sarawak, it was said that their government started looking into it starting from 1921. Malaya‘s experience with electricity was documented in more detail, and the earliest instance of it was credited to two people: K. Thamboosamy Pillay and Loke Yew.

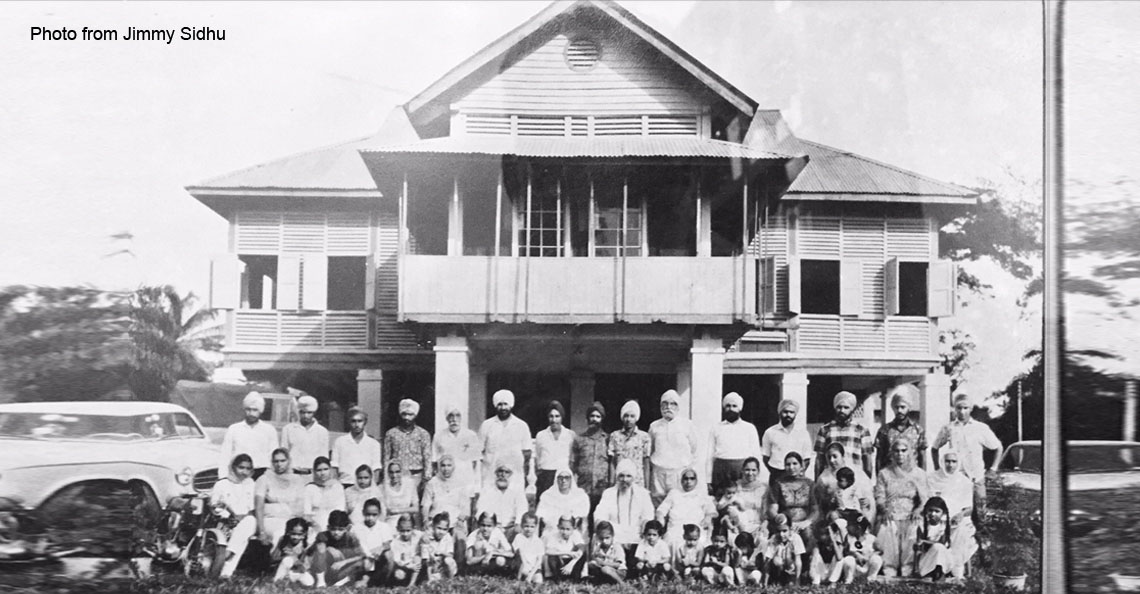

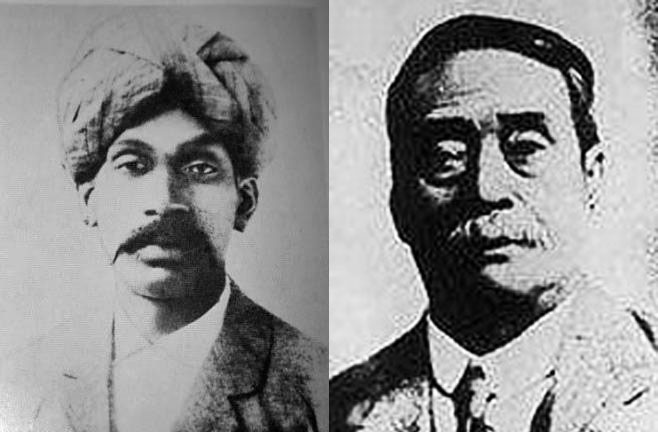

If you’re in KL a lot, you might have noticed that there are roads named after them, which wouldn’t be surprising considering what they’ve done in the past. Besides being the leaders of their respective communities, Thamboosamy was credited for establishing Batu Caves, and both him and Loke Yew were remembered as very charitable businessmen. They were also among the founders of KL’s Victoria Institution, which is why two of their sport houses are named Thamboosamy and Loke Yew.

Anyways, sometime in the 1880s, Thamboosamy got into a partnership with Loke Yew over a tin mining business in Rawang. Their company was known as the New Tin Mining Company, and in 1894 they brought in and installed an electric generator to power electric pumps in their mines. This was considered to be the first time anyone had ever used electricity in Malaya, and within the same year the town of Rawang got electric powered streetlights.

