Dolphins have been appearing in Penang lately… but where are they coming from?

- 1.3KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter1

- LinkedIn9

- Email20

- WhatsApp31

Imagine walking on a beach, chilling, sipping on a mojito, when you see this:

No, it’s not a sunbathing beachgoer, but a dead dolphin. The pristine beaches of Tanjung Bungah have recently attracted two unusual visitors, in the form of dead dolphins. The first one washed up ashore on the 29th of December, while the second one washed up less than a week later, on January 3. While some of you may be wondering how they got there, a majority might be scratching their heads and wonder instead…

Eh? Penang got dolphins meh?

If asked on where would dolphins live in Malaysia, you might say somewhere in the Pristine™ waters of East Malaysia, or the east coast of the peninsula, but they’re also found in places with not-so-blue water, like Penang and Langkawi. In fact, one of our readers even pointed out that when he was young, you can see dolphins on the ferry ride to the island.

Back in October 2015, a pod of about four dolphins was seen swimming just off the Penang Bridge. It was such a rare sight in Penang that motorcyclists actually stopped on the side of the bridge to watch them. The Sun Daily also reported dolphins being seen a couple of times around Batu Ferringhi last year.

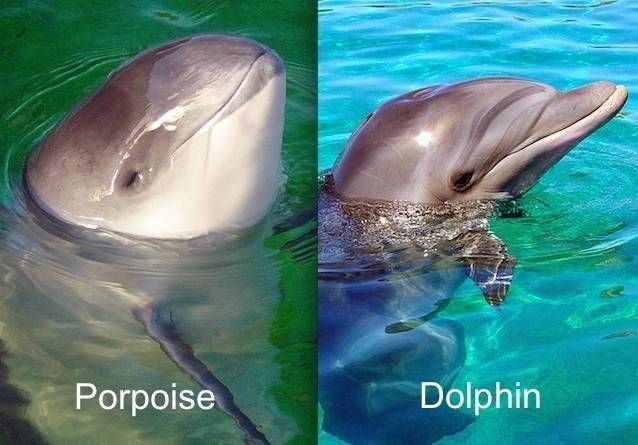

According to MareCet, an NGO that researches aquatic and marine mammals in Malaysia, based on records of live sightings and dead bodies, you can find at least 27 different species of whales, dolphins and porpoises in Malaysia’s waters. These animals belong to a family called the cetaceans, and basically the difference between the three are that dolphins and porpoises are just smaller toothed whales.

Among the 27 species, some are found here throughout the year (resident), while others only pass through Malaysia on their migratory routes (transient). Of course, some of them sesat and found their way into Malaysian waters (vagrants). Common species in Malaysia include:

- Indo-Pacific finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides)

- Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis)

- Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus)

- Gray’s spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris)

- Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni)

- Dugong (Dugong dugon)

Dugongs aren’t cetaceans (they belong to a different family called the sirenians), but hey, they’re mammals who live in the water. While dugongs are commonly found in areas where seagrass grows, like in the Johor Straits, Sabah and Sarawak, cetaceans may be found throughout Malaysia, even in the murky waters of the Malacca strait. This is because cetaceans can adapt to great environmental pressures; they can even be found in the waters of Hong Kong and Japan.

While some parts of the Malaysian sea may seem very polluted, most of the time the murkiness comes from sediment like mud being stirred up by the tides. So, yeah, you can definitely find whales and dolphins in Malaysia. And while the recent dead dolphins in Penang might seem unusual and strange to some, the reality is…

This isn’t the first time cetaceans have washed ashore in Malaysia

In 2016, an almost similar incident happened, also in Penang. A dead dolphin, believed to have choked on plastic, washed up somewhere along the beach off Pulau Jerejak in August. Less than a month later, another dead dolphin landed on the Teluk Bayu beach in Teluk Kumbar, but the cause of death for this particular dolphin is unclear.

Other documented cases of sea mammals found on land in Malaysia mostly involved whales, and these incidents, when cetaceans are trapped in shallow waters near a beach, are called beachings. For example, in 2016, a 20 meter long whale got trapped in shallow waters off the coast of Pontian, Johor. The Bomba, with the help of the local fishermen, managed to rescue it by tying a rope near the end of its tail and dragging it back to the open sea. The Pontian Baru Fire and Rescue Department’s special operations chief later noted that this was the first time they had to perform such a rescue.

Another case of stranded whale happened in Cherating last year, but most other cases happened in Sarawak, around the beaches in Miri.

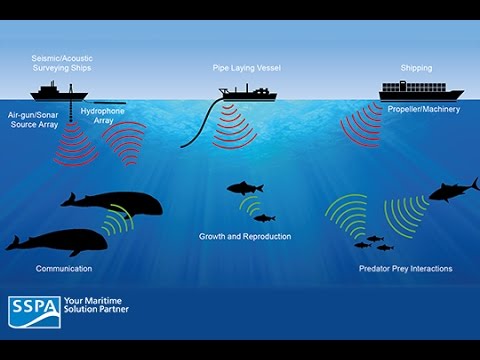

Whales beaching themselves have been documented all over the world, but why are these whales and dolphins swimming so close to shore? Well, no one really knows why, exactly, but numerous theories have been proposed to explain it, from a ship’s sonar confusing them to climate change to the arrival of the monsoon season.

