The history of the Malay language, from Pallava to Jawi to modern Malay, simplified

- 2.3KShares

- Facebook1.9K

- Twitter32

- LinkedIn27

- Email48

- WhatsApp287

If you’d like more stories like this, feel free to join our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group ?

So recently, there’s a huge uproar about teaching SJK students khat, or calligraphy in Jawi script. We won’t go into too much detail about that, since a lot have been written about it (MalaysiaKini actually did a pretty comprehensive explainer on that). But here’s a basic version of what happened:

Plans of teaching khat got leaked out, some education groups and people got miffed and protested, people got divided and poured out their strong opinions against each other, politicians scrabbled around trying to put out the fires, and recently, the issue got settled with a sort of “if you want to learn, can, if don’t want also can”.

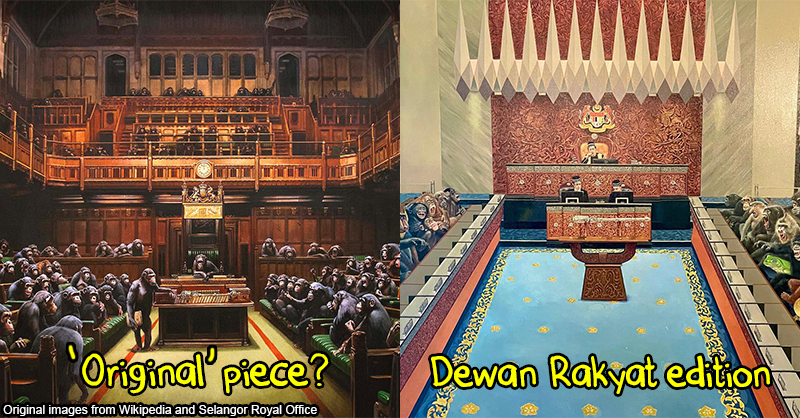

Right. So pretty much another day in democratic Malaysia Baru. Being the scholars that we are, we decided to look past the burning buildings and see what’s the deal with Jawi, how it came to be, and how come we’re still keeping it around when we have these convenient Latin letters (commonly known as Rumi). After all, we’re pretty sure most of us see instances of it every day…

…but how many of us actually know the history behind it? Well, that’s what we’ll be talking about today, starting with the (perhaps) surprising fact that…

Before Jawi, Bahasa Melayu was written in Rencong and Indian-based scripts

[Update 22 Aug: One of our readers, Araduas Rasis Razali, pointed out to us that Rencong may not have been derived from Indian based-scripts after all, being considered an original Malay invention. This article had been changed to reflect that.]

While many might equate the history of the Malays with the keris, Sultans, mountain princesses, and trade with the Arabs, the history of the Malay language started way before that. The history is a bit fuzzy, as not much interest was given towards the history of the Malay language until roughly the colonial times, and most of what we know today came from surviving relics, like tombstones and stone inscriptions (Batu Bersurats, if it helps).

Like many other languages, Malay went through several evolutions before becoming what it is today. Before the 7th century, the Malay language was termed as Ancient Malay or Proto-Malay (aka Melayu Purba). This was a prehistoric time, and so far no written records have been found of this kind of Malay, leading to the belief that at this point, it’s a purely oral (spoken) language, with no written script.

The people in the Malay archipelago then made contact with Indian traders, and consequently their religion and language. Having received heavy influence from Sanskrit as well as ideas found in Hindu-Buddhism, Ancient Malay evolved into what is known as Old Malay (Melayu Kuno). It seemed to rise to prominence sometime between the 7th and 13th century, during the height of the Srivijayan empire.

According to a source, Sanskrit at that time was seen as an atas kind of language, being the language of scholars. So even though several concepts already have Ancient Malay terms, they were replaced by adapted Sanskrit words. It is believed that some prefixes and suffixes in modern-day Malay gained its roots here, like adding ‘-ku’ at the end of words to denote possession (‘keretaku’ = my car, ‘buahku’ = my fruit, etc), plus other prefixes like ‘ber-‘ and ‘di-‘, although their spellings were different in Old Malay (‘mar-‘ and ‘ni-‘, respectively).

