Here’s how Malaysia became the rubber (and condom) capital of the world.

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter12

- LinkedIn20

- Email11

- WhatsApp42

If we were to ask a random person to name something Malaysia is known for, common answers could be the KLCC, traffic jams, or the food. Perhaps not many would think of the thing that people put on their M. Night Shyamalamaladingdongs before doing some serious waterbending.

That’s right, we’re talking about condoms. We’ve seen some weird (but very real) Malaysian-flavored condoms in the past two years, like the durian condoms in 2016, the nasi lemak panas condoms in 2017, and very recently, the teh tarik kurang manis condoms. All of them are from the brand ONE, whose condoms are manufactured by the biggest condom makers in the world, the Malaysian-based Karex Berhad.

They make around five billion condoms every year, commanding a 15% share of the global market.

“*jokingly* Imagine the world without condoms. If the world has a population of over seven billion now, it could soon be 10 billion because there’s no way of preventing conception. So again, our rubber has performed a great duty for humanity,” – Tun Dr Mahathir, Prime Minister, as reported by the Star.

It’s common knowledge that Malaysia was at one point the biggest rubber-producers in the world, so it might not be surprising to some people that we have both the biggest condom makers as well as the biggest rubber glove makers today. But why rubber in the first place? That’s a question worth pondering, especially if you consider that…

Rubber was practically useless before the 1800s

First of all, rubber is not an originally Malaysian plant. The kind of rubber we produce are from the Para rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), which, as its name implies, can originally be found only in the jungles of Brazil. Rubber was basically unknown to the rest of the world until French scientist Charles de la Condamine discovered it in 1735. It took several more decades until it became known as ‘rubber’, when an English guy discovered that it can ‘rub’ off pencil marks very well.

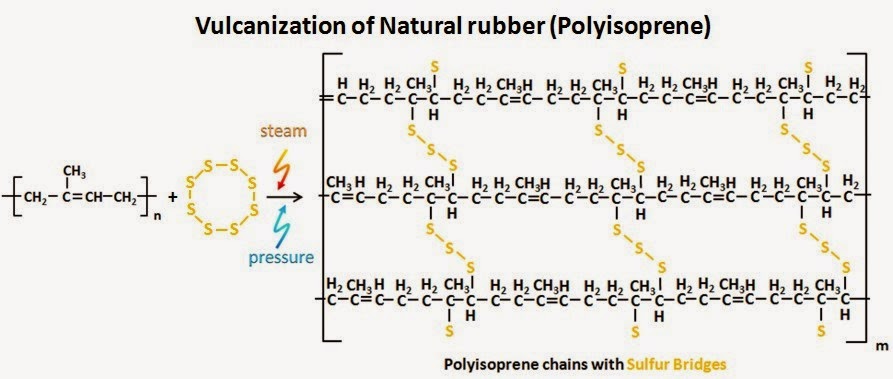

Other than erasing and making bouncy balls, rubber wasn’t much use back then. Natural rubber is soft and sticky when the weather is warm and became brittle and cracked when it’s cold. But an American inventor named Charles Goodyear saw potential in the substance, and after years of throwing rubber into different chemicals, he discovered in 1839 (by accident) that heating rubber and sulfur together makes it stronger, even when hot.

Goodyear called this process ‘vulcanization‘, after the Roman god of fire. With stronger rubber available, in 1888 pneumatic tires (rubber tires with air in them) became a thing, making rubber a highly wanted resource.

However, supply was very limited at that time. The only way to get rubber was from wild rubber trees in Brazil, and these are dispersed throughout the thick Amazon jungle. Brazilian rubber tappers had to first spend time finding a rubber tree, but once they’ve found it their tapping method often killed the tree, so they had to constantly look for new trees. The South American leaf blight (a local tree disease) hampered plans of a plantation there, so to keep up with the demand…

The rubber industry was ‘stolen’ from Brazil by the British

Sometime in the 1870s, a British explorer by the name of Henry Wickham claimed to have performed a heist that changed the course of world history. The British government was said to have sent him on a mission to bring back rubber seeds from Brazil and deliver them to Her Majesty’s Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew, London. So Wickham went into the jungles of Santarem, Brazil, collected around 70,000 seeds from there, loaded them up on his ship, and made off, presumably with Jack Sparrow’s theme song blaring out of the ship’s gramophone.

Some had said that Wickham’s act wasn’t really a heist, with an NYU professor saying that Wickham had ‘inflated this trifling errand into an act of derring-do‘. Also, Brazil’s export laws at that time had not prevented what Wickham did, but some said that he may have lied a little about his cargo to get an export license from Brazil, so… was he a liar, or a stealer? No one knows for sure.

Regardless of that, the rubber seeds made it to the British’s labs, and these were germinated and sent to its Asian colonies to be planted. This effectively ended Brazil’s monopoly on rubber, and changed the future of several British colonies, including Malaya.

