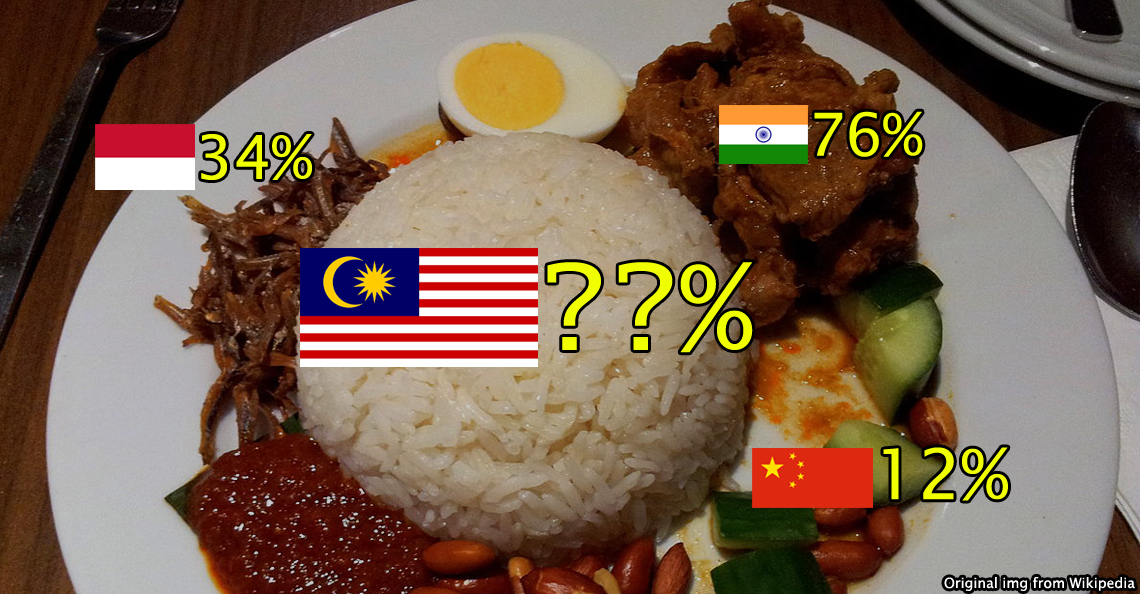

What percentage of your nasi lemak is imported? See if you can guess.

- 762Shares

- Facebook721

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn8

- Email10

- WhatsApp17

When it comes to nasi lemak, we Malaysians have a sort of borderline fetish for it. It is, after all, the dish commonly pictured when you talk about Malaysia’s national food. It became the inspiration for a certain Miss Universe’s dress, and we’re pretty sure that someone, somewhere at some point have got off to the smell of fragrant coconut and pandan rice.

Yes, nothing says ‘Malaysian’ like a steaming hot plate of nasi lemak. But how much of it is made of local, Malaysian ingredients? Well, you might be surprised to know that…

As much as 37%-46% of our nasi lemak may not be of Malaysian origin at all

Question: how can you tell if the rice you’re eating is local or not? At first, we tried asking a cafe operator and a caterer if their ingredients are local. However, both have stated that they’re pretty clueless themselves, as their ingredients are usually bought at a wholesale market.

Knowing for sure where each ingredient of a particular plate of nasi lemak from a particular eatery comes from would require tracing each of them up the supply chain, and even then they might not be representative of the nasi lemak at other eateries. So how? Well, here’s our strategy.

- Step 1: Figure out the ingredients of a generic nasi lemak, and how much they contribute to the dish.

- Step 2: Figure out how much of each ingredient is imported, and how much is local.

- Step 3:

ProfitCombine the local percentage of each ingredient to find out the local-ness of the nasi lemak as a whole.