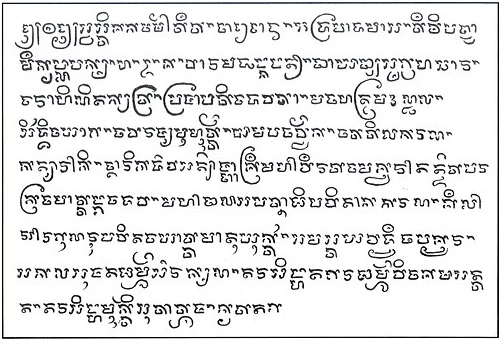

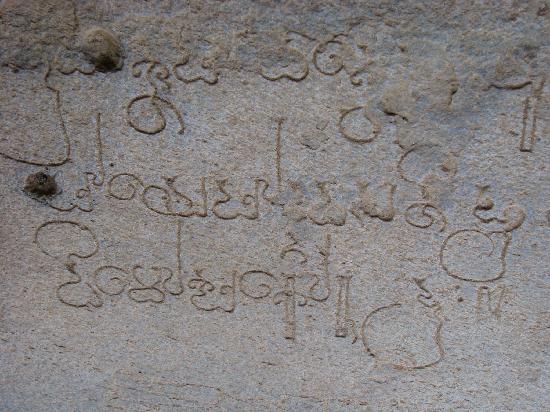

Several inscriptions in Old Malay have been found over the years, and they seem to use scripts adapted from Indian scripts, like Kawi, which looks something like this…

and Pallava.

Another script called Rencong, believed to be an original Malay writing system, was also used at this time.

Old Malay reigned popular up until the early 13th century, when…

Trade with the Islamic world brought Islam, as well as the Jawi script

While we stated rough dates for the previous transitions, they were never sudden changes. The dates were estimates for the timeframes when each version of Malay probably became widely used. Jawi was said to have become popular starting the 13th century with the arrival of Islam, although some might argue that Islam in the region precedes the Jawi script, with tombstones and historical sailing logs that suggest Islamic practice as early as the 8th century.

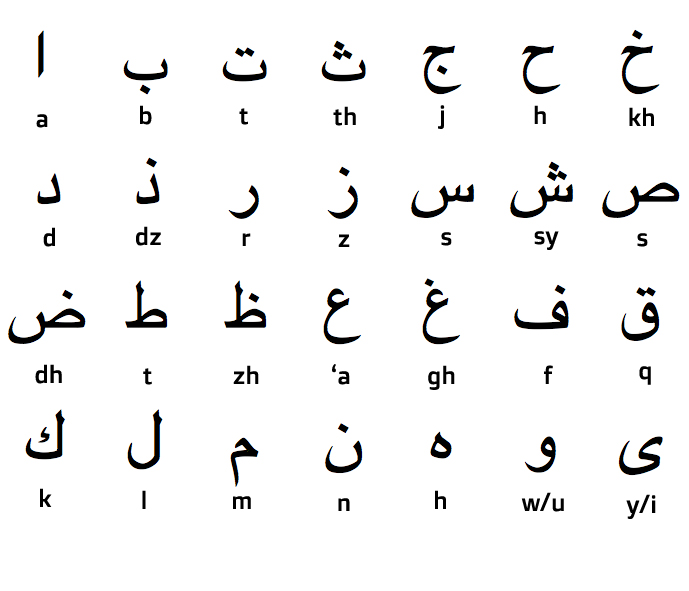

Jawi script is derived from Arabic, but with a difference: it has six additional characters added/adapted to represent sounds in Malay not found in Arabic, i.e. /c/, /ng/, /v/, /g/, /ny/ and /p/. As for why people would switch to a whole different writing system, it has something to do with learning Islam.

[Okay, side note. The Arabic character with the ‘y/i’ sound actually has two dots underneath it, but writer realized too late so too lazy to edit. Without the dots, it’s a not-commonly encountered additional character in Jawi that carries the sound of either ‘a’ or the ‘e’ in ’emak’, usually used for loanwords. Don’t @ us about this please. End of side note.]

In the beginning, there were efforts to learn Islam from its two main sources: the Al-Quran, the main text of Islam, and the Hadith, which is a collection of sayings and behaviors of the Prophet Muhammad. These were mostly in Arabic back then, so to read them you need to know Arabic letters. Plus, in Islam, the correct Arabic pronunciation of certain prayers and phrases is important, something that the existing Sanskrit-based scripts cannot accurately portray.

To solve both problems of inaccurate pronunciation and unfamiliarity with the Arabic script, the Jawi script was introduced. This isn’t really a phenomenon unique to Malaysia, actually. For example, the Chinese language has their own version of ‘Jawi’ commonly caller Xiao’erjing, used by Muslim minority groups in parts of China.

With the introduction of the Jawi script and a generous helping of Arabic and Persian vocabulary, Old Malay morphed into Classical Malay. This form of Malay is different from its previous version in many ways, like having longer, more complicated sentences, the usage of ‘pun’ and ‘lah’, a change in grammar and sentence style influenced by Arab, and the popularity of sentence starters like ‘hatta’, ‘alkisah’, and ‘adapun’. This is the kind of Malay you see in Sultanate historical dramas.

