This British officer fell in love with Malay culture… so he stayed back to protect it

- 2.4KShares

- Facebook2.3K

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn5

- Email9

- WhatsApp46

(Artikel asal dari Soscili. Klik sini untuk baca dalam BM.)

When we read about Mat Salleh in our Sejarah textbooks, it’s usually about the bad things they do.

For example, Form 5 Sejarah told us that there was this guy named J.W.W Birch who not only had no respect for local customs in Perak, but also tried to force Western customs on the locals (Here’s a different take on that story). We also learned that the British killed and paraded the body of Tok Janggut from Kelantan for opposing sistem penasihat British. Basically, the main takeaway we got from Sejarah is that the Brits and the Malayans didn’t always get along.

Yet, what if we tell you that there was actually one dude who loved the Malay culture so much that not only did he embrace it as his lifestyle, but he also left his own mark on it?

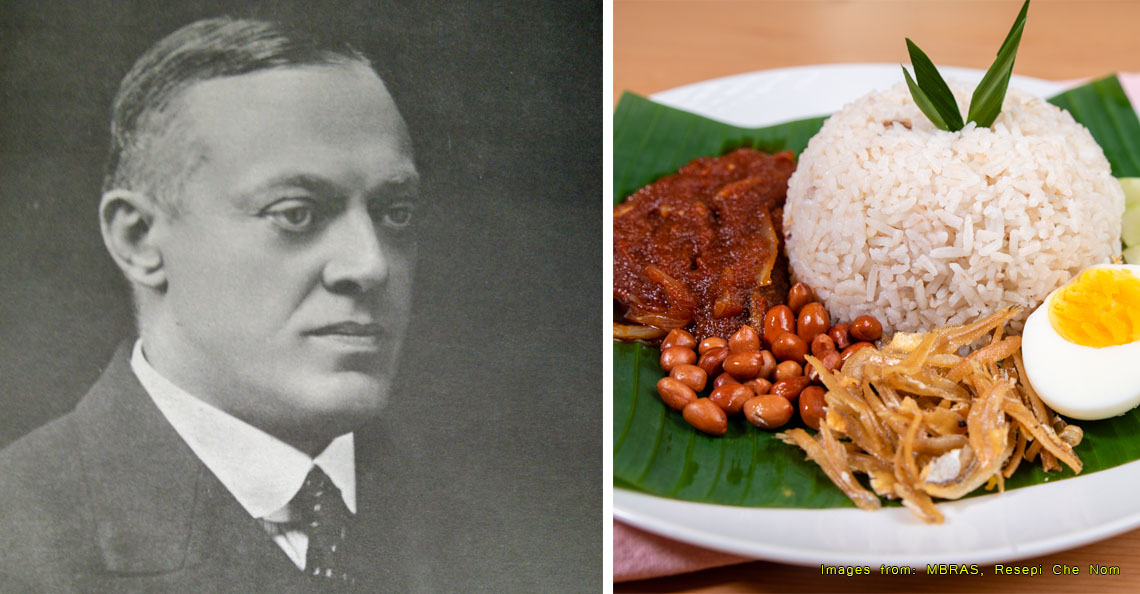

Meet Abdul Mubin Sheppard — The Nice British Officer

Born on 21 June 1905 in Ireland, Abdul Mubin Sheppard was born as Mervyn Cecil ffrank Sheppard (just in case you’re wondering, no there isn’t a typo. ff actually represented the capital F in Middle English!) Educated first at Marlborough College, he then went on to complete a degree in History at Magdalene College, University of Cambridge from 1923 to 1926.

After that, Mubin passed the Malayan Civil Services (MCS) Competitive Exam in London and was admitted into the MCS. The exam was first held to identify qualified candidates for the civil services in several British colonies, but it soon added to the prestige of these civil services and greatly attracted British graduates from top universities. Mubin would end up serving in the MCS until 1963.

When World War II broke out, Mubin served as a Company Commander for the Federated Malay States Volunteer Force for two years (1941 – 1942). In an unfortunate twist of fate, Mubin was held as a prisoner of war by the Japanese for three years until the Japanese surrendered in 1945.

Mubin returned to his service in the MCS after the War. He was appointed as the first Public Relations Director in 1946. 12 years later, he was appointed as the first Keeper of Public Records (now known as The National Archive of Malaysia). In 1959, he was appointed as the first Director of the National Museum of Malaya.

Mubin was very interested in preserving the Malay heritage, and this is informed by many of his contributions to it.

Mubin rewrote Malay literature in English.

Mubin was very inspired by a former British Resident in Malaya, Hugh Clifford, who wrote many books talking about both Malaya and the people there. He looked up to Clifford as his role model, and this informed his ambition to really immerse himself in the Malayan culture.

Witnessing the lack of hype in Malay literature among English readers, Mubin wrote and published a short story titled, ‘The Adventures of Hang Tuah’. Mubin chose to retell Hang Tuah’s story in particular because, in his own words, it has ‘a happy blend of history and romance’.

The translation of this literature was not a small feat because the original version was considered as heavy literature with its archaic Malay language and background context that might be hard for any non-Malay native to understand.

