The Sultan who helped the Brits gain power in 1870s Malaya…also allegedly killed a Brit

- 3.1KShares

- Facebook2.9K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn21

- Email26

- WhatsApp151

If you remember anything from our buku teks Sejarah, you’ll probably remember an angmoh named JWW Birch, who was the first British resident in Perak. You’ll probably also remember how he ended up getting assassinated by a group of Malay chiefs.

The man credited for Birch’s murder was a Malay chief called Majaraja Lela, who masterminded the assassination. And apparently, the assassination sparked an inspiration for later generations to rebel against colonial powers, so Maharaja Lela kinda became some sort of heroic figure.

But there’s one thing you might not know in this whole saga – maybe because his name only turned up as a footnote in our textbooks – was that the Perak ruler at the time, Sultan Abdullah, was allegedly involved in the coup as well!

Holy cow! How come? Well…

It’s claimed that Sultan Abdullah gave permission to murder Birch

Just to refresh your memory a bit, Birch was depicted as a not-very-popular person among the Perakians, mainly because he wanted to swiftly change things in Perak to make it seem ‘British’. Not just that, he also seemed to appear not all that understanding towards local customs, probably because he didn’t know how to speak the local language at all.

Furthermore, he wanted to take away the rights of Malay chiefs to collect taxes, while also, um, abolishing slavery locally as he didn’t understand why a custom like that existed. You see, slavery was sadly a common thing back then, and it was even said that the local Malay population had Orang Asli slaves in the 1800s. So naturally, that kinda riled up the Malay chiefs…and Sultan Abdullah.

“I will never acknowledge the authority of Mr. Birch or the white men.” – Maharaja Lela in 1875, as quoted from Sabrizain

So then, you know, the Malay chiefs decided that it was best to just…kill off Birch. And they did by stabbing him while he’s showering – yikes, he didn’t even drop soap wei. In the end, these Malay chiefs were all executed for their involvement.

Meanwhile, Sultan Abdullah came into the picture when he allegedly attended a meeting to discuss the assassination at a place called Durian Sebatang. In addition, it was said that that the Malay chiefs only proceeded with the assassination with the Sultan’s approval. He was also allegedly responsible for purchasing and providing the weapons required to kill Birch.

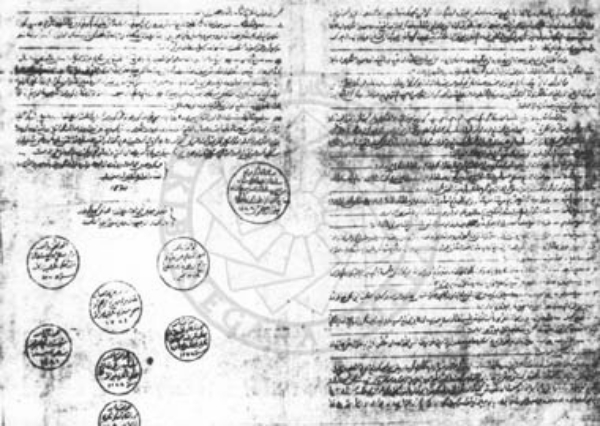

“The evidence… shows that for some time before the deed was committed you were conspiring with certain chiefs of Perak and other persons to effect that murder, and to drive Mr. Birch’s staff out of Perak, and that the murder of the British resident, and other outrageous therewith connected, were actually committed under your authority and with your assistance.” – Colonial secretary of the Straits Settlements in Singapore John Douglas in 1876, as quoted from SembangKuala

As such, Sultan Abdullah was charged too. However, unlike the Malay chiefs who were executed for their actions, he was only taken prisoner in Singapore, and then exiled to Seychelles in 1876. However, in an ironic twist…

Sultan Abdullah was the one who invited the British to Perak in the first place

Before Sultan Abdullah ascended the throne, Perak was ridden with Chinese gang wars, so serious that they even got their own names – the Larut Wars. The Larut Wars were a series of wars that started from 1861 and ended in 1874.

You see, at the time, a lot of people in Larut made their fortune through the tin mining business, and among those who had their hands in the tin mining pie were various Malay chiefs and Chinese secret societies Ghee Hin and Hai San. Well, they call themselves secret societies then, but we’ll better know them as Chinese gangs in the modern world – you know, when they have people like taikos and tend to use parangs to keng sou.

However, at the top of the tin mining food chain was a Malay fella called Ngah Ibrahim. He was the owner of the Larut territory and awarded tin mining leases to the Ghee Hin and Hai San gangs.

And these gangs brought along with them a long-running rivalry to gain control of the tin mining industry in Larut, triggering the beginning of the Larut Wars in 1861 and disrupting tin production and trade.

