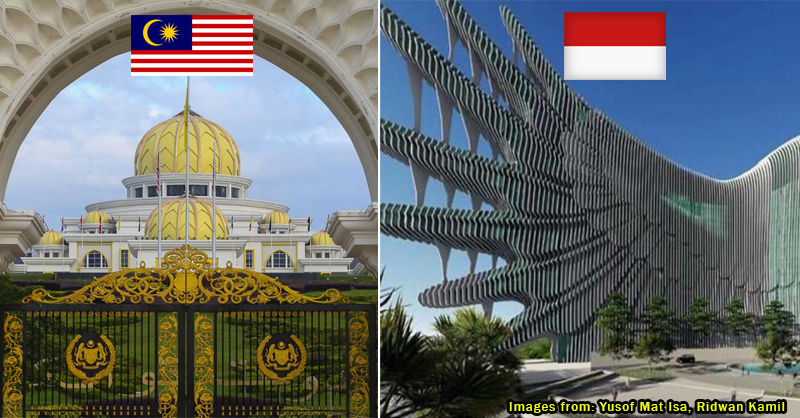

Malaysia vs Indonesia: who has nicer national buildings?

- 428Shares

- Facebook391

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn5

- Email5

- WhatsApp23

With Indonesia having approved the relocation of their capital to Nusantara, Borneo, it’s only natural that they’d commission a sleek, new presidential palace to go with it. And it is sleek indeed:

Although we’ve got the edge over Indonesia in a few other things (like football rankings, for instance), we gotta admit that the winning design for their new presidential palace is pretty impressive, and it does kinda make us a little bit jealous.

Which kinda got us thinking: we’ve got some pretty fancy national buildings too, so how do ours compare to Indonesia’s? We decided to take a closer look at the design of some of these, and we learned some interesting things. Let’s start with our legislative hubs…

1) Parliament

What’s pretty cool about Indonesia’s parliament complex, the MPR/DPR/DPD Building (named so because it houses three different legislative bodies), is its futuristic exterior, modeled after the wings of a Garuda. It also kinda reminds us of the Galactic Senate building from Star Wars. I mean, just look at it; it looks a like a friggin’ spaceship.

Designed by Soejoedi Wirjoatmodjo and commissioned by their first President Sukarno in 1965, its construction faced several hiccups (including the 30 September Movement), but the main building was finally completed in 1968, with other parts of the building completed in stages over the course of the next few decades.

Interestingly, the six buildings in the complex were given Sanskrit names due to Sukarno’s Javanese influence, which proved problematic as even MPs would mispronounce them sometimes (try saying Samania Sasanagraha really fast 5 times) . But in 1998, student protestors took it over, a revolution toppled Suharto’s government, and all the buildings were renamed with more Indonesian-friendly names (such as Nusantara, Nusantara I, Nusantara II, Nusantara III… you get the idea).