Instead of directly translating the whole book, Mubin chose to focus on and retell the ‘adventure’ side of Hang Tuah’s life only. He did so through using ‘Hikayat Hang Tuah’ and ‘Sejarah Melayu’ as his reference.

“This book was extremely popular because it had been published at least five times, and was used as English reading material in many schools. The fact that the book has been re-printed for so many times is perhaps a sign that this book has now become a common book.” – Prof Dr Muhammad Hj Salleh, extracted from his academic paper published in September 2003.

Mubin’s retelling of ‘Hikayat Hang Tuah’ also became the main source of inspiration for the movie on Hang Tuah later on.

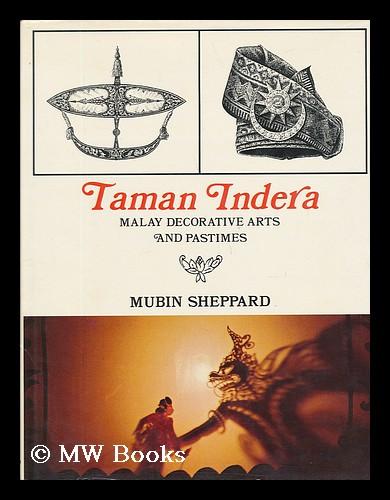

In addition to this book, Mubin had also published many other books covering Tanah Melayu, such as

- The Malay Regiment

- A Short History of Malaya

- A Short Biography of Sultan Abu Bakar of Pahang

- The Magic Kite and Other Ma’Yong Stories

- The Living Crafts of Malaysia, Tunku – His Life and Times

He saved many of our historical buildings.

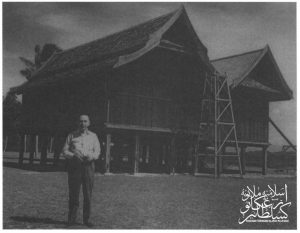

Mubin was deeply interested in doing historical conservation works, and this was reflected in his efforts to preserve and conserve some of the historical buildings here in Malaya. An example is the Ampang Tinggi Palace in Negeri Sembilan.

The Ampang Tinggi Palace was first constructed in 1865 by Yam Tuan Imam, the Yamtuan Besar of Negeri Sembilan. It was then presented as a wedding gift to his daughter, Tengku Chindai. After the last resident of the Palace, Tengku Halijah, died in 1921, the Palace was not inherited by anyone because she had no descendants. The building was initially lived in by several of his extended families before becoming completely abandoned after 1930.

20 years after its abandonment, Mubin visited the Palace and found it to be in a wretched state—it was infested with ticks and the rooftop had toppled.

“Sheppard requested permission from Tuanku Abdul Rahman (Yamtuan of Negeri Sembilan at that time) to be allowed to move the ruin and rebuild it as a State Museum.”

In January 1953, the building was dismantled by Malay carpenters and moved, plank by plank, to Seremban on a site chosen by Tuanku Abdul Rahman and his Chief Minister, Datuk Haji Abdul Malek. […]

Reconstruction was completed in March 1954 under the supervision of Mr Spence, the Public Works Department state engineer, who produced measured drawings of the building.

— Extract taken from Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Apart from the Palace, Mubin was also responsible for the restoration of Gedong Rajah Abdullah. The Gedong was initially built in 1857 to store weapons, tin ore, and food. What makes it unique is that it was the warehouse of the first Malay tin-mining pioneer in Malaya.

In 1980, there was a plan to demolish and convert the Gedong into badminton courts. Mubin protested against this plan so intensely, it eventually prompted the Selangor Sultan, Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah, to interfere. His fierce determination succeeded in saving the building, and it is now under the care of the Department of National Heritage.

Of course, these are not the only two buildings Mubin has helped preserve; some of these other buildings include the Kampung Laut Mosque in Kelantan and the Tengku Nik Palace in Terengganu.

He was a founder of PERKIM.

In 1957, Mubin made the decision to revert to Islam. He completed the Haj three years later, and was very active in dakwah since. When Tunku Abdul Rahman came up with an idea to establish a body that would help the underserved Muslim community, the first person that he called was Mubin Sheppard.

“He [Tunku] asked Mubin Sheppard to call several friends from different races for a meeting at his official residence at Brockman Road. At the evening meeting were SOK Ubaidullah and Ali Mericar (Indian Muslims), Ibrahim Ma (Chinese Muslim), Mubin Shepard (English Muslim), several of his colleagues from UMNO such as Jaafar Albar and Syed Nasir (of Arab descent), and a few others with religious education. In the informal meeting Tunku proposed the idea to form PERKIM.” — Extract taken from Islamic Herald PERKIM

Muslim Welfare Organization Malaysia (PERKIM) was finally established on 20 March 1977 with Tunku Abdul Rahman as the first president and Mubin as one of the founders. To this day, PERKIM is still active not only in helping Muslims, but also in dakwah.

There is no denying that Mubin was an important contributor to the Malay cultural heritage. His love for the country and its culture was so deep that he chose to remain in Malaysia until he died in 1994 at the ripe old age of 89.

When asked why he was SO invested in this country, he replied by quoting Rudyard Kipling’s poetry:

“Here is my heart, my soul, my mind–the only life I know.

I cannot leave it all behind…”

- 2.4KShares

- Facebook2.3K

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn5

- Email9

- WhatsApp46