Why is Selangor still suffering from water supply disruptions, even after 10 years?

- 1.6KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn19

- Email20

- WhatsApp120

[Note: This article was originally published in Mar 2018. Some parts have since been edited to reflect current events.]

If you ever had to choose between no electricity or no water for a month, which would you choose?

Sure, without electricity you can’t charge your phone or turn on the A/C on those hot, muggy nights, but at least you’ll be able to shower and wash your sai and drink. But the effect of water supply disruptions goes beyond sticky armpits and dirty toilets. Long periods of water disruption may affect the economy, cause epidemics, and generally be a great pain in the tushy. Also, with new Covid-19 clusters popping up everywhere including Selangor, having no water can be dangerous as well.

But if you live in Selangor, you probably know that already, because having no water is like second nature for us now.

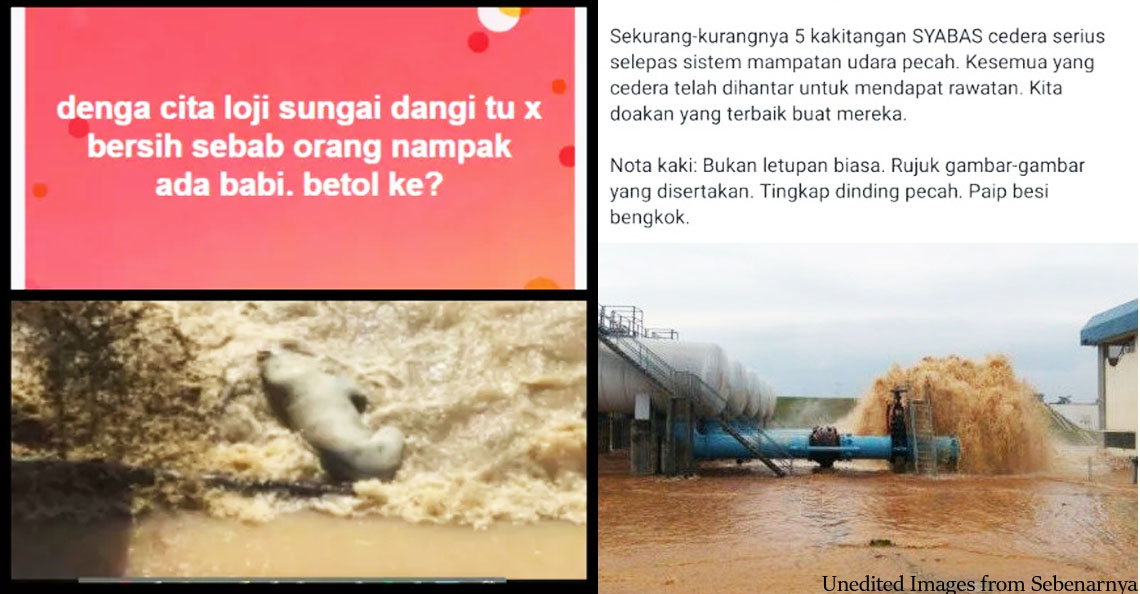

Back in 2018 when we first wrote this article, half a million people in Selangor had to go without water for seven days. Two years later, in October 2020, we’re still scared to poop before checking Air Selangor’s page to see whether there had been a recent water cut or not, since it’s been happening more and more lately. The most recent one on Oct 19th (yes, we have to use a date cause there’ll probably be another one soon) is caused by someone possibly tainting the water supply… again.

With that in mind, you might not be surprised to know that Selangor recorded the highest issues regarding water supply in Malaysia in recent years, even after excluding the cases from KL and Putrajaya. According to Malaysia’s Water Association‘s report, in 2016, 49.5% of all water supply issues in Malaysia was reported in Selangor, and in 2017 the number rose to 62.4%. In fact, surprise water disruptions in Selangor is actually so common that some Selangorians have stopped being surprised by it for a while already.

“The early alerts in social media gave us enough time to start storing water. Still, I am sure Syabas is doing their best,” – Lee Yap Juan, USJ 6 resident, for the Star (2018).

By now you’re probably wondering…

How come Selangor’s water supply system is so bad?

Datuk Seri Dr Zaini Ujang, then the secretary general of the now-reshuffled Energy, Green Technology and Water Ministry (KeTTHA) had said that one of the reasons water disruptions keep happening in Selangor is because the state has very little treated water reserves.

“The water reserve margin in Selangor in 2017 was at zero per cent, which was identified as among the main factors behind the state’s water problems. In the event of a burst pipe, damaged water treatment plant or sudden increase in water demand, such as during festive seasons, there is a high possibility that certain areas in Selangor would experience water disruptions,” – Datuk Seri Dr Zaini Ujang, for the New Straits Times.

