The Orang Asli village rocked by 14 mysterious deaths has an odd way of burying the dead

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn8

- Email8

- WhatsApp40

[This article was originally written by SOSCILI. To read this article in BM, click here!]

Kelantan’s back in the news again, and sadly not for good reasons.

The state has become home to a number of unexplained Orang Asli deaths. Eighteen bodies – an original fourteen followed by another four – were found dead of a mysterious illness in the past couple of weeks, with another eight others unaccounted for still. Meanwhile, dozens of Orang Asli remain in hospital following the disease breakout. Deputy Prime Minister Dr Wan Azizah has also chaired an emergency meeting to discuss the issue.

Mesyuarat tergempar bincang perkembangan terkini situasi Orang Asli Kuala Koh

Perkara melibatkan nyawa rakyat adalah isu besar yang perlu perhatian khusus & tindakan menyeluruh

Setiap agensi terlibat akan memastikan isu ini ditangani sebaik mungkin demi kesejahteraan rakyat pic.twitter.com/00Qri0xEVy

— Dr Wan Azizah Ismail (@drwanazizah) June 11, 2019

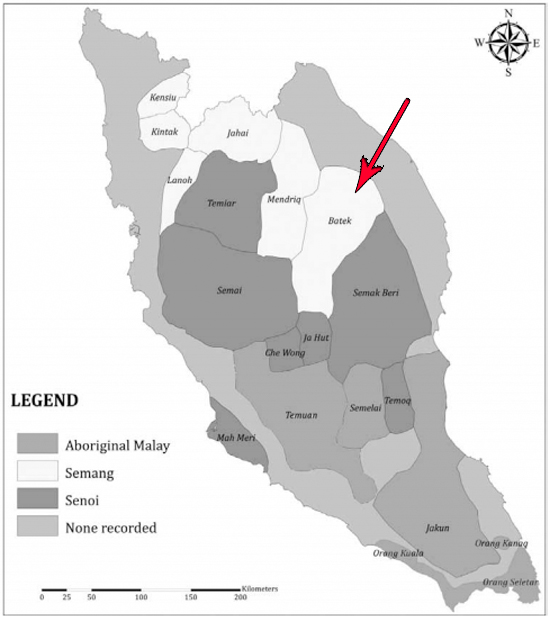

This article however, won’t be looking at the mysterious deaths. Instead, we would be taking a glimpse at the Orang Asli group affected by the sudden illness – the Batek people, sometimes also known as the Bateq people.

One of the 19 recognised indigenous groups in Malaysia, their population numbers just below 1,500 and live traditional nomadic lives. And while some of us urban folk can’t think of living just a day without our smartphones, for the Batek, their cultures and customs have remained the same for generations.

1. The Batek have been living in Malaysia for 100,000 years

The Batek folk originate from the Negrito aboriginals who have been in Malaysia for over 100,000 years. It’s believed that they came from the Indo-China regions by walking thru the mountains before reaching and living here. While the Negrito people never had a totally fixed location where they lived in, once the Batek people came about, they live mostly in the eastern half of the peninsular, staying mostly in Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang.

While they are a nomadic group – meaning that they often move around without a fixed home – the Batek do try and stay fixed during the monsoon season from Oct to January due to the danger of sudden floods. Being called the last of Malaysia’s nomadic Orang Asli groups aside, their day-to-day life is also pretty different from other indigenous groups.

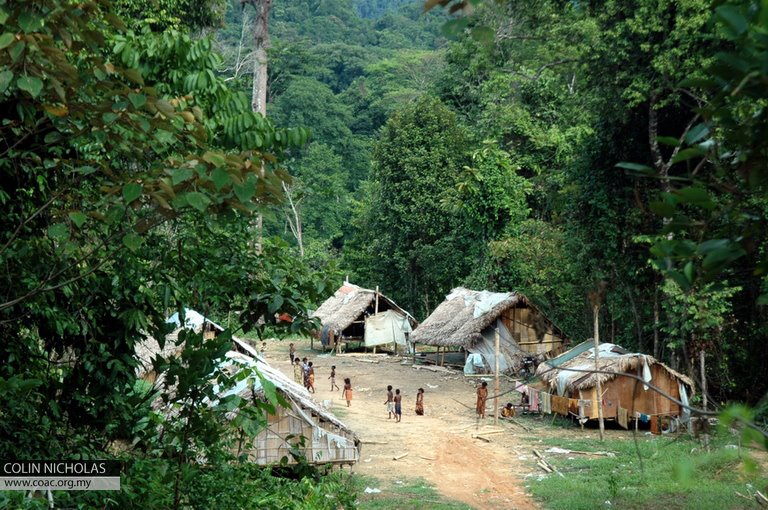

For a start, their ‘houses’ are very different from your shiny new PJ bungalow or even the typical stilt houses found in other Orang Asli communities. Made from whatever nature gives them, the Batek people would furnish it with leaves for roofs and sometimes even their own clothes for doors and curtains. These houses are often simple as due to their nomadic livelihood, it makes it easy to pack up and move and rebuilt again at their new home.

As for food, they hunt using blowdarts and poison arrows, with each Batek child given a blowpipe once they are deemed an adult. Once they hunt and gather their food, it’s time to cook. But while most other indigenous groups have probably gone on to use gas stoves, for the Batek, they remain using traditional methods for starting fires. This includes using rotan and meranti wood, rubbing them together to create friction for a fire – Bear Grylls eat your heart out.

