Malaysian journalists have been banned from Parlimen lobby. This might change the news you read

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.5K

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn5

- Email8

- WhatsApp27

Whenever parliament is in session (like now), it’s usually a common sight to see reporters from all news publishers hanging around the Dewan Rakyat lobby, waiting for the doors to open and for the MPs and ministers to come out. The minute the doors swing open, there’s a flurry of activity as they rush to these MPs, asking questions and recording replies – kinda like this:

But when I dropped by in Parliament last week, things were strangely quiet.

I had just delivered some sweet tangy CILISOS cilisos to Ooi Heng of KPRU, a parliamentary research institute whose office is in the parliament building. Ooi Heng was nice enough to take me on a tour of the newly-renovated Parliament building, which included a walk past the lobby of the Dewan Rakyat (that was in session at the time). That was when I noticed it was a little emptier than usual… where were the reporters?

An estimated two-minute walk later, I answered my own question – The reporters have been placed in a special media room, on a different floor, away from the lobby. In the room were several TVs displaying the live feed from Dewan Rakyat, and a podium was set up for MPs to give speeches and take questions. In fact, Rafizi Ramli was in the middle of speaking when Ooi Heng and I walked in:

This is because just the day before, Dewan Rakyat Speaker Tan Sri Pandikar Amin invoked Standing Order 94, which is a subliminal command programmed into Clone Troopers to betray their Jedi Commanders in order for Palpatine to… -No wait, that’s Order 66 from Star Wars. Standing Order 94 is actually part of a list of procedures that govern how the Dewan Rakyat is run – in this instance giving the Speaker authority to give (and revoke) permission for journalists to attend sittings, as well as make certain rules for journalists to follow. And in case you’re wondering, a Speaker is basically the person who runs the Dewan Rakyat while it’s in session.

Naturally, the some people (mostly reporters) weren’t happy about this, but while you might be wondering why we’re writing about what’s essentially a tiff between the bureaucracy and the media, the effects of this ruling may be farther reaching than you might think. This will become clearer once we look at the points of view from those who support the ban, as well as those who oppose it.

Let’s start with the official reason for the ban, which is…

Parliament doesn’t want reporters loitering around and harassing MPs

According to Tan Sri Pandikar, several MPs had complained about the reporters hanging around the lobby. This was for two main reasons, the first being that reporters in the lobby quite menjolok mata – not in the way you’re thinking, but because the sight of reporters hanging around the lobby was sort of an eyesore:

“I see the media people sitting like there is a picnic.” – Tan Sri Pandikar Amin, as quoted by The Star.

The second reason was that reporters in the lobby suka menjolok MP. Not in the way you think (shame shame), but referring to how recording devices are pointed at (menjolok) MPs when recording their statements. Apparently, some MPs were annoyed or discomforted over the media chasing them down for statements the moment they leave Dewan Rakyat – with some of them not able to even use the toilet in peace. While Tourism and Culture Minister Datuk Seri Nazri promised to look into un-banning them, he also said that some ministers don’t appreciate getting ambushed for statements on sensitive matters:

“… [You] must understand, as a minister probably there are things we don’t want to reveal to you and we don’t want you to ambush us like that.” – Datuk Seri Nazri Abdul Aziz, as quoted by The Malay Mail Online.

Tan Sri Pandikar also stated that his decision was also made in consideration of safety of the MPs and ministers, which may be put at risk in the reporter rush. Datuk Seri Nazri mentioned that there have been instances where outsiders pretended to be journalists in order to approach MPs and hand over letters:

“The security threat is not the media, but it is the non-media personnel who take advantage of the situation to approach lawmakers, especially the ministers. -Datuk Seri Nazri Abdul Aziz, as quoted by The Malay Mail Online.

But of course, not all MPs supported the idea. On the day it was announced, some MPs like PAS’s Datuk Mahfuz Omar and DAP’s Seremban MP Anthony Loke argued against it. Parti Amanah MP Raja Kamarul Bahrin even suggested that the decision might have been to intentionally make it harder for the media to talk to Opposition MPs:

“I feel like this is a subtle move by the government to limit opposition MPs’ access to the media and vice versa.” – Raja Kamarul Bahrin, as quoted by Free Malaysia Today.

This kinda brings us to the other side of the story… from the reporters’ point of view –

Reporters feel they’ve been prevented from doing their job

We spoke to two reporters with experience in covering parliament stories – Ram, who is also Secretary of the Institute of Journalists Malaysia (IoJM), and one who prefers to remain anonymous; so we’ll name him Tintin after the popular comic character.

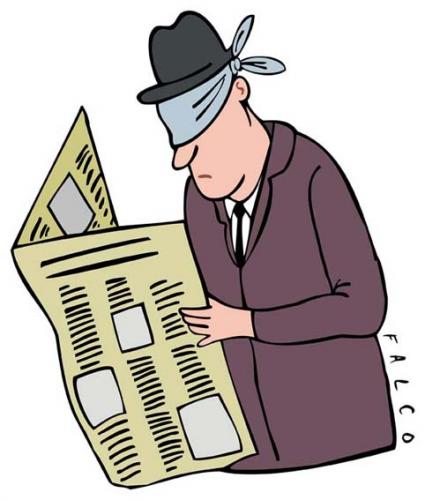

The problem for many journalists in Malaysia is that access to information can sometimes be restricted or hard to come by:

“One of the biggest problems faced by Malaysian media is access. Certain media organizations have been denied access to some government offices and even some Opposition press meets [while some] holders of public office and lawmakers do not regularly issue media statements and sometimes even evade the media.

