A mysterious disease called ‘serawan’ is killing off 50% of Orang Asli children… OMG are we all in danger?

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter18

- LinkedIn15

- Email26

- WhatsApp55

Imagine having your children dying of a strange, mysterious disease, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

While such a scenario might seem unthinkable in modern-day Malaysia, that was what happened to a community of Jahai Orang Asli living in the Sungai Kejar area, which is near the Royal Belum State Park. In 2015, the R.AGE team covered the story of a mysterious disease called ‘serawan‘ killing off the children of the Jahai community. For those of you who haven’t seen the video yet, here it is:

Kamal Sohaimi Fadzil, an anthropologist from Universiti Malaya that the R.AGE team spoke to, estimated the child mortality rate for the 20 or so families living in the Sungai Kejar area to be 50%.

In case that wasn’t clear enough, only HALF of the children there lives. One of the villagers claimed to have lost five of his children to serawan.

“I know four people who have died this year, all from this same disease. We used to have around 600 people in the villages here, and we were happy. Now there are around 400 of us left.” – Bain, one of the Jahais living in the Sungai Kejar area, as reported by R.AGE.

The rate at which people died in this case was the same as the mortality rate of the infamous Ebola virus, so you know that’s some serious sai right there. The R.AGE team later consulted the JAKOA about this, but surprisingly there were no deaths recorded in the area for the past year. The district officer they spoke to haven’t even heard of a disease called serawan. An interview with the state’s health department yielded similar results: only one adult death in 2014, despite one of the villagers having a death certificate for his daughter’s death to serawan.

So which side was right? A disease that killed off half the children in a somewhat isolated community, or state officials who insisted that there had been no recent infant deaths? In this particular case, statistics (not JAKOA’s) lean towards the former.

Dying infants, while devastating, are nothing new to the Orang Asli

The R.AGE report mentioned the villagers being nonchalant about the death of a girl named Malini due to serawan, as it had become part of their life for several years already.

Looking at the researches done on Orang Asli (OA) populations in the past, a 50% chance of death doesn’t sound too farfetched. In 2010, 8.9 out of 1,000 babies didn’t make it to their first birthday on a national scale, for the OA the rate was much higher, with 51.7 out of 1,000 babies dead within a year of their birth.

The CIA estimated Malaysia’s infant mortality rate in 2016 to be 12.9 out of 1,000. In Sungai Kejar’s case, between the increasing trend of infant mortality rate and the state authorities’ records claiming that no infant deaths had occurred, the actual number of dead OA infants may well be 50% as claimed. But serawan’s not the only cause of death for OA children.

Malnutrition is a big problem among the OA community. In Malaysia, Hospital Orang Asli Gombak (HOAG) is pretty much the authority on OA health matters, and they estimated the malnutrition rate among the OA children in 2008 to be somewhere between 30-60%. In comparison, the national malnutrition rate for that year was 7.5% for moderate malnutrition (around 30-40% underweight) and 0.6% for severe malnutrition.

Another study done on a Temuan OA community back in 2002 revealed that 82% of households faced some kind of food insecurity, and more than half of the children were either underweight, wasting away or stunted. Not having enough to eat may weaken the immune system, which means that if someone didn’t die from hunger first, they’d be wide open to invasion from a host of other diseases.

However, the children in the video did not seem malnourished, so it’s safe to say that the high mortality rate in Sungai Kejar is from serawan.

What is serawan, really?

