No internet. No chemo. Here’s how different it was getting cancer in Malaysia in the 1980s

- 738Shares

- Facebook614

- Twitter19

- LinkedIn20

- Email28

- WhatsApp57

Cancer is consistently the third most common cause of death in Malaysia. But you probably knew this already.

What’s strange though, is that these rates actually seem to be increasing. Between 1988 and 1990 – there were less than 57 cases of cancer per 100,000 citizens of Malaysia. Today, the incidences of cancer have almost tripled in frequency (!).

You’re more likely than ever to be diagnosed with cancer (but it might not be cancer’s fault)

While incidences of cancer have gone up, that might not necessarily be because cancer is more rampant, it could be because we’re living longer (and have to die of something in the end), and we’re getting better at looking for it. Thankfully, one of the advantages of finding the cancer is that you have a better chance of treating it. However, those treatments aren’t getting any cheaper.

“Medical inflation in Malaysia has been estimated to increase to about 10 to 15 percent annually and based on statistics from the past 15 years, the medical inflation rate has increased by a whopping 107 percent.” – HowToFinanceMoney.com

This has led to 48% of those diagnosed with cancer spending more than 30% of their household income on treatments. This is why Prudential has released a new, specific cancer plan, aimed to reduce those burdens – introducing PRUcancer X.

In a nutshell, unlike a normal critical illness plan, this one’s made specifically for cancer – so Prudential can afford to cover you more, for less. For as little as RM400* a month, you can qualify for minimum coverage of RM250,000, including compassionate benefit.

While costs are going up, treatments, diagnosis and coverage are getting better, resulting in a very different landscape of cancer than we had before. So we thought it would be useful to see how far we’ve come. We teamed up with Prudential to ask a few Malaysians what having cancer (or a relative with cancer) was like 30 years ago.

To add some useful context, we spoke to Malaysian Oncological Society president Dr Matin Mellor Abdullah, and Dr. Nirmala Bhoo-Pathy, an associate professor at the Faculty of Medicine at University of Malaya, studying cancer outcomesin Malaysia.

1. In the 80s, it wasn’t normal to follow up cancer removal with chemotherapy

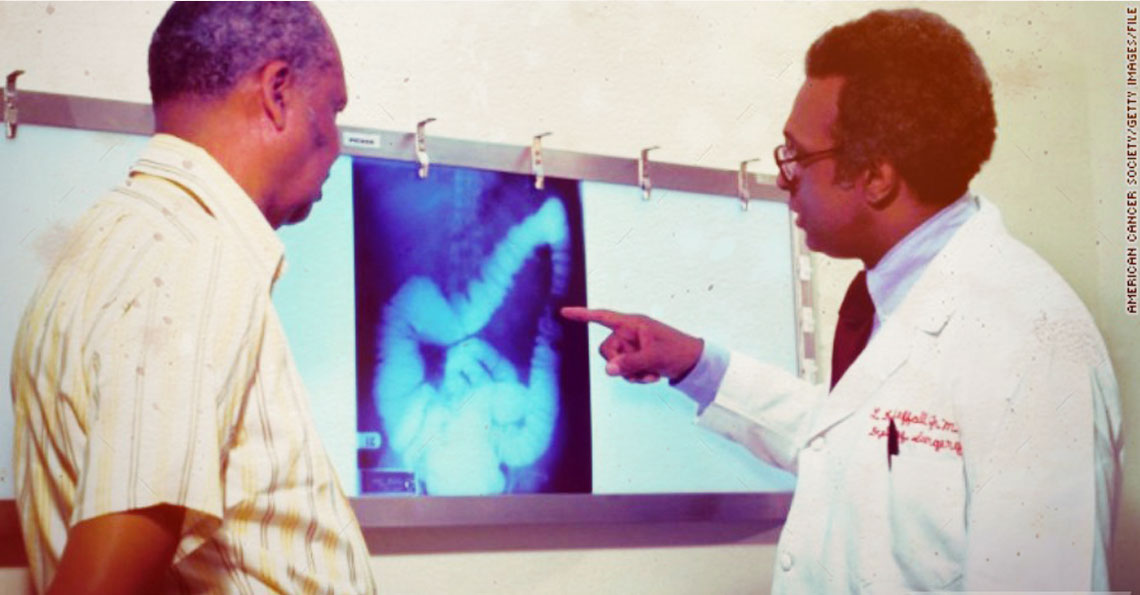

While visiting a friend in the hospital in 1986, Robert’s daughter noticed that he was frequently visiting the bathroom, almost every hour without fail. Suspecting something was amiss, she encouraged him to go for a scan. They found a tumour around the end of his colon, and part of his rectum.

