The Malaysians who were ‘thrown like rubbish’ to make way for Putrajaya in the 90s

- 3.6KShares

- Facebook3.4K

- Twitter27

- LinkedIn17

- Email18

- WhatsApp136

Not too long ago, the Federal Territories celebrated, uhh, the Federal Territory Day, so in conjunction with that, we wrote an article about a few things about Putrajaya that most of us wouldn’t have known about (which you can read here).

While researching that article, we found a few interesting references to the people who lived in Putrajaya before it was known as Putrajaya. Today, we’re gonna look past the architectural masterpieces, grandeur and eco-friendliness of Putrajaya (can read this article for that), and put the spotlight on a community of plantation workers that might have been forgotten, way back when Putrajaya was known simply as Prang Besar.

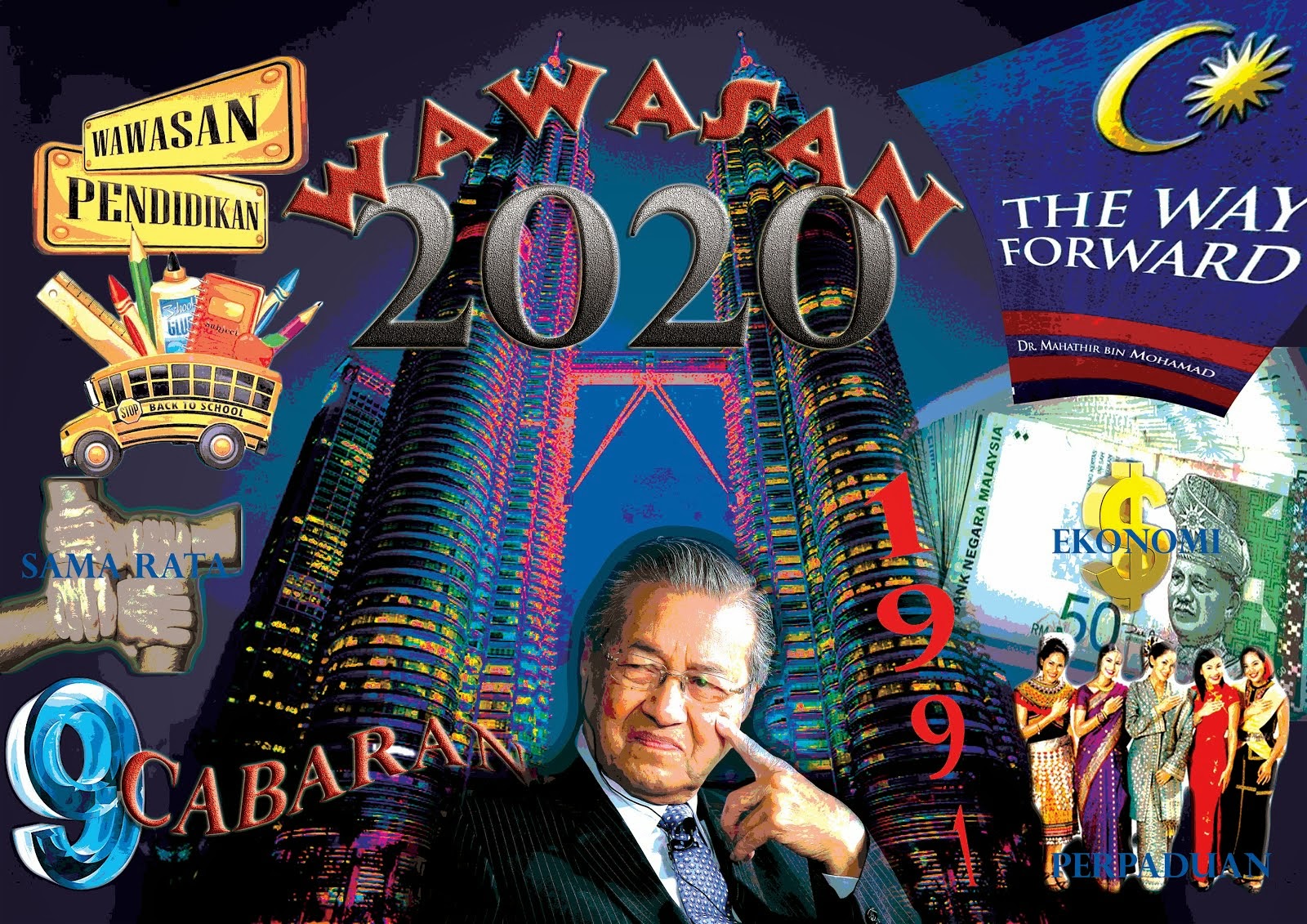

At one time, Malayan labourers helped make half of the world’s rubber

In 1920, Malaya supplied MORE THAN HALF of the world’s rubber! If you can recall your sejarah, much of the plantation community were South Indians (Tamils mostly) who came here during the British colonial era to work on coffee, sugar and rubber plantations, and to build infrastructure such as ports, roads and railways.