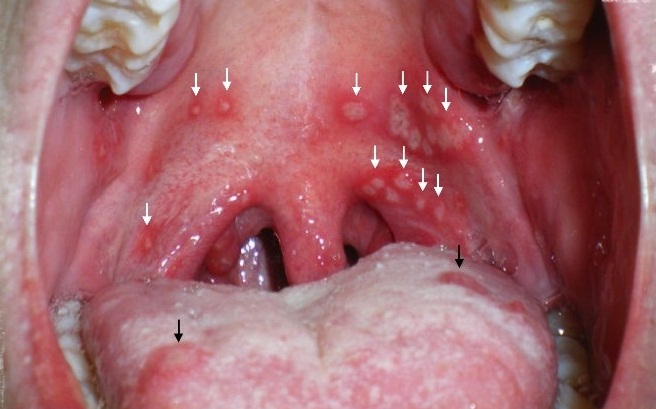

The short answer will be that no one really knows for sure. A villager described that it starts with white spots on the tongue and insides of the mouth, followed by a blackening of the throat and mouth, the inability to swallow anything, high fever, fits and finally death in a few days. It was said that serawan happens during times of haze.

Upon showing a picture of a child with serawan to a few doctors, they agreed that the white spots in the mouth was oral thrush, or formally known as oral candidiasis. In the most basic terms, oral thrush happens when a type of fungus normally found in the mouth goes berserk and infects the mouth tissues. Besides having a mouth full of white fungus, oral thrush cases are usually painless, although sometimes a burning sensation can be felt.

A lot of people naturally have the fungus that causes oral thrush in their mouths, but researchers aren’t exactly sure why it would suddenly infect some people. However, a compromised immune system can make oral thrush more likely, among other things. The condition had been seen in people with HIV/AIDS, people undergoing chemotherapy, and people with malnutrition.

Oral thrush by itself isn’t usually deadly, but it could indicate the presence of another underlying disease. So what was this underlying disease called serawan that killed the children? After the first report by R.AGE, the Perak government responded with a fact-finding mission, where a team of some 40 people went to Sungai Kejar to find out the truth.

After a 45-minute meeting with the Jahai community, the fact-finding team made it back to Gerik in time for lunch and concluded in a press conference that the disease known as serawan was actually herpangina, a viral infection that leads to painful blisters in the mouth. This conclusion was an educated guess made after interviews with the villagers.

Again, the state health department as well as the JAKOA reiterated that their statistics stand at no infant deaths in the past two years. However, they did admit that there was a problem of keeping ‘100% sure’ statistics of the OA population, as the OA move around and sometimes chose to not come forward and report deaths in their settlements.

While everything seemed to have been neatly tied up in a bow, there were a few problems with that conclusion, as the R.AGE team clearly had evidence of at least two deaths in their last report, with one death certificate. Also, herpangina (aka mouth blisters) is a self-limiting infection, meaning that it’s an infection that doesn’t spread to other parts of the body and can heal on its own. Dr. Aaron Luis, a specialist from the Sungai Buloh Hospital, had never heard of anyone dying from herpangina.

“Doctors just need to treat the symptoms with lozenges and fever medication, and the infection will heal on its own. The danger lies in dehydration, because you can’t swallow.” – Dr Aaron Luis, of the Sungai Buloh Hospital, as reported by R.AGE.

Dr Aaron also noted that the Jahai child in the picture with white growth in the mouth was suffering from oral thrush, which is not a symptom of herpangina. Also, while serawan was reported to happen during haze season, herpangina occurs all year round in tropical climates. So how did a pediatrician on that trip make an ‘educated guess’ of herpangina?

We may be going out on a limb here, but while it might have not been stated directly…

… Orang Asli are sometimes scapegoated for health problems (even if they’re not the sufferers)

In a paper co-written by Colin Nicholas, the founder and coordinator of the Center for Orang Asli Concerns (COAC), it was revealed that there was a noticeable culture of blaming the OA for health issues. In 1985, some FELDA settlers in Trolak, Perak came down with jaundice, and the health authorities responded by calling for the relocation of a nearby Semai OA village, claiming that the jaundice was caused by the Semai possibly contaminating the water with their unhygienic practices.

