The sad fate of Penang’s pre-war Japanese prostitutes, the karayuki-san

- 2.9KShares

- Facebook2.7K

- Twitter19

- LinkedIn19

- Email32

- WhatsApp190

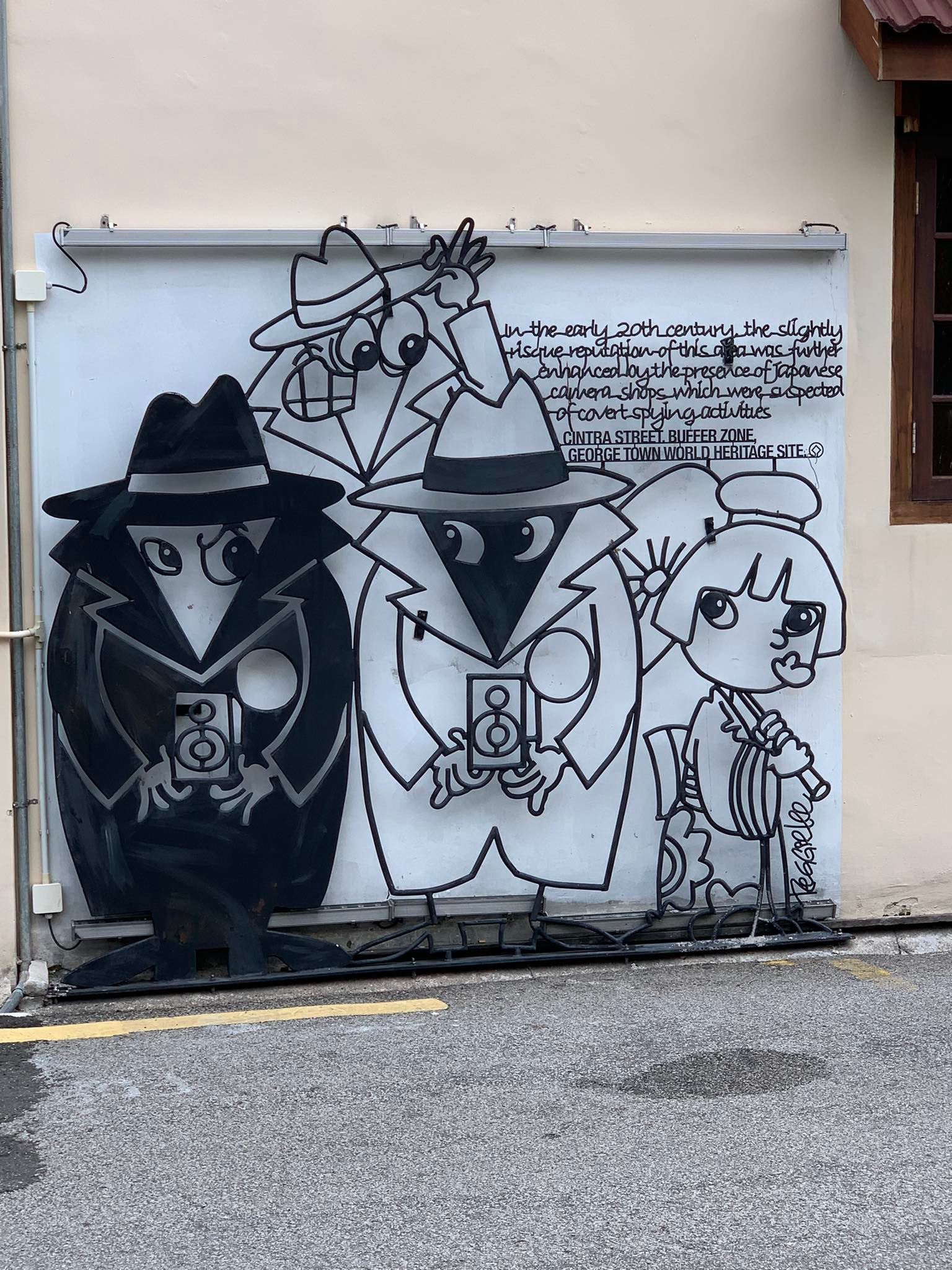

Nowadays, Cintra Street in Penang is a popular tourist attraction with its charming guesthouses and old-school architecture. Known for its booming textile and gold trade in the 1960s-1980s, it’s arguably one of those places that defines Penang as a quintessentially Malaysian historical location.

