The gomen built houses and roads in this Perak kampung, but forgot one important thing

- 2.8KShares

- Facebook2.6K

- Twitter29

- LinkedIn4

- Email39

- WhatsApp132

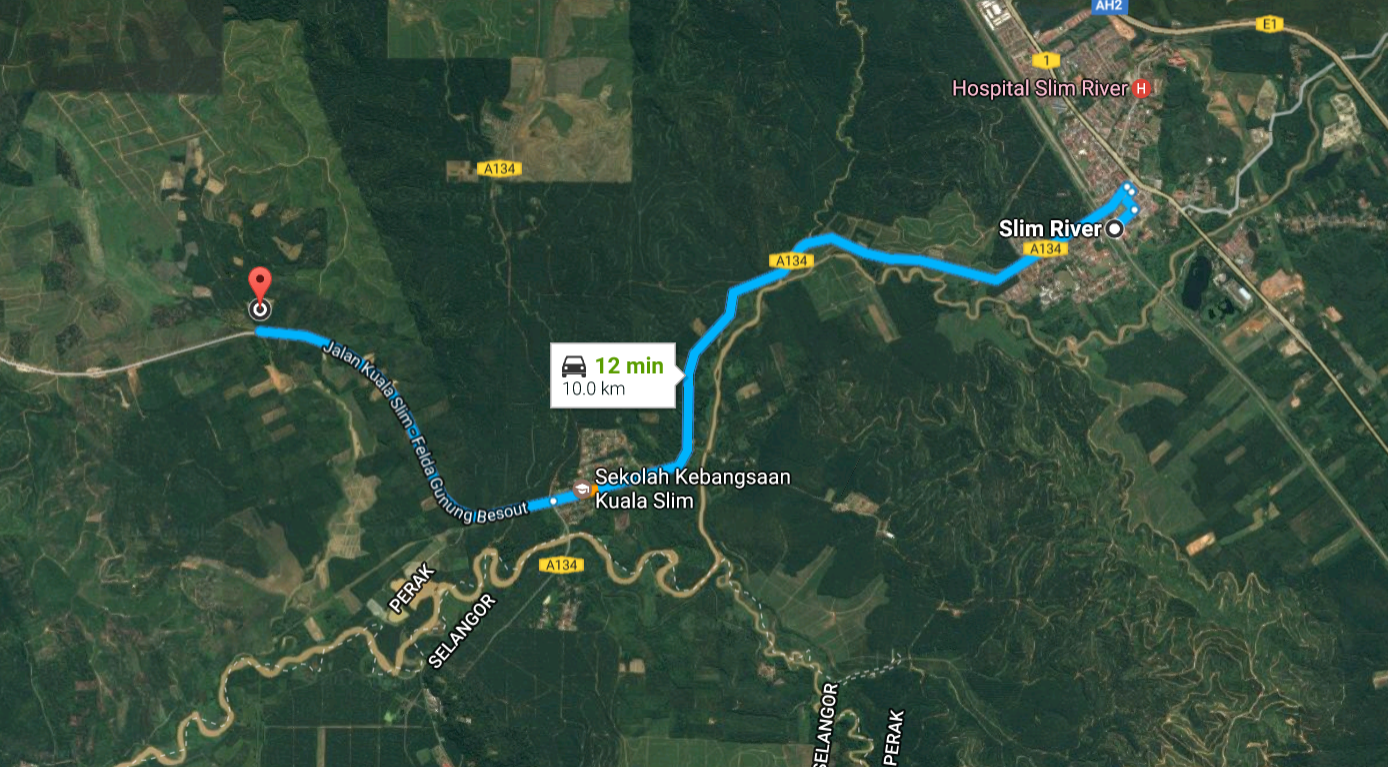

Sometime during the last week, Cilisos participated in a Liter of Light campaign to bring light to a village 30 kilometers west of Tanjung Malim, in Perak. It was an Orang Asli village named Kampung Teras, home to 60 Orang Asli families situated in Slim River, Perak, and it’s not connected to the National Electricity Grid, which means it doesn’t have electricity lah.

And we were a little confused at first.