2. The Batek are shy and seldom mingle with ‘foreign’ people

The Batek community in Kuala Koh – the ones in the news for the mysterious deaths – are only about 150 people strong. Like, most condos or apartments have more than 150 people in them! And even then the Kuala Koh village mostly comprises of just relatives of each other. But of course that’s not just the only Batek village laa; like we said earlier, there’s roughly 1,500 Batek people living in Malaysia. Most of these people live in small groups in various places.

Because the Batek people live in such small communities and far away from most ‘modern’ civilization, it’s said that most of them are shy and that it’s hard for them to interact with people foreign to them, such as tourists and govt officials visiting them. Apparently, when these super small villages get a visitor, the kids and women all start hiding in their houses like when your coworkers when the boss asks for a volunteer.

But not all of them are like that laa. There’s actually a decently sized Batek community living in the protected areas of Taman Negara, and with such unique cultures (plus the fact that their villages are hard to come by), this particular group often gets a number of tourists visiting them, some to learn more about their culture, and some even to make documentaries on them!

Here, when tourists come by, they are often greeted by the Batek villagers with vintage Malaysian hospitality. They would take their time to showcase their traditional skillsets to the eager eyes of the visitors. However, a fair warning to those who are planning to visit them: don’t stay too long yeah, cos they too want to rest after teaching mat sallehs how to blowpipe and what not.

3. They don’t know how money works, and instead depend on nature

For a group of people known as ‘nomadic hunter-gathers‘, it’s perhaps kinda obvious that the Batek are, well, heavily dependent on nature. Even when choosing a new place to move to, these jungle experts often pick a place near a river. This lets them forage the nearby forests while also able to move quickly using a raft on the river.

For villages that have tourists popping by every now and then, these visitors do somewhat contribute to their sustenance. According to Sena, the Batek community leader, the villagers would sometimes make traditional wristbands and necklaces which would be sold to these tourists.

“When tourists come we show them our traditional ways of starting fires and hunting with blowdarts. The women meanwhile make wristbands and necklaces from rattan and bamboo which would then be sold to the tourists. Sometimes this gets us up to RM200, which we can use for up to two months,” – Sena, Batek Tok Batin, translated from Projek MM

Despite that, because the Batek don’t often interact with outsiders beyond the tourists who visit them, some in the community seldom realise the significance of the cash they’re holding, leading to them commonly being conned.

“Most of the Batek don’t know how to count money… some have even paid RM100 for one sack of rice and didn’t get their change back. They often get cheated but what to do, we don’t know how to count,” – Sena, Batek Tok Batin, translated from Projek MM

Nevertheless, this never changed the Batek nor do they hold hard feelings. According to Sena, the community is used to it and that there’s bound to be ups and downs anyway. Even if they moved to the city, there would be no income for them, plus higher living costs too.

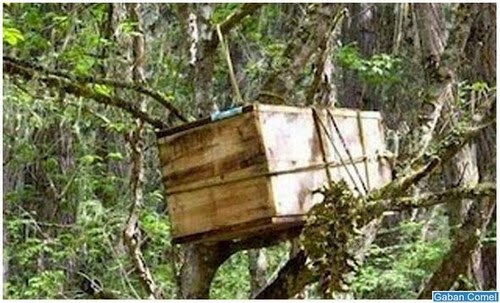

4. Dead Batek people aren’t buried, but instead left in a treehouse

Almost everyone will tell you that there the two biggest events in anyone’s life are more often than not marriage and death, and it’s kinda the same for the Batek.

For marriage, when a couple comes two-gether (#pungamestronk), there will be some tests before they can become a married pair. For the groom, they will be tested on their blowing skills… on the blowpipe. This is cos the blowpipe is the main tool for the Batek during hunts. The groom’s blowpipe skills will be gauged by the village chief, and if he passes, the couple will then move on to stage two of the tests.

This time, the couple will be left to spend the night together. If either the bride or groom leaves the room, the marriage will be cancelled. This simple test is just to see if both are loyal to each other – but usually loyal laa, with Batek folk never remarrying if their partner passes away.

As for whenever a village member passes away, the Batek poeple don’t bury them six feet under nor do they cremate the dead. Instead, they place them in huts or coffins that are built on trees, 40 meters high. They then cover the body with leaves before leaving the area altogether and moving to a new camp ground. After a couple of years, the community would sometimes come back to their old stomping ground. If the bones of the deceased fall to the ground instead of remaining up on the treehuts, the Batek see this as a sign that the deceased had sinned during their lifetime.

There’s a fine line between preserving culture and protecting people

While all this culture is indeed fascinating and should be recorded by our historians, there’s still a need to also protect the welfare of the Batek people. Reports of the Batek people avoiding medical treatment isn’t helping doctors and authorities track down the cause of the mysterious disease, and in fact the health problems that the Orang Asli face have been going on for decades. But at the same time, moving them out of their nomadic lives and into resettlements might be too extreme and lead to the demise of the Batek people’s culture as we know it.

As such, the authorities perhaps have the unenviable yet important task of saving both the Batek people without risking the heritage and culture that come with them.

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn8

- Email8

- WhatsApp40