This was his second cancer – the first one – a case of nose cancer five years earlier had been treated by radiotherapy and did not re-emerge. This time however, the cancer was more serious – Stage 3. An operation was done to remove his rectum immediately, with a second colostomy to remove fecal matter. After that, he was prescribed antibiotics and painkillers to recuperate.

“We were the ones that brought him to the hospital, and after the surgery, the doctors said there were no traces of cancer, so we didn’t know that anything else was necessary.” – Robert’s daughter

However, a few months later in June, the cancer was found to have spread to his lungs, and a few months after that, to his liver. At that point, not much could be done, and he was given painkillers to manage his quality of life, and he passed away quietly a few months later.

How it’s changed

Today, Dr. Matin tells us that chemotherapy and radiotherapy are not just recommended after surgery, but BEFORE as well.

“In fact in some times, if results are good, you might not even need surgery. The guideline is actually to run chemotherapy before surgery to shrink down the cancer, alleviating the need for surgery. After the surgery, we still want to reduce the risk of relapse and surgery by using chemotherapy and radiotherapy.” – Dr. Matin

2. Before the internet, a well-read family saved itself from misdiagnosis… with books!

In 1996, while in the shower, Juliet’s mother noticed a small 50sen-sized lump on her breast. Back then, Malaysia had just started stressing self-examination.

“In Malaysia, there are no population-based cancer screening programs before 1995. Started from 1995, government launched cancer prevention campaign and stressed breast self-examination (BSE) and yearly examination for women aged 20 years and above (Chan, 1999).And in the same year, the pap smears was extended to all women who have been or are sexually active and are aged 20-65 year” – Improving QoL among Cancer Patients in Malaysia, Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, Vol 13, 2012

They took her mother to a small hospital in Melaka for a mammogram, but the doctors found nothing. These days, people would probably research online for alternatives, and yes there were already the beginnings of the internet in 1996, but at the time, there was precious little information online (remember Jaring?). Thankfully, Juliet’s family is quite special.

“Many of my family members have health issues, so we always buy books to read about our problems – we are resilient people, and we check problems and try to find out on our own. Through our issues, we also know a lot of medical professionals.” – Juliet

From those books and consultation, Juliet suspected that the Melaka hospital might have done a mammogram at one corner, with the tumour being in the other corner. “But my mom could feel it – she touched it and felt the lump there.” So they opted for a second mammogram, this time from their family doctor in Subang – and they detected a tumour there. They then surgically removed it, and found that it was malignant, and had also affected the lymph nodes (which can spread cancer to other parts of the body), and carried out a total mastectomy to ensure the right breast would not be affected.

“After the surgery, all the doctors recommended chemo, but we had done our research – my great grandma also died of colon cancer which spread to her bones. Because of chemo, it weakened her and that’s why we reckon she passed away. So we sent her to Singapore for a second opinion” – Juliet

The Singapore hospital recommended an alternative – 5 years of hormone therapy, and based on Juliet’s family’s own research, they concurred.

“My mom is a very happy go lucky person, and 5 years of regular checkups, and the results were very good, so she’s cancer’s free at 70.” – Juliet

How it’s changed

While many many more Malaysian women perform breast self-examinations now, mammograms have also improved vastly in their accuracy, due to new technologies. While they were previously more like 2D X-rays, today – they can now take a 3D image of your breast, load it onto a computer, allowing a doctor to find tumours with much more granularity. However, they still miss a large portion of tumours.

“Today, we usually combine mammogram with ultrasound, and if we find something suspicious, an MRI is standard practice today for any decent hospital.” – Dr. Matin

But actually, the biggest difference with patients today is that they no longer need to look at books. Because we have the internet! Woohoo! NO need doctor adi! When asked about how the internet has changed cancer, Dr. Matin simply pointed to this mug, on his bookshelf.