However, beneath the charm and well-maintained shoplots lies a dark past, as Cintra Street was once famously known as the red light district of Penang. And within those walls lay the tragic story of the karayuki-san, or Japanese prostitutes, who plied their trade in and around the area during the late 19th-early 20th century.

But who were these women, and how did they end up so far from home in such harsh conditions? Well, to understand that, we have to go wayyy back, to the Edo Period (1603 – 1867) in feudal Japan…

It all started on Kyushu Island with the two Ts: Taxes and Torture

When Matsukura Katsuie, the pro-Tokugawa daimyo (feudal lord) of Shimabara started torturing Christians and taxing his people pretty much to starvation to raise funds for his fancy castle, the people of Kyushu revolted; sparking the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-38. Although Katsuie eventually suppressed the rebellion, he himself was later executed by the Tokugawa shogunate cos, well, he really was kind of a jerk.

The severe depopulation on the peninsula caused by the fighting meant that Katsuie’s replacement, Kōriki Tadafusa had to flood the area with immigrants to stimulate the economy, with the Tokugawa choosing to blame the Christians rather than the over-taxation for the whole fiasco.

Fast forward to the Meiji Period (1868-1912), and things did not improve – fishermen and peasants in the region were still being taxed 50% of their annual harvests, as well having to pay an additional tax on female children (leading to a rise in female infanticide). Furthermore, immigration had severely limited work opportunities.