Put simply, there’s a limit to how much raw water a plant can treat each day. Excess water is stored in a large tank somewhere to be used during emergencies, such as droughts or burst pipes. In Selangor’s case, there’s almost no excess water: most of the water processed is used up, with no left over. Dr Zaini had said that this is contrary to best practice, which recommends at least a 10% reserve. By comparison, Penang had been quoted to have more than 30% in reserves.

Another reason behind the recurring water problems is that the development of Selangor is happening at a rapid rate, yet the water supply and distribution system had been barely upgraded for several years now (we’ll get to that later). Burst pipes happen frequently as the pipes were from a time when Selangor’s water demand wasn’t as high as it is now, and they’re not designed to handle the increased pressure. In 2017, Selangor used up more water (234 liters per capita) compared to the national average (209 liters per capita, the highest in South East Asia, btw). While Selangor’s usage per capita is not much different than 1998 (228 liters per capita), the population had grown a lot since then, so you can just imagine the strain on the pipes.

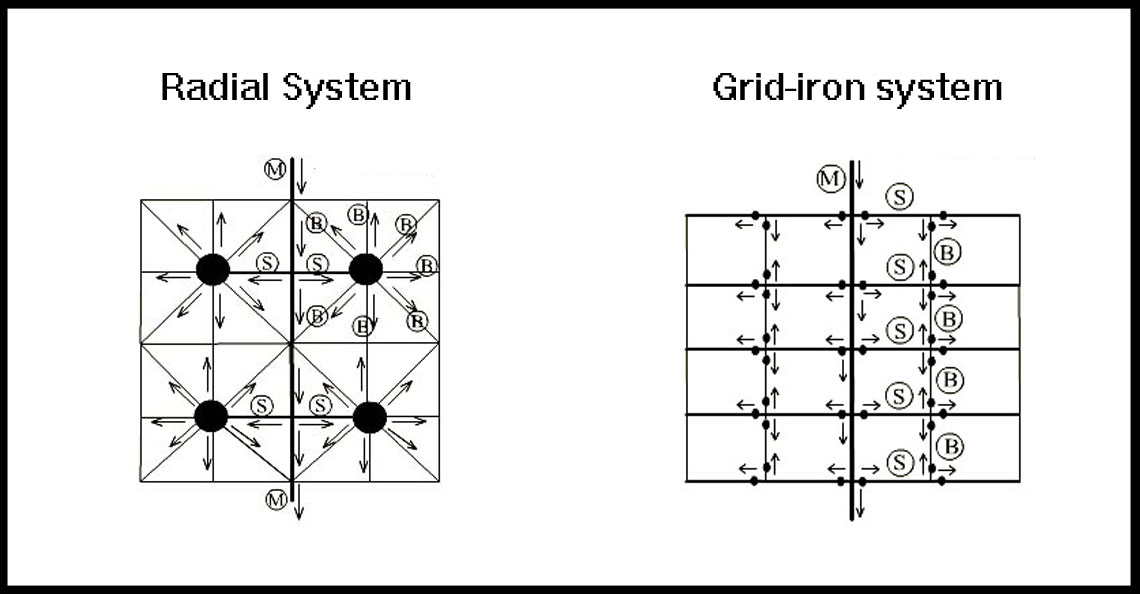

Dr Zaini also noted a problem with the layout of the pipes themselves. According to him, the water distribution system in Selangor follows a radial pattern, and while there are advantages to this layout, one burst pipe will cut off the water supply for a whole area at least. While he proposed a grid system as an alternative that will increase water supply connectivity, it won’t be much use if there’s no spare water to channel in the first place.

So now we know that the current water distribution system in Selangor is hardly adequate to support its population and ever increasing development, and it needs to be overhauled to a better version to keep up. However, it’s easier said than done at the moment, because…

Until very recently, the government only has power over PARTS of Selangor’s water supply system

The question of who’s responsible might sound like an obvious one: the government lah, duh. However, it’s not as simple as one, two, duh. In 2005, the Malaysian Parliament amended the Federal Constitution, and since then water supply became the responsibility of both the federal government and the governments of each state (except for Sabah and Sarawak).

