Baba Nyonyas aren’t the only Peranakans. There’re others who have their own… Qing Ming?

- 4.6KShares

- Facebook4.5K

- Twitter11

- LinkedIn14

- Email20

- WhatsApp74

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article contained some factual errors regarding the religious beliefs of the Chetti community in Melaka, which was also reflected in the title. Both the title and article have been edited to correct the mistake.

We apologize to the Chetti community for any offence caused, and would like to thank those who reached out to us to work on correcting the error.

Original article continues below.

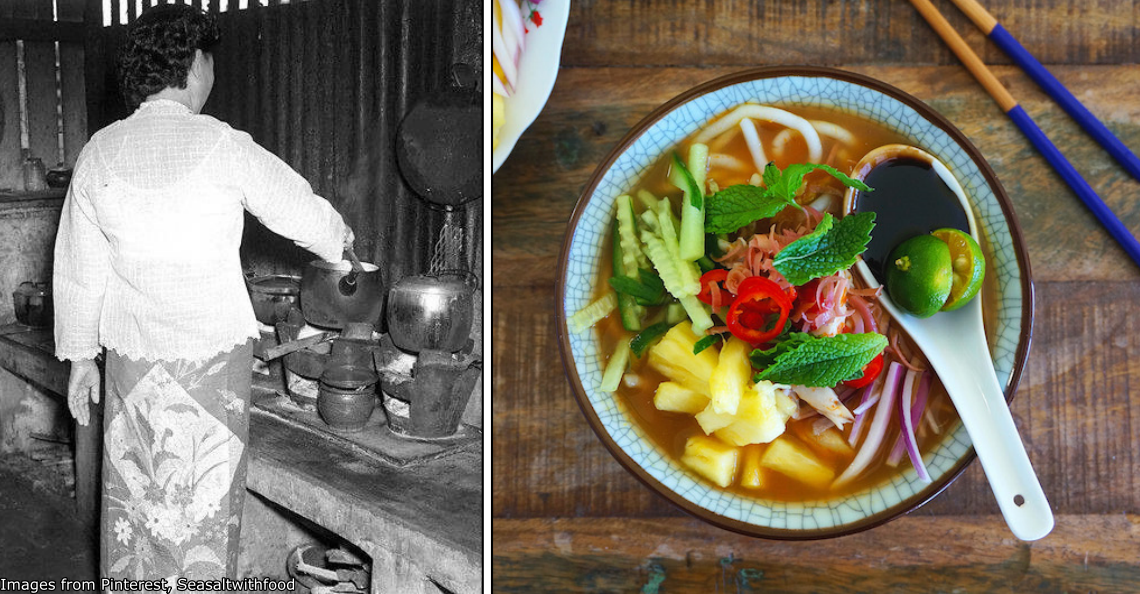

Malaysia is known for many things – our delicious hawker food, the beautiful sceneries we have (no matter mountain high or valley low) and of course, our cultural diversity. In fact, one of the most unique heritage our country has to offer probably comes from the Peranakan culture that’s gradually receiving more international recognition after getting featured at beauty pageants and Netflix series.

But here’s the thing, most Peranakan cultures featured in the media actually belong to the Baba Nyonya community. And before you say anything, yes, Baba Nyonyas are Peranakans – but not all Peranakans are Baba Nyonya. As a matter of fact, Baba Nyonyas are simply a part of the Malaysian Peranakan community.

That’s right. The term ‘Peranakan’ is a Malay word used to describe the descendants of mixed marriages between local Malays and foreign traders in the Malay archipelago. Which explains why Baba Nyonyas (aka Straits Chinese) are part of the Peranakan community, because they’re of mixed Malay and Chinese ancestry.

But most people tend to assume that Peranakans refer exclusively to Baba Nyonyas, which isn’t true, because we also have other Peranakan communities in Malaysia and their culture is equally unique and interesting as well. In fact, here are 5 cool things you probably didn’t know about the Malaysian Peranakan community.

1. Apart from Baba Nyonyas, we also have Jawi Peranakans and the Melaka Chetti

First of all, the Jawi Peranakans (aka Straits Muslims) are the descendants of local Malays and early Muslim traders of Arab, Bengali but mostly Tamil ancestry. Over time, the Jawi Peranakan community started to grow and more people began practicing Malay culture, but this assimilation also means that more Jawi Peranakans today have identified themselves as Malay instead of Peranakan.