“The problem with the internet is it’s a double-edged sword – there are a lot of blogs and stuff. If what you’re reading is backed by scientific research. But there are plenty of sites with words like “our research has shown”, which gives a false sense of security. At the end of the day, the physician is best suited to diagnose the patient. Having said that, patients can always get a second or third opinion for peace of mind, but from professionals. I would do the same. But relying on resources that are not proven is dangerous.” – Dr. Nirmala

One thing that both doctors agree on is that the internet has definitely helped oncologists to be more knowledgable and up to date. Dr. Matin used to go to Universiti Malaya’s medical faculty a few times a month to research a patients conditions and related cases in medical journals.

“If we ever have a patient we aren’t sure, we would go to research more a few hours. These days, we can access those things from my laptop – you still the work, but you can do it at home.” – Dr. Matin

“Many doctors subscribe to a platform called Medscape – when there are new developments, drugs and theories – and we can forward these credible sources along to our colleagues – there’s better sharing of information. There are international guidelines for breast cancer for instance – but again, some clients have cost issues, or deviances in terms of their specific condition. Every country also has guidelines that are more resource-optimised based on what’s available, and what the general level of income is in that country.”- Dr. Nirmala

3. The father who had carried an experimental chemo kit on his shoulder

In the early 1990s, Mr Lai had indigestion. When he went in for an endoscopy in his hometown of Ipoh, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. The family went down to KL to have 3/4 of his stomach removed. While they didn’t have insurance, they were thankful that the company he worked for settled everything, even getting his own single room for two weeks to recuperate.

After the two weeks, the doctor recommended an aggressive course of chemo, to be administered with an experimental (at the time) chemotherapy device, which slings on to his shoulder, and regularly pumps the chemicals into him. Once a month, he would take it back to change the battery and refill the fluids.

“The doctor recommended an aggressive course of chemotherapy, and we agreed. 20 years ago is not like modern now. No Google, no WhatsApp so we just trust what the doctor says.” – Madam Chin, Mr Lai’s widow

While the device was cutting edge at the time, the chemicals were harsh, and he vomited alot. His appetite was bad, but he still dutifully slung the device over his shoulder wherever he went. One day, it actually stopped, and Madam Chin recalls panicking, and driving down to KL to get it fixed immediately.

Mr. Lai even went back to work for a while at an office near the Ipoh turf club. However, he said the fumes made him tired, so his well-meaning boss allowed him to work from home. However, the chemotherapy drained him massively, and eventually he had no choice but to resign. Mr. Lai was scheduled to do a 6 month course, but halfway, he stopped chemotherapy because it took its toll on him, he was drained out, and his hair was falling aggressively. At that point, the tumour was still growing aggresively, and the doctor told him he had 3 months to live.

“It was really rough on him. He became like a feeble 90 year old. Tough on us also, because he was a very strong and capable man” – Chee Seng, Mr. Lai’s son

Amazingly however, on a course of Chinese medication, a positive mindset and a total change in lifestyle, he made it past the 3 month mark. Wayyyy past. Madam Chin made a point of writing every single medication he took in a booklet (she’s since thrown it away), just for reference.

“I remember him saying. “The doctor gave me 3 months, but God gave me 13 years“” – Madam Chin

How it’s changed

Apparently, doctors telling you how long you’re gonna live doesn’t happen anymore.

“The first advice to any oncologist is NOT to give any timelines. It’s not in the doctor’s position – we can talk about general time frame of survival, based on cases. We’ll say “OK, a stage 4 breast cancer, 50% of patients survive for one year, the rest survive longer.” Having said that, stomach cancer prognosis is very bad.” – Dr. Matin

Amazingly, these portable chemotherapy devices still exist, although they aren’t very common still. Also, Dr. Matin shared that the horrible side effects Mr. Lai suffered were common with the drug (either cisplatin or 5FU) probably had in the kit.