Iqbal Abdollah, the spokesman for Miri’s branch of the MNS, subscribed to the third theory, believing that the monsoon season may mess up a cetacean’s navigational abilities.

“It’s a normal thing to see dolphins beaching themselves and dying on Sarawak beaches. Due to the current monsoon, the porpoise might have lost its way, causing it to head towards a bay. The chances of a beached porpoise living is very slim unless it’s found by people and released back to the ocean as soon as possible,” – Iqbal Abdollah, on last year’s stranded dolphin case in Miri, translated from Utusan Borneo Online.

While cetaceans like whales and dolphins don’t need water to breathe (they breathe through blowholes and have lungs), they may still die out of water. Their bodies are not built to support their weight on land, so without the buoyant force from the water holding up their mass, their organs will be crushed by their own weight.

Also, cetaceans are warm-blooded, and to maintain that heat in the water they often have thick layers of fat. On land, without water to cool them off they may overheat and die. Being stranded in certain positions may also kill stranded whales, as their blowholes might be covered with water, ironically making them drown.

So could the dolphins in the recent Penang case have been saved if people have noticed them earlier? Apparently, we’ll never know, because…

People have complained that the dolphin’s bodies were not handled well enough

Sonya Shah, the woman who lived near the beach and discovered the dolphins, recounted how she and her mother struggled to get help upon discovering the bodies. They called several different bodies, including fisheries, marine rescue teams and wildlife sanctuaries, but each of them passed the job to another body, saying that it is not their job. At one point, one of them even advised her to call the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA).

“Evidently, these deaths must have been unnatural and I am no marine biologist but I know that this could have been avoided. Whether they had been poisoned, gotten lost, suffocated, or caught a disease. We could have helped and it didn’t need to result in death. They are just as worthy of living as we are.” – Sonya Shah, in an interview with FMT.

Andrew Ng, an activist, shared Sonya’s concern. According to him, although the Fisheries Department did come to handle the dead dolphin, they only measured the body and buried it on the beach without determining the cause of death or taking any samples from the body to do that. Upon calling the Langkawi Dolphin Research Center, Andrew discovered that the dolphin is actually an Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin, a dolphin species that turns fully pink when ripe. They are also a near threatened species.

A representative from the Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM) reported the same thing, saying that while the earlier death was reported to the Fisheries Department, there had been no follow-up action.

“They just buried it instead of conducting an autopsy. We would not know the cause of death unless the department or the Fisheries Research Institute of Malaysia carries out a post-mortem,” – SAM representative, for NST.

Dr Leela Rajamani, a senior lecturer from USM’s Center for Marine and Coastal Studies, agreed that a post-mortem is needed to identify the cause of the dolphin’s death. However, she admitted that the center do not have a proper lab for it yet, as they are still looking for funding to build one.

So the actual cause of the dolphins’ death will remain a mystery, but…

Perhaps the dolphins’ deaths could have been prevented

While in most cases we’re not sure why the dolphins washed up dead, human activity may be to blame. In one of the cases in Penang the reason for death was choking on plastic. Fishermen in Sarawak suspects fish bombing to be the culprit for last year’s case of dead dolphins. In 2015, a beaked whale died several hours after it was beached in Bintulu, and the Bomba suggests that based on the whale’s shape, it hadn’t eaten for a few days.

According to MareCet, while there is a lack of research and awareness of them, marine mammals in Malaysia are threatened by a number of human activities. Marine mammals are sometimes entangled in fishing gear, and overfishing and pollution in Malaysian waters are steadily reducing their food. Their habitats are also threatened by large-scale coastal development projects, including reclamation activities, and these activities, along with ships, cause underwater noise pollution that may interfere with their navigation.

However, perhaps the biggest threat to the cetaceans would be plastic pollution, as evidenced by Greenpeace Philippines‘ efforts to highlight the problem by building a replica of a beached whale with plastic trash spilling out of it. According to Dr Aileen Tan, a marine biologist from USM, turtles often choke on plastic trash, thinking those were jellyfish. Based on the dolphin who choked on plastic and died in Penang, she had stated that dolphins can also make the same mistake.

“It’s time for people to realize that throwing away rubbish haphazardly can cause the deaths of sea creatures. We will be starting a major clean-up campaign at polluted beaches in the state soon. I urge other NGOs to join us,” – S.M. Mohamed Idris, SAM president, for The Star.

MareCet had stated that the simplest way that common, everyday people can help these marine mammals is by never throwing rubbish into the sea, as non-biodegradable items such as plastic bags and plastic bottles have a high chance of being swallowed by a marine mammal, and this often causes their death as the rubbish clogs up the mammal’s digestive tract.

But what if you were to chance upon a stranded whale or dolphin? Well, as evident in the previous cases of stranded cetaceans, you can try calling the Bomba for help in rescuing the stranded creature, or you can report the incident to MareCet through this link. For Sarawak, you may lodge a report to the Sarawak Forest Corporation through these numbers:

- Kuching – 082-610088

- Sibu – 084-337444

- Bintulu – 086-313726

- Miri – 085-436637

- 1.3KShares

- Facebook1.2K

- Twitter1

- LinkedIn9

- Email20

- WhatsApp31