However, despite some similarities between Jawi Peranakans and the Indian Muslim community, they’re actually pretty different. According to Jawi Peranakan anthropologist Datuk Dr Wazir Jahan Karim, while most Mamaks speak Tamil at home, Jawi Peranakans tend to converse in a mix of English and Malay.

And on the other hand, we have the Melaka Chetti (aka Indian/Hindu Peranakan) community which, similar to the Jawi Peranakans, are also of mixed local Malay and South Indian ancestry, except they practice Hinduism instead of Islam.

But despite their Indian heritage, most Melaka Chettis actually don’t speak Tamil at home. Instead, they have their own unique language of Chetti creole (like their own local dialect) which is kinda like a mix of Malay, Tamil and Hokkien. And it’s not just that, some Chetti customs are even influenced by other cultures as well, such as…

2. Naik Bukit – the Melaka Chetti version of Qing Ming

Most Chinese are known to celebrate Qing Ming, a tradition of people visiting ancestral graves and praying with food or joss offerings as a sign of respect. But it turns out, Chinese aren’t the only ones who practice that tradition in Malaysia.

Since Melaka Chetti culture is partially influenced by Chinese culture, most members of the community also perform a similar ritual to Qing Ming that they call Naik Bukit. And for those of you who got a D in your UPSR Bahasa exams, Naik Bukit literally translates to ‘climb hill’ – which, if you’ve gone for Qing Ming is basically what a lot of us end up doing whenever we visit a cemetery.

Although most people would consider graveyards to be eerie and daunting, Naik Bukit is actually seen as a joyful and lively outdoor activity in the Melaka Chetti community. And similar to Qing Ming, Naik Bukit also emphasises on the importance of filial piety, which is a Confucian value of respecting your parents and elders.

That’s not all. It turns out the Melaka Chetti community are big on ancestral worship as well cos they also practice Bhogi Parachu or Parchu Ponggal, an ancestral prayer that takes place on the eve of Ponggal. Although it’s meant as a prayer occasion, Bhogi Parachu also doubles as a family reunion as families would gather around to cook their ancestor’s favourite food and lay it over banana leaves as prayer offerings. And to make things more interesting, some Melaka Chetti families would also light red candles during prayers, just like Chinese prayer customs!

3. A Jawi Peranakan parody theatre was once banned by the British for being anti-colonial

Just to be clear, this parody theatre isn’t some Malaysian parody of Les Miserables or anything. Instead, Jawi Peranakan parody theatre, better known as Boria, originated as a tragic Persian play about the Battle of Karbala, a type of theatre known as Persian ta’ziyeh.

Although ta’ziyeh was already popular in certain parts of the Middle East and Southeast Asia at the time, it only reached Penang around the 19th century when the Indian Muslim soldiers of the British-Indian Madras army used the music during their marches.

But when Boria performances evolved from tragedies to parodies, they also became a source of mockery and challenge against British colonial powers. According to Dr Wazir, the plot of these plays typically revolve around a drunk British soldier bullying the Jawi Peranakans and Chettis. And naturally, these subjects didn’t sit well with the British and as a way to silence these protests against them, the British tried to temporarily ban Boria after the Penang Riots in 1867.

Luckily after more than 100 years, the culture of Boria continues to exists today. In fact, just last year, the Jawi Peranakan Heritage Society had submitted a proposal to the National Heritage Department of Malaysia to recognise Boria as a Unesco intangible cultural heritage (we’re keeping our fingers crossed for this one).

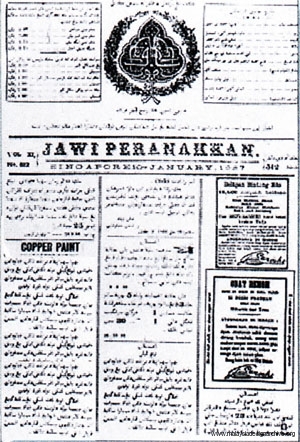

4. The Jawi Peranakans also published the first Malay-language newspaper

Back in the colonial times, most Jawi Peranakans received English education and had successful careers in banking and real estate industry while some also worked as civil servants. Thanks to the prolific influence and authority they had in society, the Jawi Peranakan community in 1876 managed to gather enough capital to establish a printing company and publish the first Malay newspaper in Malaya, Singapore and Indonesia.