Notice how the 2018 quote from the beginning of the article mentioned ‘Syabas’? Before the Federal Constitution amendment, supplying water was the responsibility of the state government alone, and some states gave licenses to private companies to do all the water-supplying work for them. For Selangor, there were four:

- Syarikat Bekalan Air Selangor Sdn Bhd (Syabas)

- Puncak Niaga (M) Sdn Bhd (Puncak Niaga)

- Konsortium Abbas Sdn Bhd (Abbas)

- Syarikat Pengeluar Air Selangor Sdn Bhd (Splash)

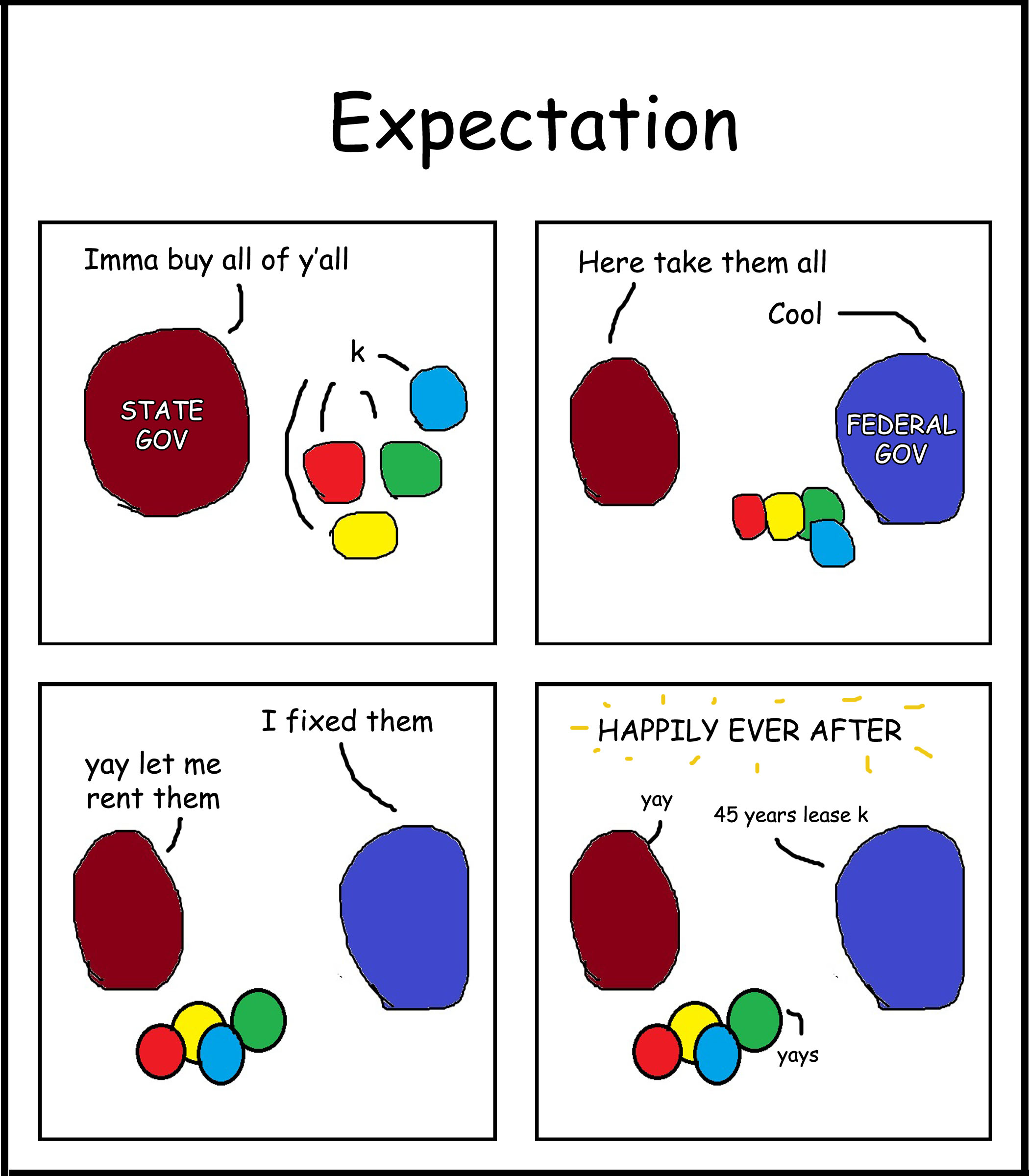

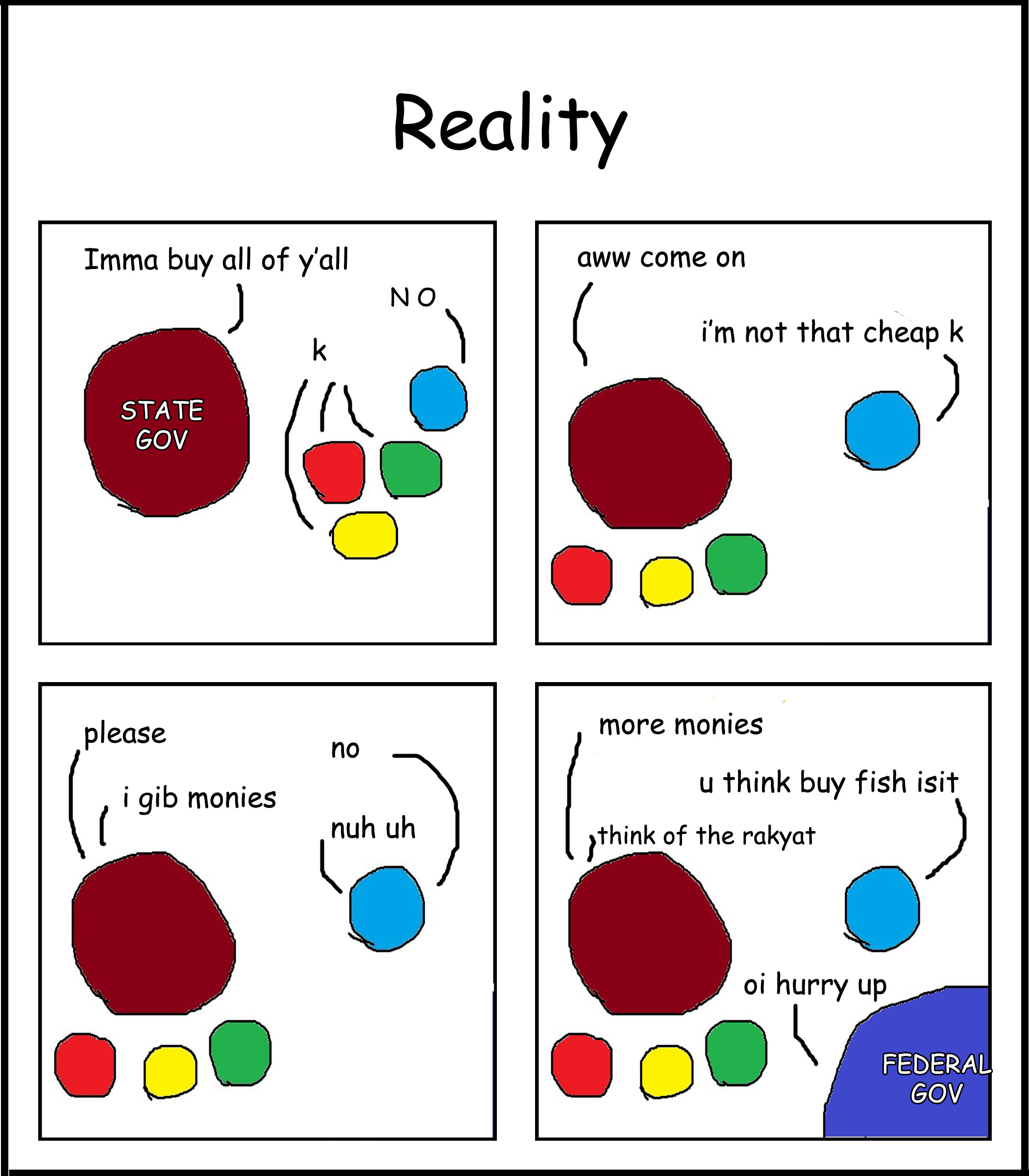

To change the administration of water services in Selangor, the state government planned to acquire these four companies under a new entity called the Pengurusan Air Selangor Sdn Bhd (Air Selangor). Once Air Selangor acquires them, the ownership will be transferred to a federal government agency called the Pengurusan Aset Air Bhd (PAAB). The PAAB will then lease these companies back to Selangor. That sounds a bit much to handle, so here’s a comic illustrating the relationship between the State Government, the Federal Government, Syabas, Puncak Niaga, Abbas and Splash.

With this arrangement, the federal government will be able to use its money and discretion to upgrade and maintain Selangor’s water systems, and Selangor pays a sort of rent to the federal government in return.

In 2015, the PAAB managed to acquire Syabas, Abbas and Puncak Niaga, but Splash refused the initial offer. Gamuda Bhd, the company that holds a 40% stake in Splash, refused the state government’s offer of RM250.6 million, saying that accepting the offer will incur a divestment loss of RM920 million. Despite concerns, the previous Menteri Besar of Selangor, Tan Sri Khalid Ibrahim finalized the deal without Splash just before he retired.