We were informed that we will be installing solar lights to light up a village not connected to the electricity grid, so we assumed that it will be deep inside a jungle. But a few minutes after taking the Slim River exit on the PLUS highway and trundling down a reasonably well-maintained road, passing some towns on the way, we were quite surprised when our coordinator declared “Welcome to Kampung Teras, guys!”

The village itself was literally a few steps of the Kuala Slim – Felda Gunung Besout road, with a smaller albeit tarred road leading into it. While some houses are still build with bamboo floor and walls with palm roofs, most of the houses were of brick and had television aerials and satellite dishes attached to them. Some of the villagers are even carrying smartphones around. We’re not sure why they don’t have streetlights already, but…

Although so close to a city, this village is not connected to the grid!

It turns out that even with its proximity to the nearest town (3.5 kilometers, or a 5-minute drive), Kampung Teras is off the national power grid. If these people wanted electricity to power up their TVs or charge their phones, they have to resort to a diesel generator. As we later learned, a generator may power up to four houses, and are only turned on a few hours at a time.

A few hours of electricity or light can set them back RM300 to RM500 per month, in terms of diesel for the generators, candles and gasoline for the lanterns. This is a lot of money considering what they are earning as rubber tappers and contract workers, and the unstable income as hunter-gatherers. While a few may be able to afford this cost, most do not. In fact, during our stay in the village houses are mostly dark at dusk, with a few having a single candle burning in their kitchens and one house illuminated with electricity.

As for running water, the village has a solar water pump (which didn’t work at the time) that treats water, that implies they are not connected to the water lines as well. Which brings us to a disturbing question: Why is this village, so close to the main road, and not at all isolated, have neither electricity nor running water? It’s not even the end of the road, too, for if you continue down the main road you’ll eventually reach the Gunung Besout FELDA settlements, which had these utilities.

How hard could it be to tarik the electricity into the village a bit?

It is a hard question to answer. There are two ways to go about this. One of them is grid extension, extending the reach of electricity over an existing power grid. The head of Malaysia’s rural electrification program in this report puts a cost estimate of about $80 million for 130 kilometers. Adjusting for today’s currency, that puts the cost of extending the grid to about RM2.74 million per kilometer. However, that price may include more than just power lines, and extending towards uncharted territory. It probably shouldn’t cost that much when the grid is really close by.

Another way to do this is by powering up isolated communities using either

- a microhydro system, which is like a miniature hydroelectric dam with a miniature output, or

- a solar hybrid system, which is basically a small-scale plant that turns sunlight into electricity.

Both of these systems can work well in Sarawak, where villages are spread out over a large area and connecting each one to a grid would be very costly. However, in the case of Kampung Teras and (spoiler alert!) other villages in similar situations, it won’t do to build a tiny hydroelectric dam for a village surrounded by towns.

There’s also the problem of land allocation for cables and power stations and other assorted electric-producing and transmitting hoo haas, so the simple answer is, while it may be hard, it’s not too hard as to be impossible. With a little bit of funding and effort, it can be done for Kampung Teras and other villages sharing a similar fate.

Wait… so how many other villages are like this?

A few too many. Kampung Teras isn’t the only kampung suffering. According to this study by Chung in 2010, it is found that in Selangor alone, one of the most industrialized states in Malaysia, out of 80 Orang Asli villages, at least ten had yet to be connected to the power grid. If that doesn’t sound like a big deal, among the six villages in his study, four of them had no electricity despite being in a 30-kilometer-radius from the Kuala Lumpur city center. Even though they did request for electricity and appealed repeatedly, the villagers are still left wanting.

And then there’s Kampung Kemensah, which is technically behind Zoo Negara but haven’t got electricity since 1963. The response of the MP is to “install generators and provide subsidies for gas to run the generators before the end of the year”. There’s also the more recent case (2016) of the Orang Asli living at Bukit Tunggul, at the edge of Putrajaya who never had electricity since 1957. While the Dengkil assemblyman had stated that they can’t provide electricity due to “uncooperative landowners“, another statement by JAKOA had suggested that the landowner in question is a golf club developer who had only owned the land since 1993.

