The origins of Na Tuk Kong, a “Malay” deity worshipped by the Chinese

- 3.0KShares

- Facebook2.7K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn10

- Email12

- WhatsApp158

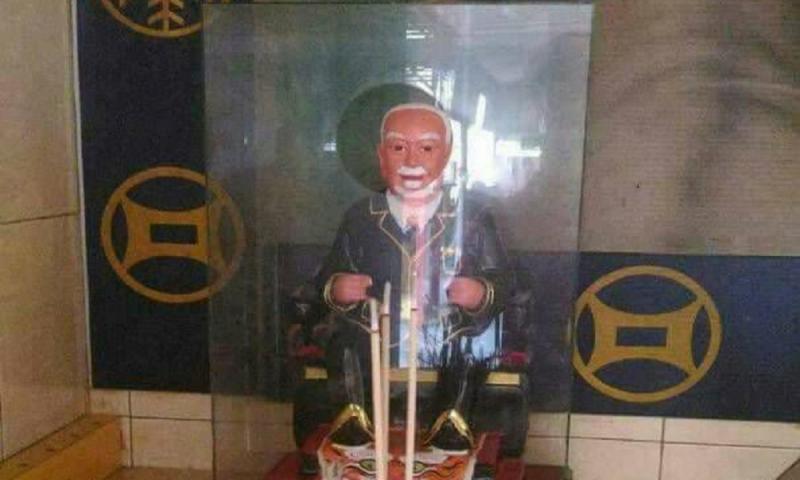

Ya’ll ever seen these shrines by the roadside, near housing areas, or even commercial buildings? Of course you have. You might even know that the deity that’s sat in these shrines is called “Na Tuk Kong” or “Datuk Gong”.

Yes, the shrines have Chinese-esque designs, and the worshippers are almost exclusively Chinese, but what you might not have known is that the deity is as much Malay as it is Chinese. If you look a little closer at some of the sculptures of Na Tuk Kong, you’ll notice that they’ve got Malay features. Y’all probably have some questions right about now: why do some Na Tuk Kongs wear traditional Malay clothes? Are Chinese people reaaaally worshipping a Malay deity? Who’s Na Tuk Kong anyway?

Well…

Na Tuk Kong came from a blend of ancient Chinese and Malay customs

Na Tuk Kong goes way back – he’s been worshipped in Malaysia as a guardian deity of peace, prosperity, and health since the early 19th century. The concept of Na Tuk Kong actually came from China – the mainland Chinese have long worshipped “Tu Di Gong” (God of the Earth in Mandarin), a deity in charge of the wellbeing of the residents in a locale. When the Chinese migrated over to the Southeast Asian region at the beginning of the 19th century, they brought with them their customs, traditions and practices – including Tu Di Gong.

At the time, the local Malay community were into animism and the worship of “Datuk Keramat”, a collection of pious men, preachers of Islam and leaders of Islamic movements believed to hold semi-divine powers.

The interactions between the Chinese and the Malay in Malaysia have provided a platform for the Datuk Keramat worship to be accepted by the Chinese Malaysian. The Datuk Keramat concept is accepted and was later pronounced as Datuk Gong by the Chinese. The ‘Datuk’ in the Datuk Gong concept is the Datuk Keramat. ‘Gong’ is an honorific title attached to Chinese deities. – Dr. Lee Yok Fee, researcher for Universiti Putra Malaysia

Basically, what happened was the migrant Chinese needed a deity like Tu Di Gong to watch over them in their newfound home (it’s not like Tu Di Gong could’ve just hopped on an AirAsia flight), and saw that the whole Datuk Keramat thing was similar to what they’ve been doing, so an amalgamation of sorts happened, leading to the creation of the Na Tuk Kong.

Some Na Tuk Kongs could have once been real live Malay people

It’s really not as weird as it sounds, we promise. In the olden days, it’s supposedly possible for people who have contributed a lot to their local community or performed amazing feats when they were alive to be deified. A good example here would be Guan Yu (shoutout to Dynasty Warriors Fans), a Chinese general who served under the warlord Liu Bei during the Three Kingdoms period in China. The man’s martial prowess was so staggering that people started worshipping him as a deity after his death. Interestingly, in Hong Kong, an altar dedicated to the bearded warrior can be found in every police station… and ironically, in many triad hideouts as well.

That’s probably what happened with certain Na Tuk Kongs in Malaysia – Mr. Ng, former chairman of Teluk Intan Datuk Gong’s temple certainly thought so. In an interview with researchers from Universiti Putra Malaysia, he said that the Na Tuk Kong had to have been a local person cuz they were recognized for their contributions to their community here in Malaysia. Plus, many Na Tuk Kong effigies sport tengkoloks, sampins, kopiahs or kerises (what the hell is the plural of “keris”, anyway?).

In fact, a Na Tuk Gong temple in Banting, Selangor plays host to a Sultan Na Tuk Gong. No, he’s not the Sultan of Na Tuk Gongs. Chinese Bantingites over a hundred years ago started worshipping Sultan Abdul Samad as a Na Tuk Gong, and we’re not quite sure why. Maybe it was because he started trading tin with the states of the Straits Settlements, which attracted even more Chinese miners to Malaysia. Maybe it was because he helped found the prestigious Victoria Institution. Seems like no one really knows.

What we do know is the kind of offerings that Na Tuk Kongs prefer…

You can only serve halal food to certain Na Tuk Kongs…?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erc9ptMAl7o

While practices differ from place to place, many believe that Malay Na Tuk Kongs should only be served halal food since Islam forbids the consumption of pork. Take for instance the Na Tuk Gong Dan (festival commemorating Na Tuk Kong’s birthday) celebrated by the residents of Desa Aman Puri, as described in this research paper from 2014.

Worshippers from the area were reported to be “cautious” in deciding their Na Tuk Kong’s menu – halal foods like chicken curry, mutton curry, kopi-O, betel leaves and nasi pulut kuning were served to celebrate the deity’s birthday. Apparently, people even offered the Datuk some cigarettes. It’s said that whoever that fails to do so would incur the wrath of the Na Tuk Kong, and they’d be stricken with bad luck for a little while.

In contrast, non-Malay Na Tuk Kongs are perfectly okay with non-halal offerings, like pork and alcohol. A side note here: non-Malay Na Tuk Kongs don’t only consist of Chinese variants; there’s a Siamese Na Tuk Kong (one resides in the Kampung Sawa Datuk Gong Temple in Lenggong, Perak, and amazingly, a Karpal Singh Na Tuk Kong in Teluk Intan, Perak.

Having said all that, what’s the takeaway?

Na Tuk Kong was only possible because of a melting pot of cultures

Despite instances in the past where shrines have been destroyed for assorted reasons, the practice of Na Tuk Kong worship is still going strong in Malaysia – as a matter of fact, there were wholesome stories of local authorities preventing ne’er-do-wells from wrecking some of these religious sites. That really says something about Malaysians accepting the differences we have and embracing the melting pot of cultures that only serves to enrich our culture as a whole.

Funnily enough, the Na Tuk Kong is worshipped in many countries in the Southeast Asian region, including Singapore, Brunei, Southern Thailand, and Indonesia, but the practice never made it back to China where it originated from.

- 3.0KShares

- Facebook2.7K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn10

- Email12

- WhatsApp158