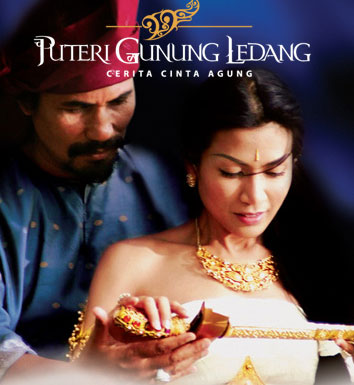

The Malay language and Islam became really popular in the region, and some had credited Jawi as the catalyst for that. At its height, it was used by both the common folk and for official affairs, no longer being limited to just Islamic classrooms. The Sultans of that time were even said to write letters to foreign monarchs in Jawi. With the booming trade, Malay and Jawi became the lingua franca of the region, but Jawi soon fell out of popularity when…

Westerners introduced the Roman script to the archipelago

It’s unclear when people started romanizing Malay, but sources would point to sometime after Malacca fell to the Portuguese. A teaching document suggests that the first angmoh to romanize Malay was a person named Duarte Barbosa in 1516, but it didn’t say much else. He was said to have accompanied Magellan on his circumnavigation of the world, but another friend of Magellan named Antonio Pigafetta was credited with the first ever romanized dictionary of Malay.

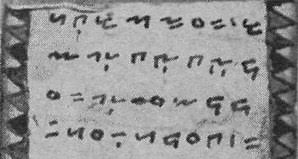

Pigafetta’s dictionary contained about 400 words. However, as can be seen in this sample…

…his spelling seems to be based on the sound of the words in Italian, instead of a transliteration from Jawi. Over the years, as Malaya changed hands, several other dictionaries and spelling systems for Malay in Roman script were published, but the spellings differ quite significantly, by time and region based on who’s colonizing.

Of interest was the case of Malaysia vs Indonesia spelling: after the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1824, Malaya went under the British, while Indonesia went under the Dutch. In the early 1900s, it was said that Malaya standardized its spelling for official use using the Wilkinson spelling system, while Indonesia used the van Ophuijsen spelling system, which spelled Malay words according to Dutch sounds.

The commonly seen difference was that the van Ophuijsen system uses ‘j’ for ‘c’ and ‘y’ sounds: ‘jari’ in Malaya was spelled ‘tjari’ in Indonesia, ‘nyawa’ was spelled ‘njawa’, etc. Oh, and ‘u’ sounds are written as ‘oe’. Like this:

Several improvements to the system happened after that, perhaps notably by a Malay scholar named Za’ba, who among other things identified the six vocal sounds used in Malay and set down several rules in transliterating Jawi words into Rumi, the Roman script.

Sometime in 1967, Malaysia and Indonesia got together and standardized their spelling systems, and since then, the spelling system for Malay words in Malaysia had been maintained by the Dewan Bahasa and Pustaka (DBP).

So with the Rumi script in place and more vocabulary added to the language over the years from various colonizers, Classical Malay turned into the modern Malay we know today. And unlike Kawi, Pallava and Rencong, which can barely be seen today, Jawi is still being used in modern day Malaysia. However…

Although it’s still being used, some fear that Jawi will soon be forgotten

Academically, there might still be value in learning the Jawi script. Jawi did make up a huge part of Malaya’s history, and in the 700 or so years when Jawi was the belle of the ball, thousands of historical documents were written in it. Even (perhaps) the most recognizable historical document we have, the Declaration of Independence, was written in Jawi. However, at least 4,000 of these historical documents are still waiting to be researched and/or transliterated into Rumi.

With the improvements in spelling Malay words in Rumi over the years, Jawi had not been neglected by Malay scholars, with more rules added for spelling with it to remove ambiguity. But although both systems are still being used today, Jawi is considerably less popular. Sometime in the 1960s the National Language Act 1963/67 was implemented, and it effectively established the Rumi system as the official writing system for Malay, although it’s not wrong if people want to use Jawi.

“The script of the national language shall be the Rumi script: provided that this shall not prohibit the use of the Malay script, more commonly known as the Jawi script, of the national language,” – Section 9 of the National Language Act.

Today, Jawi is still being taught in schools, most noticeably in the subject of Pendidikan Islam, where the official textbooks are written almost entirely in Jawi. However, there is a concern that Jawi is becoming less and less popular, particularly among the younger generation. It must be noted, however, that we are unable to find the exact statistics to back this statement. Regardless of that, to fix the perception, some state governments and NGOs have tried using the script more in banners and signboards, and by holding campaigns to rekindle the people’s interest in the script.

Regardless of how people may see Jawi, it can’t be denied that it is a significant part of Malaysia’s history, but whether or not it will still be relevant in Malaysia’s future… that’s not really something we can say for certain.

If you’d like more stories like this, feel free to join our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group ?

- 2.3KShares

- Facebook1.9K

- Twitter32

- LinkedIn27

- Email48

- WhatsApp287