Who has more power in their own nation: the Agong or the Queen of England?

- 417Shares

- Facebook374

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn7

- Email8

- WhatsApp20

Being part of the Commonwealth, it’s only natural that we share many similarities with our former colonial masters, the British. And this extends to our monarchy, which shares many elements with the UK’s own constitutional monarchy.

But despite the two heads of state having similar roles and duties in their respective countries, there are some cultural and constitutional differences that set the two apart. Which got us asking: what are those differences, and how do those differences affect the dynamics of each monarch’s rule within their domain?

Let’s look at various elements of each country and compare the two monarchs side-by-side…

1) Legal immunity

When it comes to civil and criminal matters, there is one crucial difference that sets the two apart: unlike the Agong, the Queen is immune against prosecution.

When Malaya’s Constitution was drafted in 1957, the Malay Rulers (the Sultans and the Agong) possessed a similar level of legal immunity. As Article 181 (2) of the Federal Constitution then read:

“No proceedings whatsoever shall be brought in any court against the Ruler of a State in his personal capacity.” – Article 181 (2) of the Federal Constitution, 1957

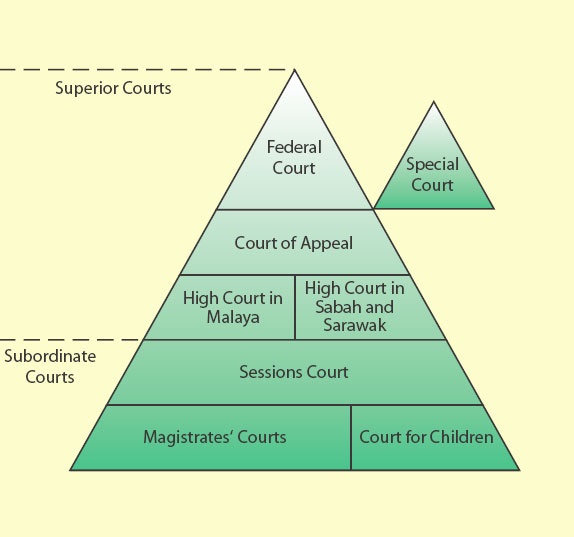

However, following the Gomez incident, the Constitution was amended in 1993. A Special Court was created to hear, well, special civil or criminal matters relating to the Malay Rulers, and the line ‘… except in the Special Court’ was added to the article above. So theoretically, yes, a Malay Ruler can be tried in the Special Court, but even then, only with the consent of the Attorney-General.

As of now, Faridah Begum bte Abdullah v Ahmad Shah (2007) remains the only case ever heard by the Special Court; a libel case that was thrown out as it was ruled that a non-Malaysian could not file suit against the Malay Rulers.

On the other hand, no such mechanism exists for the Queen of England. Period. To put it simply, the Queen is not above the law; she is the law.

Although the Crown Proceedings Act 1947 allows one to sue the Crown (the institution), the Queen herself (the individual):

“… cannot commit a legal wrong and is immune from civil suit or criminal prosecution.” – Rex Non-Potest Peccare: Doctrine Of Sovereign Immunity

Like, she could theoretically walk into any UK store, loot the place, stab someone with a pen, and walk out without being arrested. It’s probably for the best, then, that the Royal Family’s stance on the matter is:

“Although civil and criminal proceedings cannot be taken against the Sovereign as a person under UK law, The Queen is careful to ensure that all her activities in her personal capacity are carried out in strict accordance with the law.” – The British Royal Family

Oh, just as a bonus little fact: the Queen once fired the entire Australian government back in 1975. She’s just that powerful.

2) Military

When it comes to the military, both the Agong and the Queen have nearly identical powers; both are the Commanders-in-Chief of their respective militaries, both have the power to declare war, and both monarch’s decisions to go to war are subject to Parliamentary approval.

Given that the two monarchs share the same constitutional monarchy system, there really aren’t many differences between the roles of the two in military matters; both wield just about equal influence over their armies (which is a lot). With that being said, neither can decide on a whim to attack their neighbors, as, like we mentioned earlier, both are governed under constitutional constraints. The main difference between them here would probably be in the strength of the respective armies (spoiler: the UK’s is a LOT bigger).

Oh, and the fact that the UK has nuclear weapons. Good thing they’re on our side.

3) Succession

This is probably the biggest fundamental difference between the two monarchs: the way they ascend to the throne.

Now, we won’t go too in-depth into how Queen Elizabeth came to power; there’s already a whole Netflix series about that. But TL;DR, in the UK, the monarchy is hereditary, meaning that the throne is passed down through the bloodline.

Granted, there was a whole mess of conflict and bloodshed over these bloodlines (which also incidentally inspired an entirely separate hit tv series), but generally for the UK, the process is the same: father/mother to son/daughter, and so on and so forth.

However, things get interesting when it comes to Malaysia; it’s a rotational system that cycles between the states’ Malay Rulers every 5 years.

We won’t go into too much detail for that either, since we’ve already spoken at length on that process here. But this rotational process means one thing: no one Ruler can hold power for too long. Which, is kind of the point really.

Compare that to the British monarchs, who essentially serve for life (or, in rare circumstances, until they abdicate). And herein lies the problem: unless the monarch dies, there is virtually no way of removing them if they turn out to be bad apples. Well, actually, there is a way, but the Queen herself needs to sign off on it, so, yeah, not really.

Although largely ceremonial nowadays, the monarchs still serve as a check-and-balance

While the Agong does still have a considerable amount of power despite the constitutional nerfs of 1993, there’s no doubt His Majesty has played a vital role as a check-and-balance within our governmental system; arguably even more so than Queen Elizabeth II has done in the UK in recent times.

This was plainly seen when our current Agong stepped in to peacefully resolve the situation of the vacant PM office (twice). Considering our immediate neighbors don’t have as much luck with transitions of government, it’s probably for the best that we have such a mechanism in place.

Because unlike in absolute monarchies, the role of our constitutional monarchy ensures that no one branch of government can become too powerful at any one time. And that’s definitely a good thing, because no matter how you feel about our country’s politics, we really could be doing much worse.

- 417Shares

- Facebook374

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn7

- Email8

- WhatsApp20