Energy poverty is a serious problem for these people, as it is a handicap in today’s society. While some may say that lacking electricity or other basic amenities like water is a sign of poverty, this study suggests that it may be the cause of poverty as well. Houses may not connected to an electricity supply because they cannot afford the bill, but without it it’s harder to do things to improve your life, like studying or opening a small shop. And although nowadays fires caused by electricity are common, candles and lanterns are even bigger fire hazards, especially in a house made of bamboo and palm fronds. There is also the fear of encountering snakes or other dangerous creatures when going out or even sleeping at night, with no lights to scare them off.

Thank God for generous Malaysians and old water bottles!

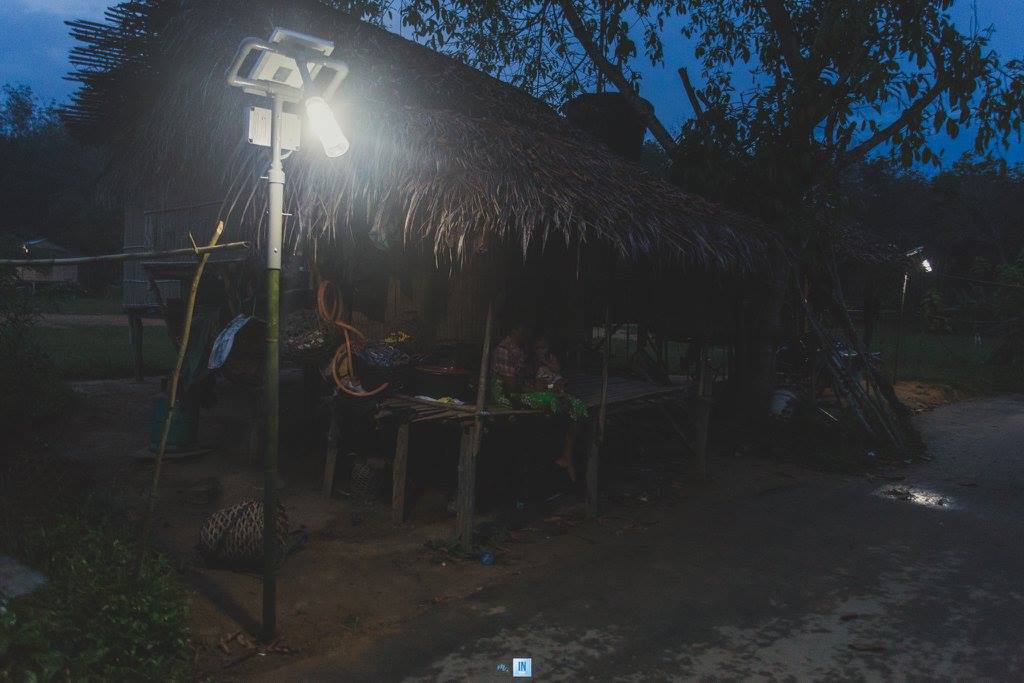

There is a movement in Malaysia that aims to end energy poverty in rural communities by 2020. It’s called the Liter of Light program, where volunteers from all walks of life come together and build solar-powered lights to install in rural villages with no electricity. Although it started in Philippines, now it’s a global thing, where rural communities in India, Pakistan, France and Malaysia, to name a few, benefits from it.

In Malaysia, Liter of Light is brought about by the Incitement, a global social business founded in Malaysia aiming to ‘incite’ people to take action and solve real-world problems. Since they started the Liter of Light program in 2015, they have brought light to 21 villages at the time of this article, with help from sponsors and donations. If you want to support this cause, you can consider applying to be a volunteer, where you will spend two days of your weekend building solar lights and installing them in a village that needs them. Or, if you are a company or a brand, you might consider sponsoring to the cause as part of your company’s CSR or as an investment – you can read the full details here.

Another way you can help is by raising awareness of the issue. The problem with Orang Asli issues, as has been seen many times before, is that their plight very rarely makes it into mainstream media. As can be seen in the recent Bukit Tunggul issue, the public’s opinion helped to bring the issue into focus for the higher-ups and the policymakers. It may not seem that important to us because it’s so readily available, but for some people, a little light goes a long way.

- 2.8KShares

- Facebook2.6K

- Twitter29

- LinkedIn4

- Email39

- WhatsApp132