Considering that people in the US were only beginning to find practical uses for electricity just about a decade before that, you could say that Thamboosamy and Loke Yew were quick to the electricity party. The use of electricity spread in Malaya after that, but it wasn’t until a few decades later that people started getting electricity in their homes. In fact, it was claimed that the earliest house in Malaya to get electricity did so in 1920.

However, that doesn’t mean that people were slow to adopt electric power. They just focused on a certain industry…

Mining was responsible for a lot of Malaya’s early electrical development

When it comes to the story of electricity in Malaya, the most detailed account we could find was from this 1966 University Malaya paper written by Robert F. Kinloch, so unless otherwise linked, this is the primary reference. Anyways, up until 1904, with the exception of street lamps, most of the electricity in Malaya were used by mining companies for their businesses. In fact, the first power plant in Malaya was built by one: the Sempam Hydroelectric Power Station in Raub, Pahang, was built in 1900 by an Australian gold mining company.

It wasn’t until 1904 that power plants were built to supply towns with electricity, and they were either hydroelectric plants or thermal, which burned fuels like coal from Batu Arang or local wood and oils. The earliest towns to be supplied by electricity would be George Town, which built a thermal plant in 1904, and KL with a hydroelectric plant the next year. Other towns on the West Coast of Malaya soon built their own power plants, mostly thermal, but they were mostly scattered, and their capacities were all quite small in the beginning.

Up until 1926, the biggest power plant in Malaya was a thermal plant in Prai, Penang, with a capacity of 9.5 MW. By then, tin mining had really kicked off in Perak. Tin miners started using electric gravel pumps and dredges more, and the increased demand prompted the British government to collaborate with tin mining companies to establish the Perak River Hydro-Electric Power Company (PRHEP). This company built the then 27 MW Chenderoh dam, which was considered the biggest civil engineering project in Southeast Asia when it was constructed in 1929.

Thanks to the dam and other similar projects in Malaya that year, the total electrical output by both private and public suppliers reached 230 GWh (or 230,000 MWh). Of those, more than 90% were consumed by tin mines. By 1937, of all the bigger power plants in Malaya, 85% were owned by the PRHEP and mining companies. In fact, up until the war, tin mining used up at least 80% of all electricity produced in Malaya.

Even the Electric Department in the Federated Malay States, whose responsibility was to produce electricity for public use, sold 85% of their electricity to tin mines, particularly around KL. Such was the demand of the tin industry in the early days of electricity in Malaya. This changed after the World War II and the Japanese invasion…

Despite the instability, the government managed to double electric output in the years that followed

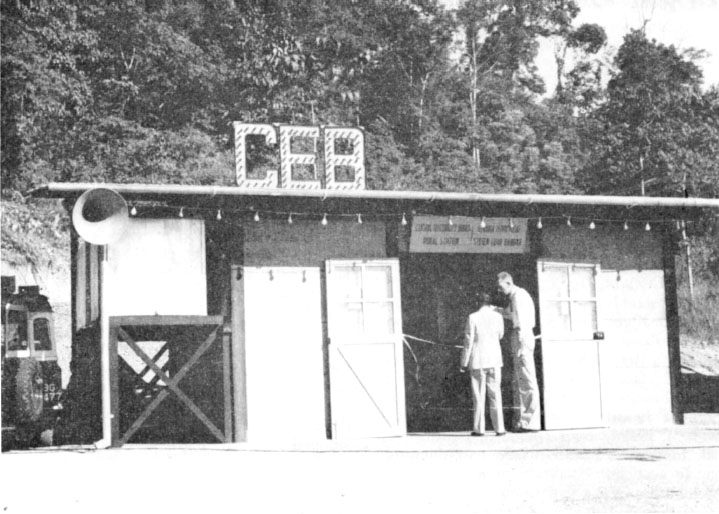

After the war ended, the British returned and did some major revamps. Besides combining the states in Malaya into the Federation of Malaya in 1948, they also combined the government’s electric utilities together under a body called the Central Electricity Board (CEB). This body replaced the Electric Department, and it was tasked with expanding power production to keep up with the rising demand. While CEB didn’t control the production in Malaya absolutely – George Town’s electricity remained independent then, and PRHEP was still a thing – its share in producing electricity grew bigger over the years.

Because of the instability at the time (think Communist guerillas) and a lack of government knowledge of the land, most expansion projects focused on new thermal stations as opposed to hydroelectric dams. This can be seen through the construction of diesel power stations to supply smaller towns and villages outside Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan and Malacca, plus bigger projects like oil-fired Connaught Bridge power station in Klang, as well as steam turbine stations at Malacca and Johor Bahru to keep up with the industry in these areas.