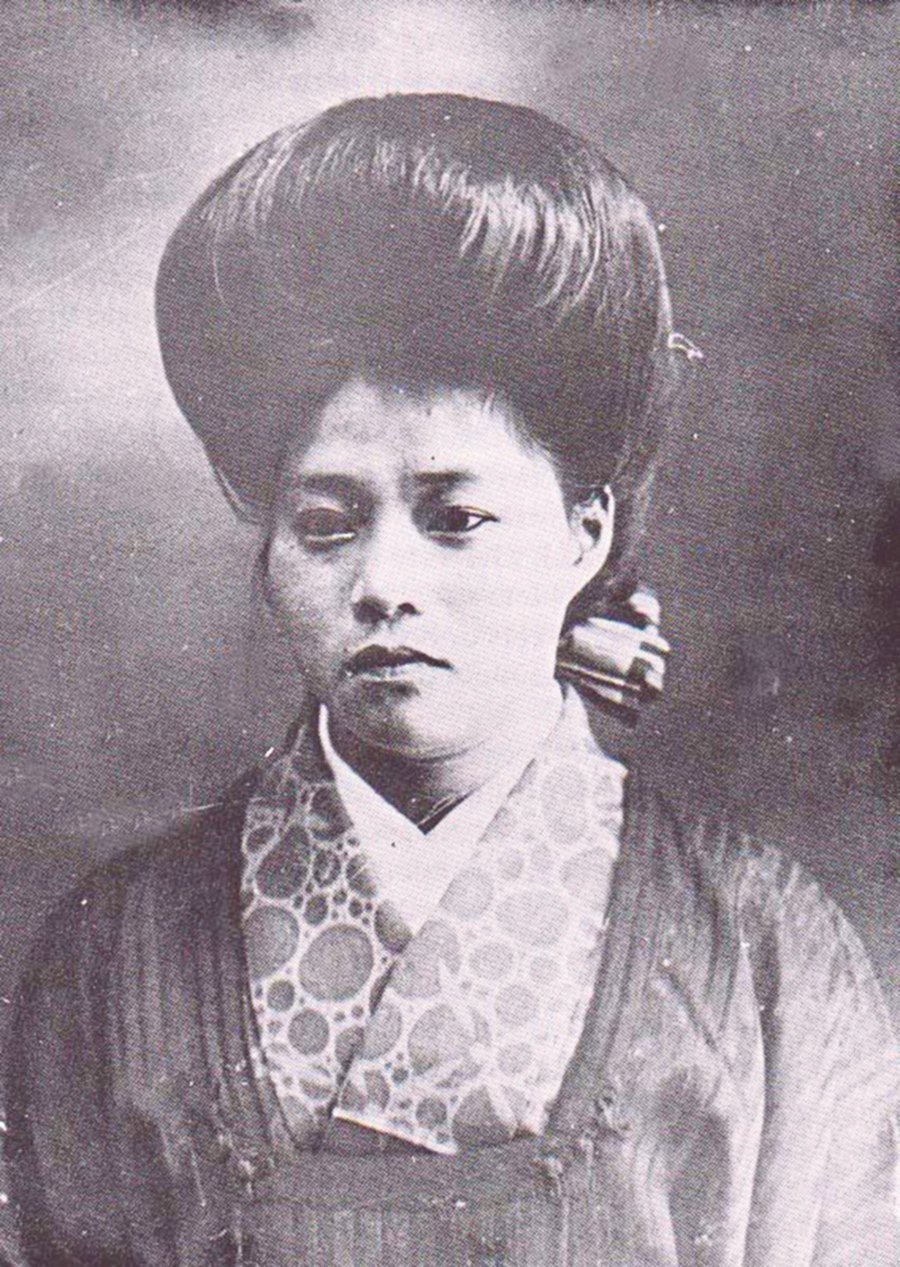

With the threat of famine on the horizon, many had no choice but to sell their daughters overseas as prostitutes, or ‘karayuki-san’, meaning ‘Miss Gone-To-China/Miss Gone Abroad’.

Karayuki-san were a major source of capital for Japanese businesses in Penang

The fates of karayuki-san back then were not so different from those of today’s sex workers: they were often duped by offers of waitress jobs or money-lending schemes, before being forced into the sex trade, some to places as remote as Zanzibar or Siberia. Some were even lured under the pretext of patriotism, convinced that they were the equivalent of female soldiers serving for the good of Japan. Despite their tough circumstances, karayuki-san would send money home to help their impoverished families.

In 1910, there were an estimated 207 Japanese citizens in Penang in 1910; half of whom were in the sex trade, usually operating out of geisha houses in the areas of Cintra Street, Kampung Malabar, and Campbell Street. However, the bulk of the income made from the karayuki-san sex trade would go on to fund legitimate Japanese businesses in Penang such as medicine, dentistry, hotels, and photography.

Such was the impact of the Japanese economic boom in Penang at the time that Cintra Street came to be known as Little Japan, or Jipun Sin Lor (‘Japanese New Road’). In fact, even today, some Chinese-Penangites still refer to Cintra Street as ‘Jipun Kay’, with the Hokkien word ‘kay’ actually being a pun, as it can mean either ‘road’ or ‘chicken (prostitute)’, depending on the intonation.