It turned out later that the jaundice was actually caused by insufficient chlorination at the nearby water treatment plant. While they were not the victims in this case, it turns out that the OA were sometimes also blamed for their own sickness. In 2004, four Semai children died from diarrhea and vomiting. The health authorities dismissed the incident as a case of salmonella poisoning brought on by their poor hygiene, and that they can only provide proper health facilities if the OA were to be resettled. However, the site of the incident had actually been a resettlement for years, and the real cause of the deaths was not salmonella, but a rota-virus infection.

Also in 2004, it was found that Tasik Chini had high levels of E. Coli, causing the OA in five lakeshore villages to develop rashes and diarrhea. The ministry again suggested the OA resettle in one place so they can provide better amenities for them. However, E. Coli wasn’t really the OA’s fault: the leaders of the villagers (called ‘batins’) pointed out that the problem only happened after the authorities dammed up the Chini River. A study by UKM even determined that the real cause for the E. Coli bloom was improper sewage disposal by a nearby resort as well as a national service camp by the lake side.

It might just be a coincidence, but in the serawan case the health authorities dismissed the case as herpangina just by hearing the villagers describe the disease. Disregarding the differences between the symptoms of herpangina and serawan as seen by the villagers, it might be worth noting that herpangina is caused by a virus that’s transmitted through both water droplets in the air as well as the fecal-oral route… which basically means that the virus travels from the doodie of one person to the mouth of another, through poor hygiene and sanitation practices.

Herpangina or not, it’s not hard to imagine why people living in clean, organized cities have certain perceptions about the Orang Asli. Which brings us to the next point…

The Orang Asli need help, but probably not in the way you think

As the R.AGE team had pointed out, the way most of the Jahais in Sungai Kejar get around is by bamboo rafts. If they were to try and get emergency medical help, even by speedboat and car, the nearest hospital is still two hours away.

The Health Ministry did state that they sent medical teams to the Sungai Kejar area every fortnight, but the villagers revealed that it had been almost two months since the last visit. Even when they did visit, they did not stop at every village, so the elderly and the sick struggled to travel to where the medical teams were.

The whole report by the R.AGE team may have focused on the mystery disease called serawan, but it revealed a much more sinister problem lurking between the lines. The response of the government to a deadly disease targeting children (bringing a large group of people to the village for such a short time) could have appeared ‘very condescending‘ to the Orang Asli, according to Colin Nicholas.

When asked in a different report about what the public can do to help the Orang Asli, he had said that awareness is important.

“Firstly, the public must not be gullible and must be more proactive in their reading of what is being done for the Orang Asli, the Kejar case was just one very sad case. There are other situations where people have died from water being released from a mine, or children dying of diarrhea due to poor water quality,” – Colin Nicholas, for the Star.

In a statement to the Star, Nicholas urged Malaysians to compare and contrast the facts reported in the media as well as the official statements being made in response to those facts. Listening to the authorities is not enough, as the public needs to question what is being reported.

As for charity, Nicholas had stated that the OA do not need that. What they need is to be empowered to handle their problems on their own terms.

“The Orang Asli do not need charity. We need to empower the Orang Asli so they can handle their situation and take things into their own hand. We need to engage with them, get involved with them and recognize their rights as Malaysians and as people,” – Colin Nicholas, for the Star.

In Malaysia, the Aboriginal Peoples Act of 1954 effectively sets up the Orang Asli as ‘wards of the state‘, meaning that the Orang Asli have a parent-child relationship with the government, where the government cares for every aspect of the Orang Asli’s lives, and the Orang Asli have no say in the matter.

Nicholas felt that there is a need for the public to recognize that the Orang Asli have rights as well, and to not look down on them and assume they are stupid. In fact, Cilisos did a feature earlier this year on an Orang Asli invention that possibly inspired diesel engines.The invention, called a fire piston, generates the heat needed to set tinder on fire by the compression of gas.

Even out of the engineering field, there’s no reason to believe that Orang Asli are innately inferior to other Malaysians in any way. When the public in general recognize them as equal Malaysians with rights, perhaps the future will look better for the Orang Asli.

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter18

- LinkedIn15

- Email26

- WhatsApp55