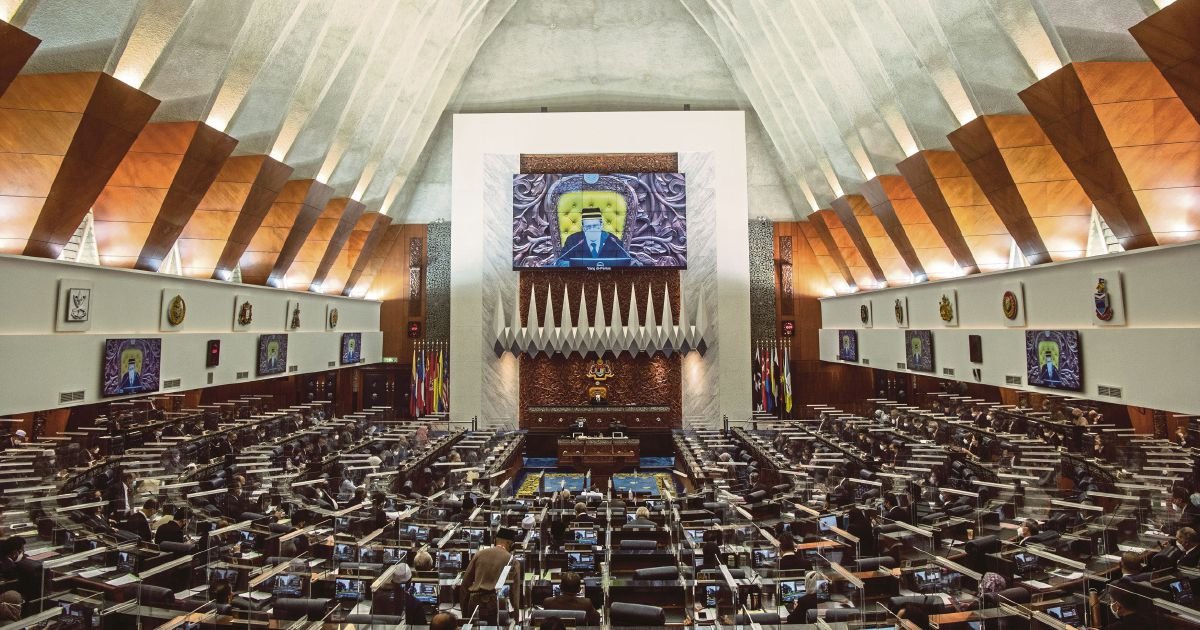

The interior of its House of Representatives is no less impressive: housing 575 members, its design is reminiscent of the WWII-era German Reichstag in Berlin (we only know this because we played Call of Duty: World at War). This could be due to its European (Dutch) colonial influence; in fact, Indonesia’s legislature, the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR), began as something known as a Volksraad (Dutch for ‘People’s Council’.

On the other hand, Malaysia’s Parliament building in KL, appears to have been built with utility in mind, rather than style. At a glance, the immediate obvious difference between Malaysia and Indonesia’s parliament buildings is that ours was built to be tall, while Indonesia’s was built to be wide. And there’s a reason for this: Malaysia’s Parliament’s exterior design fits in with the architectural principle of sustainable building for tropical climates:

“In hot-humid climates, this depth should be limited in order to promote air circulation, and the rooms should be arranged in a row and provided with large openings on the opposite exterior walls.” – Sustainable Building Design for Tropical Climates

(On another note, it’s quite ironic that KL’s KTM railway station was built to withstand snowfall.)

Officiated in 1963, the Parliament building was built using over a million bricks, and makes up for its relatively generic, boxy design with various other facilities, including a fancy multipurpose sports hall, banquet hall, and even a Deer Park. Oh, and fun fact: the building’s foundation stone contains a time capsule containing various trinkets and memorabilia from the time.

Another difference from Indonesia’s would be the layout of the respective houses of representatives: while Indonesia’s has seats all lined up straight facing the Speaker’s seat, Malaysia’s has 222 parliamentary seats arranged in a circular manner with the Speaker’s seat as the central fixture, similar to the US House of Representatives.

Winner: For style, Indonesia; for practicality, Malaysia

2) Palace

Indonesia seems to have a fascination with presidential palaces; they have six. But we’ll only be focusing on the one currently used as the official Presidential Palace, the Merdeka Palace.

What’s cool about our respective palaces is that they show the crucial differences between our forms of government; as a republic, Indonesia’s Dutch-designed Merdeka Palace in Jakarta appears to have done away with the grandiosity of traditional monarchic architecture, favoring a more muted, minimalist look akin to the US White House in Washington (the Americans are also a republic).

Built by the Dutch colonialists in 1879 as the Paleis van de Gouverneur Generaal (“Palace of the Governor-General”), the Merdeka Palace is an upgrade to the original presidential palace, the Istana Negara (built 1796), which lies in the same compound. Both palaces have porticos supported by Corinthian and Doric pillars, typical of Dutch architecture at the time (buildings such as the White House in Washington, D.C. and Atatürk’s Mausoleum in Ankara, Turkey also have this feature).