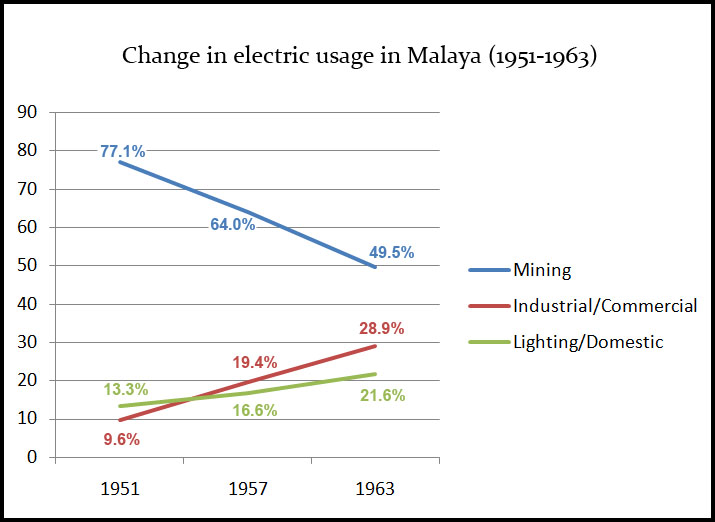

Within just one decade (from 1950 to 1963), the total electricity generated in Malaya more than doubled (from a total of 704.2 GWh in 1951 to 1,621.6 GWh in 1963). And as you’ve probably noticed, the new developments were no longer heavily focused on places where tin mining took place. By 1963, tin mining began to lose its profitability, and its use of electricity dropped to below half of the Peninsula’s total production. On the other hand, electricity usage for industrial and domestic purposes increased during that time.

This was also around the time that Malaya reached independence, and under the First Malayan Plan, the CEB carried out its first rural electrification scheme. This scheme seemed to be centered on using diesel generators to provide lighting on the perimeter of New Villages, which were places where rural people were isolated and guarded by the British in ‘villages’ to lessen their contact with the communists. Part of their plan was winning these people over by providing them with piped water and electricity, so this may have contributed to the increase in domestic usage in those years.

Nevertheless, with more power stations to generate electricity, as well as more places to direct that electricity to, the next step would be to connect everything into one system. So by the time Malaya became Malaysia…

The National Electricity Board came into being, and it later became Tenaga Nasional Berhad

By 1963, there are four main public utility companies: CEB, PRHEP, George Town’s City Council, and another company called Huttenbachs. Sometime in 1965, the CEB was renamed as the National Electricity Board of the States of Malaya (NEB), or Lembaga Letrik Negara (LLN) in Malay. To bring everything together under one company, NEB spent the next two decades acquiring the installations of the other three major players that are scattered all over the Peninsula.

To that end, the NEB took over Huttenbachs’ installations in 1964, Penang’s Municipal Council’s in 1976, and PRHEP’s in 1982. With these assets under the NEB’s possession, it was possible to link everything – the power stations and the people and businesses that use electricity – under something called the National Grid. Think of it as one huge extension wire with multiple heads and sockets sprawling all over the Malaya.

While the plan for it had been around since the Electric Department days, a grid didn’t show up until the 1960s. At first, the Bangsar Power Station was connected to the Connaught Power Station in Klang, with the line extended to Malacca. This was the initial grid that served the central region. This was later linked to the newly-completed hydroelectric Sultan Yussuf Power Station in Cameron Highlands, and by 1965, plans were made to connect other power stations in Terengganu, Perak, Selangor, Pahang, Penang, Negeri Sembilan, Kelantan, Johor, and Malacca.

Kota Bharu in Kelantan was the final point in the grid, and once it was connected in the 1980s, the loop was complete. Sabah and Sarawak has their own separate grids, owing to their separate bodies (SESCO in Sarawak and SESB in Sabah), but that’s another story for another day. Anyways, in 1990, NEB was replaced by a government-owned private company called Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB). And that’s pretty much the story of how we have power lines connecting almost all of Malaya, from a couple of enterprising Malayans who brought in generators for mining.

- 12.4KShares

- Facebook11.9K

- Twitter30

- LinkedIn37

- Email63

- WhatsApp378