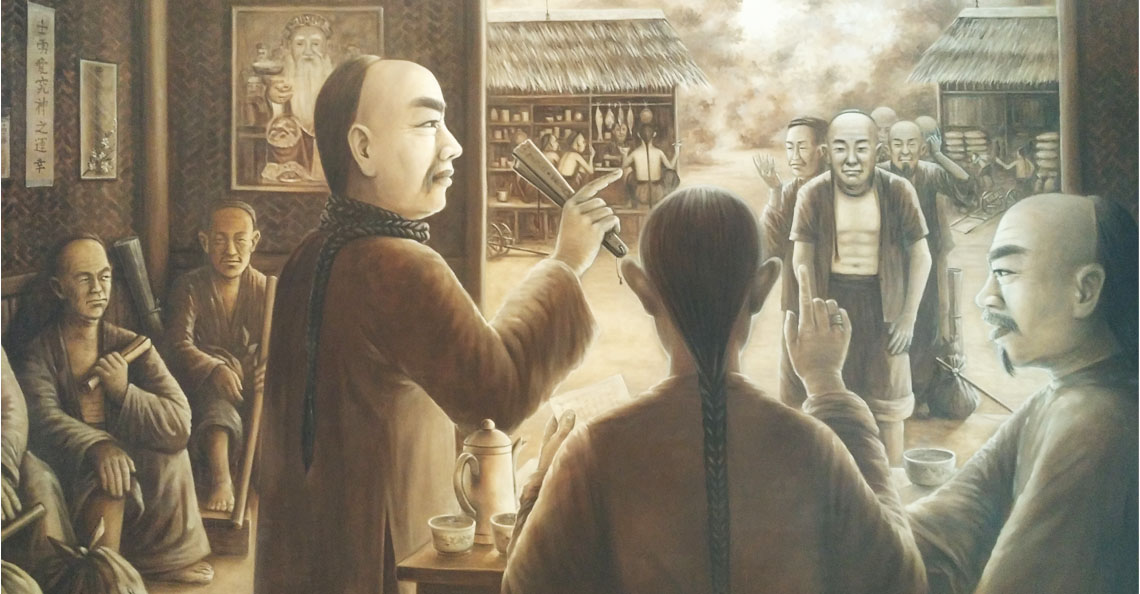

Although in competition with Chinese prostitutes in the area (‘Sin Kay’), Karayuki-san were preferred by foreigners and non-Chinese as they did not turn away foreigners as the Chinese prostitutes did, underwent strict hygiene inspections, and were skilled at hospitality and performing arts:

“The houses of pleasure were identified by red lanterns hung at the door. Senior citizens recall these dens as places to relax and enjoy a range of services… The well-dressed, well-mannered courtesans served opium, tea and liquor, and provided musical entertainment and companionship.” – Khoo Salma Nasution, Penang Heritage Trust

But on the darker side of things, it was not uncommon to find prostitutes as young as 10 or 11, sometimes sold off by their mothers or grandmothers for as little as £10 and being ‘rented’ to customers for around $150-$500 depending on the women’s age, virginity, beauty, and origin. These women were treated as little more than commodities, and would be transported from town to town to earn their living.

In the 1920s, the Japanese saw karayuki-san as a source of shame

With the rise of Japanese nationalism, especially after their victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, karayuki-san began to be seen as a disgrace by the Japanese. Working with the British administration, the Japanese government moved to abolish karayuki-san across the globe, repatriating many of them back to Japan, unfortunately exposing them to severe discrimination back home.

Some ended up marrying locals, or even moved underground to continue the sex trade. By World War II, the karayuki-san had all but disappeared from Penang, with the few remaining ones becoming mistresses to ex-clients or cafe/restaurant waitresses in George Town, arguably enjoying a better fate than those who chose to return to Japan.

But many karayuki-san ended up dying on the job, often from disease. There is a Japanese cemetery on Jalan P. Ramlee which serves as the final resting place for many Meiji-era karayuki-san, who make up the majority of the dead interned there. However, not every karayuki-san was lucky enough to have a tombstone in their name; in the book Sandakan Brothel No. 8, it is said that some who died in Sandakan, Sabah, are buried in nameless graves on the hillside, totally fading from history and memory once their crude grave markers rot away.

It is perhaps a small consolation to the dead karayuki-san that the Japanese people still honor their sacrifices today. In Kyushu, there is a monument dedicated to their memory, with hundreds of stone fence posts inscribed with their names, contributions, and places of occupation which include Penang, Singapore, Ipoh, Rangoon, and Siberia.

- 2.9KShares

- Facebook2.7K

- Twitter19

- LinkedIn19

- Email32

- WhatsApp190