In that sense, Parliament has done a fair job of providing all media equal access to all lawmakers and holders of public office.” – Ram

Both Ram and Tintin tell us that the parliament serves as an important access point to get statements from MPs or ministers on pressing issues that they might never talk about otherwise:

“The lobby is the best place to jolok MPs who don’t otherwise want to talk to the media. [With the new restrictions] MPs and ministers can easily evade journos who need questions answered.” – Tintin

This eventually filters down to ugaiz – the people who depend on these journalists to get information on what’s happening with the country because, really, how many of us get regular updates, or get to talk to our ministers and lawmakers on a regular basis? An MP in BM is Wakil Rakyat, meaning that they’re a representative of the people. This means they’re accountable for the decisions that they make in Parliament.

So when there are questions about why your MP decides to support or reject a Bill that may potentially affect your way of life (like Hadi Awang’s Akta 355 amendments) it’s really up to the journalists to ask these questions on your behalf in order to help you decide if you’d still want to vote for the same MP in the future. So really, when it comes to chasing down MPs for statements, it can be argued that it’s part of the reporter’s job to get answers:

“The job of a journalist is to make a public official’s life not easy by asking questions that serve the people of the country. A journo who doesn’t ask hard questions should just quit because they’re not doing their job.” – Tintin

So with both sides of the story a little clearer, the next question would be…

What is Parliament like in other countries?

One thing that Tan Sri Pandikar mentioned when questioned about his decision is that reporters in other countries don’t behave like Malaysian reporters do while in Parliament:

In other Parliament, YBs, it is not like the Malaysian Parliament whereby the minister, upon exiting from the debate session, is immediately shoved with microphones. No such thing …” – Tan Sri Pandikar Amin, as quoted by The Malay Mail Online.

So out of curiosity, we decided to take a look at how it’s done in some other countries.

In Australia for instance, their version of the Standing Orders acknowledge the role of the media in informing the public of what’s happening in Parliament, and have set up specific rules (automatic download warning) and places where recording is allowed. For instance, media activity is prohibited in the Parliament lobby and dining areas, but interviews are allowed in other places as long as there’s consent and not blocking an entrance. A media gallery is prepared for journalists to watch parliamentary proceedings and for MPs to have press conferences.

In contrast, the United States uses a different system whereby all media activities are handled through a dedicated press office (usually called a Press Gallery). This office will coordinate all information, updates, working spaces for journalists, and requests for interviews. The House of Representatives (Dewan Rakyat) and Senate (Dewan Negara) have their own Press Galleries and an internal news team which provides updates on what’s happening during discussions and votings – including who voted for or against a certain Bill. We should also note that early last year the Missouri state Senate also came under fire for moving reporters to a working space on a different floor, as well as sending a memo to reporters asking them not to chase down senators for interviews. If you read the article discussing it, you’d find very similar arguments to what you’ve just read in this article 😐

But what’s really interesting is what’s happening in Poland, where the government’s decision to ban all recording of parliamentary sessions (except by 5 selected TV stations) and to limit the number of reporters allowed in Parliament led to a wave of protests against the ruling party – not just by journalists and citizens, but also by Opposition MPs who blocked access to one of the halls. Eventually, the Prime Minister had to be evacuated from Parliament.

In the 27 years of Poland’s democracy, journalists have been a constant presence in the parliament’s halls. Banned from the main assembly room, they can grab politicians for interviews in the halls. – Quoted from The Telegraph.

Again, if you read the article about it, you’d find some pretty familiar arguments as well. Oh, and the ban was eventually lifted.

Can the Parliament and the media come to a compromise or something?

While Ram agreed there there have been times where certain media might have been overzealous at getting comments, he stressed that barring and restricting the media is not a solution. Instead Ram suggests that something like security zones can be established for privacy while still allowing journalists access to MPs. On the other hand, Nazri is suggesting that a space be set up in the lobby for MPs and ministers to go to when they want to speak to the media.

But whatever the suggestions may be, perhaps the root of the problem stems from a lack of communication between politicians, government departments, and the public (via the media or otherwise). As an example, there’s no record of how each individual MP votes on a certain Bill. In fact, our friend Sze Ming at the Sinar Project had to resort to watching videos of the Prevention Of Terrorism Act vote to physically count it herself – which she tells us took 5 hours to do.

Even for a two-sen blog like CILISOS, we can attest to the number of times we’ve played telephone musical chairs whenever we call certain government departments or just totally not received a response at all. And these aren’t even for hard-hitting questions. In comparison, when we emailed the US Department of Justice asking them why they didn’t name MO1, we got a reply within 3 hours!

So while there can be rules keeping journalists away from MPs and ministers, it might also be a good time to start looking into improving the channels of communication between the media and the government to balance things out – especially during a time when our press freedom scores are gradually worsening by the year.

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.5K

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn5

- Email8

- WhatsApp27