Technically, the newspaper – called “Jawi Peranakkan” – was founded and published in Singapore but since Singapore was part of British Malaya back then, “Jawi Peranakkan” has been widely regarded as our country’s first published Malay newspaper.

During its run, “Jawi Peranakkan” was published once a week on every Monday at around 150 copies each print. Although it was originally intended for the Malay community (well duh it’s in Malay), “Jawi Peranakkan” also had a small-sized but racially diverse readership from Malays to local-born Muslims, Arabs and even the Malay-speaking Baba Nyonya community.

In the end, the newspaper ceased its run in 1895 after almost two decades of operation. Although it has probably become a foreign name in today’s media industry, there’s no denying that Jawi Peranakkan’s role as the pioneer of Malay newspapers have since opened many doors for Malay language publications in the region.

5. During their Hindu celebrations, Melaka Chettis have a procession that include… the Hantu Tetek

Yes, you read that right. Turns out Hantu Tetek is actually a pretty big part of Malaysian folklore, particularly in local culture where it’s believed to be a demon who kidnaps children and crushes them between its giant breasts. Fun fact: there’s also an Indonesian version of this large breasted, child abducting ghost called Wewe Gombel.

However, in the Melaka Chetti culture, Hantu Tetek is worshipped as a guardian to fight off evil spirits.

Since its establishment in 1822, the temple located in the Melaka Chetti Village has been welcoming thousands of devotees every year during the festival. And most of them would offer prayers and give thanks to the Goddess Sri Muthu Mariamman, whose powers are often linked to curing diseases like smallpox.

UPDATE 24 JUNE 2020: Yes, we heard your comments, and we’d like to apologise to the Chetti community for our oversight. We’d like to clarify that the Chetti community does not in fact worship the Hantu Tetek, and as such we’ve amended the original title of this article as well as adding this note in.

Furthermore, we also got in touch with T.Sithambaram Pillay, a member of the Melaka Chetti community, who told us that the Chetti community in fact worships the Hindu Gods and Goddesses. In relation to the feature of the Hantu Tetek, it makes an appearance during the Sri Muthu Mariamman Thiruvila celebration. A procession is normally held, and on the last day of the procession, the deity Mariamman will be decorated and perched on top of a ‘rathma’ (a chariot of sorts). The Hantu Tetek will join in the procession, but it’s role is to absorb the negativity around the procession.

Sundaram Padiachee, the Community Management Committee responsible for Cultural Promotion and Preservation of the Melaka Chetti added that the Hantu Tetek – which is called ‘Bhootam’ in Tamil – wards off wandering evil spirits to allow devotees to conduct their prayers in full reverence to the Goddess.

Today, the pair of Hantu Tetek (male and female) have become an icon for the community. They make their appearance at social events or in welcoming honored guests to the Village, adding color and gaiety to showcase the Melaka Chetti heritage.

But sadly, Malaysia is slowly losing these Peranakan cultures

Unfortunately, like most minority groups out there, the Chetti and Jawi Peranakan culture are at risk of losing their heritage cos the younger generation of Peranakans are gradually losing touch with their identities. But what makes this news sadder is that although there are still tons of Peranakans around Malaysia, the culture is still in slow decline.

Thousands of the Jawi Peranakan families are still around but they don’t call themselves Jawi Peranakan anymore, they just call themselves Malays. The children are called Malays. Like the Chinese Peranakan, they call themselves Chinese. – Dr Wazir, as quoted from MalayMail.

So maybe what we can do as an effort to preserve this uniquely Malaysian culture is by visiting more Peranakan museums and learn more about their culture. And with all the recent media buzz about Baba Nyonya culture, 2020 seems like a pretty good time to explore these lesser known sides of Malaysian Peranakan cultures too.

If you enjoyed this story and want more, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group🙂

- 4.6KShares

- Facebook4.5K

- Twitter11

- LinkedIn14

- Email20

- WhatsApp74