To keep up with the need for higher rubber production, they needed more manpower. They couldn’t convince the Malay community to join this industry (because they’re already farming and fishing) and needed to keep good relations with the Malay rulers.

And they couldn’t ask the Chinese community either because they were already running businesses and being recruited for tin mining. So they chose the Tamil labourers to do some repetitive and tedious work in the rubber estates.

The Tamils were also recruited as civil servants and plantation supervisors. So that’s how we got our Tamil plantation workers.

Prang Besar was one of the estates in question. Established by British officers who were granted some jungle land for rubber planting after World War 1, the estate company was named Prang Besar Estate Ltd to commemorate the Great War they fought in. It became the pioneer of the rubber estate industry in Malaya, which was one of the twin pillars of the economy from which today’s Malaysia prospered.

But the success of the rubber estates didn’t last long as the plantation workers later lost their jobs in the 90s, for 2 main reasons. One was reduced demand for their labour mainly becos of mechanisation and the shift from rubber to (less labour-intensive) oil palm. Another was plantations were bought to be used for urban expansion. And part of this urban expansion was none other than Putrajaya..

And plantation workers were given less than 2 months to vacate

Putrajaya, named after Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra (and combined with “jaya” to refer to success), was built as part of the Mahathir-led govt’s Vision 2020 plans and to also serve as the country’s administrative centre.

In order to do that, the govt peeps needed a workplace that was free from traffic jams such as those found in KL and also to be housed in one location. As mentioned in another CILISOS article, KL in the 90s was getting so congested, so the govt decided to move elsewhere to avoid the jam. After some shortlisting of possible sites, Prang Besar was chosen for 3 reasons:

- It’s near the new highway and airport connection.

- Prang Besar was under one estate, so acquiring the land was easier and cheaper.

- The North-South corridor gave an opportunity for expansion.

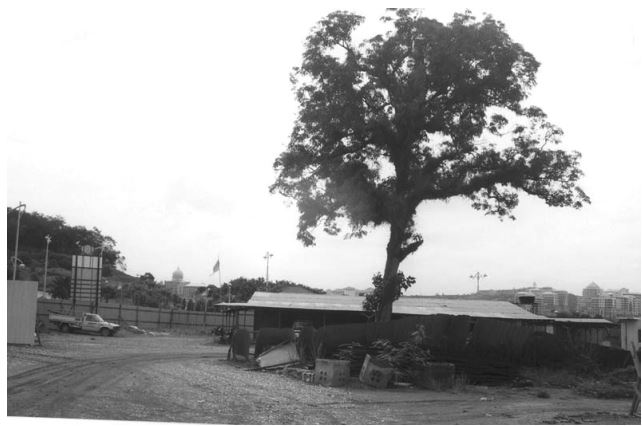

So, in August 1995, construction work of this city started. Plantation workers were given eviction notices by Putrajaya Holdings to pack up and leave within 48 days, while the plantations where they earned their living were destroyed.

This immediately resulted in losses of jobs, homes and temples for about 400 families from 4 estates (177 of whom were from Prang Besar, the biggest estate of the four). It’s also been said that some of the families lost their land, which they bought to rear cattle and cultivate veggies as early as 1975.

Imagine if you were asked to leave your house, your neighbourhood and your job, within 48 days.

Because they lost their lands, they had difficulties covering their rising living costs after moving

The parties that were supposed to help the workers.. didn’t help. The National Union of Plantation Workers (NUPW) was reportedly weak and ineffective, partly because of restrictive labour laws. The Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) also allegedly didn’t help, partly because of its junior position within Barisan. But NUPW and MIC also allegedly shook hands with plantation companies, property developers and the state govt to evict the workers.