But as if the Chinese gang rivalry wasn’t enough, the Malay royalty somehow got into the feud as well when the Sultan at the time, Sultan Ali passed away in 1871. By right, his heir, Raja Abdullah – uh huh, the very same Abdullah – should inherit the throne, but the Perak chiefs installed Raja Ismail as the Sultan instead because Raja Abdullah was apparently weak and unpopular.

With his eyes still on the throne, Raja Abdullah apparently instigated a power struggle by siding with the Ghee Hin gang, while Sultan Ismail and Ngah Ibrahim sided with the Hai San gang. That escalated the Larut Wars from a rivalry between Chinese gangs to a matter of a power struggle between the Malay royals. Things got so bad that Raja Abdullah apparently decided to pen a letter to the Straits Settlement governor at the time, Andrew Clarke, in 1873, asking him to intervene.

Upon receiving the letter, Clarke took the opportunity to gather all the involved parties, including Raja Abdullah and the Chinese gangs, to Pulau Pangkor for a round of discussion. At that very meeting, it was said that Raja Abdullah agreed to the presence of a British Resident as long as he was installed as the Sultan, which was naturally agreeable to Clarke.

Subsequently, the Pangkor Treaty of 1874 was drawn up, stipulating that Raja Abdullah would ascend the throne as Sultan and receive an advisor in the form of a British Resident. And yeah, you guessed it, the British Resident turned out to be JWW Birch. Sultan Ismail, who was notably absent from the discussion at Pangkor, was taken down and merely given a pension. The Larut Wars also kinda ended just like that.

And well, you know the rest of the story. Birch was largely disliked and he ended up getting cucuk while showering. As a result, Sultan Abdullah, who was implicated in his assassination, ended up getting exiled to the Seychelles.

Sultan Abdullah got un-exiled after 18 years

While he was technically an outlaw due to his exile, Sultan Abdullah apparently led a pretty decent life in Seychelles. For example, he became an avid sportsman, like crickets, soccer, and kite flying. He even joined the Victoria Cricket Club, playing with the likes of British military officers. He collected walking sticks and introduced some Malayan fruits to the Seychelles locals.

There’s even a story of how our national anthem, Negaraku, came about from his stay in Seychelles, and we even wrote an article about it, so we’re not gonna go too deep into that.

He remained in exile for 18 years and had maintained his innocence throughout, but it was the death of one of his wives in 1891 that might have become the last straw for him, it was said that Sultan Abdullah was deeply saddened by her death. So in 1891, he wrote a letter to his British friend, Sir Hennikon Heaton, who was the Canterbury MP at the time.

In this letter, Sultan Abdullah apparently talked about his sadness over the death of his wife and desire to return to his homeland.

“Before this sad event I have been deploring my situation as an exiled man; now I have to deplore the loss of my wife.” – Sultan Abdullah in 1891, as quoted from Seychelles Weekly

Sympathetic with the Sultan, Heaton allegedly strongly believed in Sultan Abdullah’s innocence and fought for his freedom, alongside other British officials who believed in him as well. We found a letter that seemed to confirm that Sultan Abdullah was allowed to return to Perak in the very same year, but for some reason, he didn’t return to Perak until 1894.

“I can leave Seychelles, but as soon as my arrangements present, I shall give Your Honor two months notice of the date of my intended departure.” – Sultan Abdullah in 1891, as quoted from SembangKuala

Sultan Abdullah only managed to enjoy life in Perak for 28 more years, as he subsequently passed away in 1922. While Sultan Abdullah might have been in exile for a large part of his life since the Larut Wars, it was believed that…

Sultan Abdullah’s actions had helped the British in colonial Malaya a lot

Before Sultan Abdullah reached out to Clarke during the Larut Wars, the British apparently mainly maintained a stance of non-intervention in local affairs, mainly Malay affairs, because they couldn’t find a legit reason to interfere in the first place. However, Sultan Abdullah’s letter to Clarke apparently turned out to be the perfect opportunity for them, due to the emergence of the Pangkor Treaty.

You may think that the Pangkor Treaty’s just a simple paper that had let Sultan Abdullah become, well, Sultan. It’s apparently something that played a large part in Malaysia’s colonial history, where it became a roadmap for the colonizers to actively intervene in other Malay states and brought them under British rule. Within a year after the Pangkor Treaty was signed with Sultan Abdullah, Clarke went ahead to install British advisors in three other Malay states.

We’re not saying that Sultan Abdullah was at fault for inviting British intervention in the first place, as many factors (*cough* British imperialism *cough*) played a part in what eventually became colonial Malaya. But perhaps we shouldn’t be too quick to dismiss Sultan Abdullah, as he’s a pretty significant part of our history – even if our Sejarah textbooks may not give him credit as such.

- 3.1KShares

- Facebook2.9K

- Twitter14

- LinkedIn21

- Email26

- WhatsApp151