“As the project owner, Splash accepts the re-nationalising of water concessions… We want a closure that is fair, so that all stakeholders can move on. Our main concern is to have Splash accorded fair valuation according to its one-time book value. As at Dec 2016, Splash’s book value is RM3 billion. We’re not even pressing for inclusion of the remaining 14 years of Splash’s concession. In my opinion, this is already a huge discount,” – Tan Sri Wan Azmi Wan Hamzah, Splash chairman, to the New Straits Times.

The Splash website stated that the assets it owns have the capacity to supply water to 45% of Selangor and KL. Yikes. So negotiations have been going on between the state government and Splash ever since then, but as they can’t both agree on a price, the deal keeps getting postponed.

So why not just give Splash whatever price they asked for? According to Hisham Jalil, president of Sukarelawan Malaysia, a higher price as wanted by the concessionaire will result in a higher lease to the state government, causing water tariffs to go higher. And since the deal is yet to be finalized, only minimal upgrading had been done on the water systems owned by Splash so as not to interfere with the valuations of the assets.

Yes. So the reason you still have to keep a dump bucket handy for the past few years is probably because of this tug-of-war.

There are two ways this could end

Datuk Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali, Selangor’s former Menteri Besar, had stated back then that the problems with water supply in Selangor had nothing to do with the state’s water reservoirs, but was rather due to Splash’s failure to maintain their assets. Basically saying that the state’s hands are tied in this matter, he stressed that it’s not fair to politicize the issue and blame the state government, as they don’t have the power to maintain Splash’s assets.

“If it’s not our house, if it’s not our asset, how can we take action and perform maintenance? …we can’t butt in as it’s Splash’s facility, so we’re asking for SPAN’s (Suruhanjaya Pengurusan Air Nasional) permission to conduct an investigation,” – Azmin Ali, translated from Astro Awani.

The former Menteri Besar, Khalid Ibrahim, had on the other hand blamed the Selangor State Government as well as Azmin Ali for not yet acquiring Splash after so many years, saying that Azmin is not being serious about the issue and cares more about paying Splash RM2.7 billion than caring about the state’s water problems, and the wishy-washiness is a form of negligee negligence.

“It is negligence on the part of the state government. This negligence has given room to the shareholders of SPLASH to gain more profit until they have become this brave. A mentri besar should fight for the people, but one’s movements might be restricted because you are too full to the point of vomiting,” – Tan Sri Khalid Ibrahim, as reported by the Star.

The main issue in tackling Selangor’s water woes is probably for the state government to take over the equity in Splash, and only then can the facilities be upgraded and maintained sufficiently. With the deal kept getting postponed, the federal government had threatened to invoke the Water Services Industry Act 2006, specifically Section 114, which grants power to the minister to instruct the National Water Services Commission to seize control and operations of a water concession licensee based on national interest. In other words, if the minister can justify that acquiring Splash will benefit the people, control of Splash’s facilities will be forcibly taken, with payment or not, by July this year.

Perhaps fortunately, things progressed with minimal bloodshed since then. In Feb 2020, however, all of Selangor’s water supply facilities finally came under one entity (Air Selangor), after a year of negotiations. With that, hopefully Air Selangor can begin the upgrades to Selangor’s water system to better serve its rapidly growing population. So far, we have not seen a mention of when that will happen, but until that happens, we can try one other thing on our end: addressing the water demand.

While water consumption per individual hasn’t gone up, the number of individuals has. With the lack of water reserves in Selangor, maybe we can stand to use a little less water each. Back then, the state policy didn’t seem to encourage this, with Selangor having offered 20 cubic metres of FREE water to Selangor citizens.

“Water tariffs in the country should be raised to realistic levels to deter the public from wasting water even though Malaysia is among those countries receiving the highest rainfall in the world. The problem is Malaysians see water as something cheap compared to other essential utilities as the water bill for the average household is only 10% of the electricity bill because the tariff is the lowest in the region.” – Dr Haliza Abdul Rahman

However, earlier this year, Selangor had introduced the Skim Air Darul Ehsan policy, which limited the number of people getting 20 cubic meters of free water to only 184,020 households. It would seem that with no more reason to not upgrade the water systems as well as less frivolous water policies, the water situation in Selangor might improve someday in the near future. But more can realistically be done to address our water woes, in terms of better enforcement against pollution, for example.

Will these be addressed in the near future as well? Perhaps, if there is a political will to address them. Until then, we’d keep our water buckets close.

- 1.6KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter8

- LinkedIn19

- Email20

- WhatsApp120