“In 1913, the rubber from seventy thousand seeds smuggled from Brazil and planted in Britain’s Asian plantations flooded the market, outselling the more expensive “wild” rubber and tossing it from the stage. The bust dealt the Amazon Valley a blow from which it never recovered: In 1900, the region produced 95 percent of the world’s rubber. By 1928 … the Amazon produced barely 2.3 percent of its needs.” – Excerpt from Joe Jackson’s “The Thief at the End of the World“.

In colonial Malaya, rubber wasn’t popular with the people until a botanist named Henry Nicholas Ridley came into the story. Ridley was convinced that rubber could be just as lucrative as coffee as a plantation crop, so he spend so much time and effort convincing the locals to plant it (some said by stuffing rubber seeds into the pockets of everyone he met) to the point that people started calling him ‘Mad Ridley‘. Well, sticks and stones may break his bones, but along with tin…

Rubber practically changed Malaysia’s history

One of the first rubber trees in Malaysia was planted in Kuala Kangsar in 1877, and by 1930 Malaya’s rubber industry had dwarfed Brazil’s. While the British had started rubber plantations in their other colonies as well, several factors pushed Malaya to the top when it came to rubber.

In terms of climate and soil, Malaya was just as suitable for rubber as India, Thailand and Indonesia. However, its location on the trade route and its relatively smaller size gave it an advantage: there’s less distance from the plantations to the ports, so transporting rubber was a lot cheaper in Malaya. Ridley also discovered the herring-bone method of tapping, which, instead of killing the tree, made it gush out more rubber over time.

While in the beginning investors in Malaya focused on tin mining, many of them realized that tin will run out eventually, but rubber can potentially be forever (technically about 25 years, but you can plant new trees). So Chinese and European investors switched to rubber, and by 1921 rubber plantations covered 1.34 million acres of Malaysia (mostly Malaya), which was over half of all rubber plantations in both South and Southeast Asia.

To run these plantations, the planters brought in foreign workforce by the boatloads: Europeans looked to South India for labor, and Chinese planters depended on the ‘coolie trade‘ from South China. These migrant communities populated the areas where tin and rubber were mined and planted, which were mostly on the west coast of the Peninsula, closer to the ports. Because of all of these factors, the Peninsula’s west coast soon transformed with regards to economy, racial composition and infrastructure development (like roads, trains and ports), changes that can perhaps still be seen today.

But things didn’t stay rosy forever. Between 1980 and 1990, a global recession happened, which resulted in lower demand and prices for all of Malaysia’s major exports, including rubber. One can say that this spelled doom for those in the rubber business, but…

Some Malaysians turned this adversity into opportunity

Due to the recession, many people in the rubber industry had to turn to other things to survive. Some went into palm oil over the years, which was more profitable and less labor-intensive, while others built on their rubber and started manufacturing rubber-based products, like gloves for both hands and tinky-winkies alike.

Among the people affected by the recession included the Goh family, the people behind Karex Berhad. The Goh family first came to Malaysia during the rubber boom, but instead of rubber their first business was a sundry shop that catered to people in a rubber estate in Johor. Customers would sometime trade rubber sheets for their wares, so the second generation, Goh Huang Chiat, expanded into a rubber-processing factory, and eventually became wealthy enough to send his children for tertiary education.

However, during the mid-1980s global recession, Huang Chiat went bankrupt due to rubber prices plunging overnight. In light of the rising HIV/AIDS epidemic, they decided to go into the condom business, so the family sold their homes and used that money for a new condom factory. They even built one of their first condom-making machines from scratch, possible due to two of Huang Chiat’s sons (Goh Siang and Goh Leng Kian) having studied chemical and mechanical engineering.

“He (Leng Kian) told me he could build machines and I never believed him. I mean, talking about machines with moving parts and all … these were things only ang mohs could build… So, when I saw what my uncle could do, I was impressed and then realized what human beings are truly capable of. And when we succeeded in making a condom machine that met our needs, things began to really change.” – Goh Miah Kiat, current head of Karex, in an interview with Options.

It was slow going at first, with the family having had to stay in a room above the factory for a few years, things started looking better. But what really put Karex on the global map was their business strategy, which involved pitching to governments and institutions like the UN and the World Health Organization (both were involved in fighting AIDS) rather than individual retailers. Karex bloomed, with government tenders making up about 46% of their sales, 51% coming from manufacturing condoms for other companies (like Durex), and the remaining from sales of their own brands of condoms, Carex and INNO.

From a family business that makes 60 million condoms a year from their home/factory, today Karex employs some 2,000 people, has factories in Johor, Selangor, and Thailand, and makes more condoms per year than any other company in the world. So now that you more or less know the history behind condoms and rubber in Malaysia, you can thank all the people throughout history that made it possible the next time you pop open a condom.

- 1.5KShares

- Facebook1.4K

- Twitter12

- LinkedIn20

- Email11

- WhatsApp42