Of course, if the preliminary designs of the proposed new palace in Nusantara are any indication, the no-grandiosity principle may well be going out the window, because damn, the new one looks kaiju-level massive:

Now, Malaysia’s Istana Negara on Jalan Tuanku Abdul Halim looks more like a King’s residence (which it is). Opened in 2011, it replaced the old Istana Negara located elsewhere in Kuala Lumpur (which now serves as the Royal Museum).

The distinctive golden domes are reflective of the Agong’s status as Head of State, as well as Malaysia’s deep Islamic roots. And, as anyone driving past it on the way to work will have noticed, it’s built on a hill, with an area encompassing 96.52 hectares (although only 28 hectares are used for the actual palace complex, with the rest serves as a garden). The surrounding existing forest was also developed into a public garden on the request of the Agong.

It’s also guarded round-the-clock by soldiers of the Agong’s regiment, the Royal Malay Regiment, who basically just stand still for the duration of their shift ready to sniff out threats, similar to the Queen’s Guard at Buckingham Palace. In fact, there’s even a Changing of the Guard ceremony at the palace which happens at 12 pm every day, as well as a larger version of that ceremony held monthly, so be sure to check those out next time you pay a visit:

Winner: For history, Indonesia; for architecture and tourism, Malaysia. But of course, that could change once Indonesia’s Nusantara palace is completed.

3) National monuments

Now, when we first saw Indonesia’s National Monument (Monas), we thought it was just another nationalistic pole monument, similar to Nelson’s Column in London. But that changed when we found out its origin story.

Thought up by Sukarno himself, the building was designed as a symbol of, um, masculinity and femininity, to use the most polite terms. You’ll know what we mean when you see it:

And if you thought we were making that up, no we weren’t; Friedrich Silaban, its architect, was told by Sukarno (of Javanese descent) to design it with the Hindu concepts of lingga (phallus) and yoni (vulva):

“It’s actually not very local, because it’s derived from Hindu traditions of India, who have long influenced Java. I don’t know exactly why they used it anyway, because it’s actually very Java-centric.” – Setiadi Supandi aka Cung, biographer of Friedrich Silaban (translated from Bahasa Indonesia by Cilisos)

But that’s not the only controversy surrounding it; despite it being built as a symbol of their struggle to win independence, Indonesians were initially against its building, as its announcement was deemed too soon after independence, especially during a time of economic uncertainty.

Now, for Malaysia’s national monument, we’re pretty sure everyone’s familiar with its iconic design. Our Tugu Negara is actually located a stone’s throw away from Parliament, and is a more realistic depiction of an independence struggle; it’s literally a statue of soldiers in combat and raising the Malaysian flag, with one soldier holding a wounded comrade. At their feet are a pile of bodies, symbolizing the poignant truth that our nation was built on the blood of the fallen:

Unveiled in 1966, the Tugu Negara was actually bombed by the communists in 1975, cos, well, no one likes a monument essentially built as a symbol of victory over them. But the Tugu Negara has also received its fair share of opposition from regular Malaysians, since Islam forbids idolatry (hence why you don’t see any images of the Prophet or anyone else at mosques).

Although both monuments hold significance in their respective countries, they’re both clearly very, very different. We guess it’s just a matter of taste, but personally, we’re going with Malaysia’s for this one (though admittedly, Indonesia’s monument’s origin story is hard to beat).

Winner: Malaysia’s for craftmanship and emotive effect; Indonesia’s for origin story

Both countries’ buildings are pretty to look at, but also capture historical and political differences

Although we share a similar language and culture, Malaysia and Indonesia went in very different directions following colonization by the British and the Dutch, respectively. On the one hand, you have us, a constitutional monarchy with deep ties to Islam which exist to this day, and then you have Indonesia, a secular republic who severed their ties to royalty a long time ago.

And these differences are reflected in the way we build our buildings, each designed to accommodate the national ideologies of the current era. At the end of the day, no matter how you feel about the governments of past and present, these buildings are important as they serve as part of our national identity, as well as a reminder of how we came to be.

- 428Shares

- Facebook391

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn5

- Email5

- WhatsApp23