“We don’t do that anymore these days – if we talk about quality of life and convenience, it’s not there. Today, chemotherapy protocols have changed. Today, the same chemicals can be infused over a period of 2 days. Continuous infusion is something that people have moved away for a long time now – for convenience and side effects. You can’t exercise, you can’t interact. And now there are oral chemotherapy pills (like oxaliplatin, or TS1 or xeloda), so you just pop them twice a day, rather than carry a massive device” – Dr. Matin

One thing that Dr. Nirmala mentioned hasn’t changed though, is that patients will most likely have to come to a big city to get proper cancer treatment – there are currently a few centres in Penang, one in Johor, another in Kuching, and of course, several in KL.

Alas, companies aren’t as generous as they used to be. Dr. Matin shares that while most patients have company insurance, the payout limits are usually not enough to cover cancer treatments, usually RM30-50k.

“IF you have been working for GLCs for years, then coverage is sometimes unlimited, but those are being phased out. There was one gentleman retired from a GLC, and he’s getting medication costing RM30k a month, but that’s those days la. Nowadays, it varies.” – Dr. Matin

And the cost of cancer isn’t just… cancer.

CILISOS has written extensively about the cost of cancer in Malaysia before, even covering the differences between public and private healthcare (that’s a conversation for another day), but apparently, there were many things that we didn’t quite cover.

“In Malaysia, non-medical costs are very important as well – travel to and from hospitals – people coming from outstation because most of the cancer treatments are in KL. Then they have to get someone to take care of their child, some people need to buy a wig for their hair, physio therapy, dental care, parking fees. These things really add up.” – Dr. Nirmala

On top of that, there are other things that people don’t take into account, such as caretaker costs, alternative treatments, and plans that don’t cover things like overseas medical expenses. And of course, there’s the big one – loss of income, which can be financially devastating for many Malaysians.

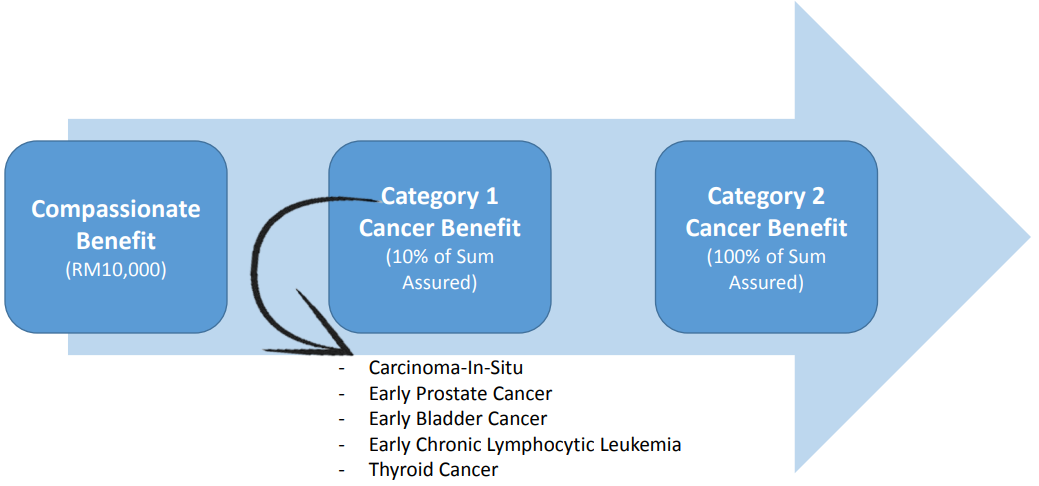

This is why Prudential created PRUcancer X – a cancer plan that pays out regardless of the costs you incur. In an early stage, you’ll get 10% of the total payout (up to RM2 million depending on the plan), and at the unfortunate later stages, you’ll have access to the entire sum assured; and in the unfortunate event of death, an RM10,000 compassionate benefit.

When cancer hits, the range of concerns isn’t all that different from 30 years ago – disagreements on the treatments, caretaking responsibilities, loss of income and of course, costs. So it’s probably not a bad idea to remove one of those concerns today 🙂

Or hey, if you want to forego those responsibilities and get a rocket pack wheelchair? Well, that’s another option available today that wasn’t there before.

- 738Shares

- Facebook614

- Twitter19

- LinkedIn20

- Email28

- WhatsApp57