So where could they go? The Putrajaya Master Plan included some 10,000 low-cost housing units. But, their location in Putrajaya and the quality of the units was, umm, uncertain, apart from being “world-class” and “wired“. The govt initially made it mandatory for developers to build at least 30% “low-cost” units (not more than RM25,000) in all housing projects.

But it looks like the ex-workers were not “rewarded” with any such units in the city (or in the words of the ex-workers, “kuppai mathiri thooki poddangga”, which means “thrown like rubbish”). In fact, they were moved to the Taman Permata flats in nearby Dengkil.

But why no place for them in Putrajaya itself? Apparently, the 10,000 supposed “low-cost” units were priced at RM49,000! It was not affordable enough. Not only that, it turns out that the ex-workers were told that this move was just temporary.

“They said they would give us terrace houses, and then gave us these flats to live in. They told us it was only temporary. The whole thing was done through word of mouth, nothing was in black in white. In those days, it was how things were done.” – said former Prang Besar estate worker K. Ramadass.

Before the displacement, the workers owned land that they could use for agriculture and farming for their own use and for extra household income. But this changed when they lost their land and did not have any land to own at the flats, so their extra income and savings were gone.

So to sustain their living, they had to get jobs.. in Putrajaya itself.

Since they’ve been in the agricultural sector for years, they didn’t have the necessary skills for the techy jobs that the skilled professional Indian nationals were attracted to. So most of them work as general workers such as security guards, cleaners, landscape gardeners, operator workers, truck drivers etc, which reap low income (ex: landscaping work paying around RM700 per month), resulting in low standards of living.

In fact, their income didn’t increase enough to meet the rising living costs, and although no ex-plantation worker is a stranger to hard work or poor pay, the other things that were provided for free in the estates were no longer free (like food crops that peeps could just pluck from).

“Some of the old fruit trees in Sedgeley estate were apparently still there but a former resident complained that when he went back to collect fruit, guards asked ‘who are you?’ and chased him away.” – plucked from “From the Margins to Centre Stage: ‘Indian’ Demonstration Effects in Malaysia’s Political Landscape” by Bunnell, Nagarajan and Willford.

Plus, the compensation given, ranging from RM4,000 to RM28,000, was not enough to match their years of efforts and were used up to repay loans for the flats. The very flats that’s been subjecting them to a bunch of safety and health issues, like that time in 2013 when the flat residents had to live in tents in the carpark after the Sepang Municipal Council declared the flats unsafe to live in, since their units had cracks, unstable foundations and wall decay.

“Every time it rains, the place floods. It is very difficult to stay here. There are a lot of mosquitoes at night. It is hard to sleep here, but I don’t feel safe sleeping in the flat. There is cement falling all the time.” – said ex-worker C.K. Mathavi.

The secretary of the Taman Permata Dengkil Residents Association, N. Kumaran said that the federal govt gave a check for RM2.5million in 2012 to maintain the place, but all that was done was paint the place. No fixing pipes or any work of that sort.

But wait… there’s still hope for this community, since the federal govt has taken steps to address this problem.

In fact, not all hope is lost, thanks to… our ex-PM Najib?

Although Najib has done some things in the past that made him lose some support and maybe lose himself, there was something he did that we could pat his back for. According to the Unit for the Socioeconomic Development of the Indian Community (Sedic), Najib’s govt made a 10-year plan to improve the quality of life for Malaysian Indians through the Malaysian Indian Blueprint (MIB).

One of the plans under MIB is to work on resettling the families to new homes and providing facilities for the ageing estate workers, allocating RM60 million to build 400 single-storey terrace houses in Ampar Tenang, Sepang with land provided by the state govt.

When the community heard about this in March 2018, they were HAAAAPPPPYYYYY! They can finally look forward to moving into their new homes, perhaps by July this year according to the noticeboard outside the construction site.

As the community awaits a better life in the future, some would suggest some measures to prevent this problem from repeating. When planning an urban development project, the developers are advised to consider the potential impact of the project towards those who currently reside in the area.

In this case, it would be involving the plantation community in the planning stages to get their voices heard, so that better arrangements that benefit both developer and community can be made. Now this responsibility of looking after the needs and rights of the Indian community has been handed to our current PH govt. While the previous administration has made many promises, perhaps this is one promise the current administration might consider keeping.

- 3.6KShares

- Facebook3.4K

- Twitter27

- LinkedIn17

- Email18

- WhatsApp136