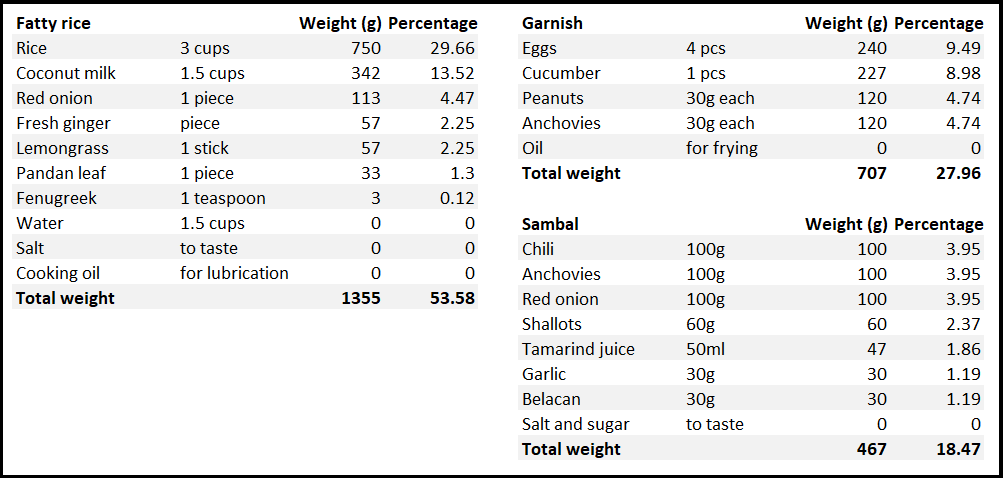

Step 1: The ingredients

For this article, we’re referring to the ‘Classic Nasi Lemak‘ recipe by Chef Rossham Rusli, featured on Kuali. To find out the proportions of each ingredient in the recipe, we converted everything into grams (using this converter) and compared those to the total weight of all the ingredients, as a percentage.

For clarity, we disregarded the negligible weights of variable ingredients (whose amount used is up to the person cooking), like sugar and salt to taste, oil for frying anchovies and lubricating the rice, and water for boiling the rice.

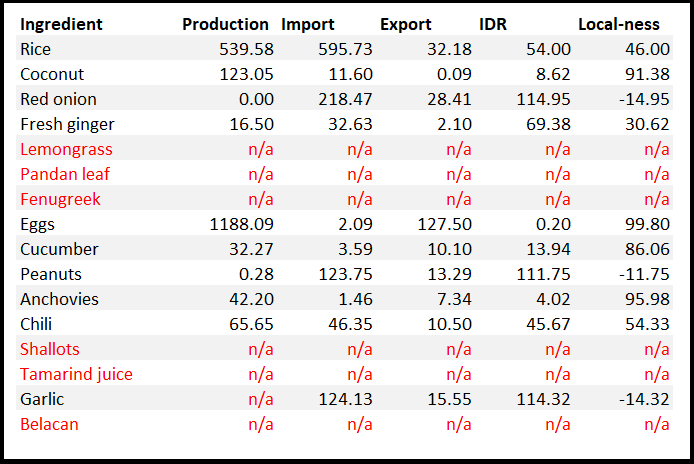

Step 2: Determining how much of each ingredient is imported

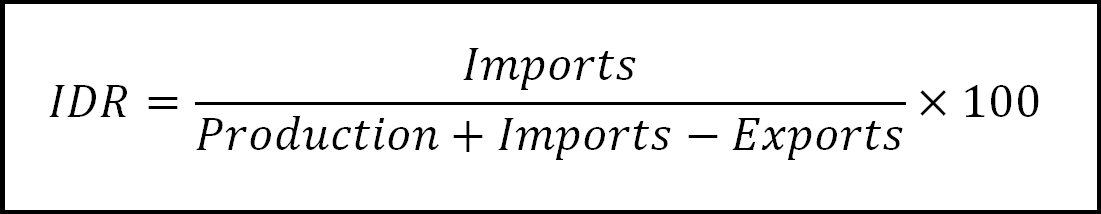

To calculate to what extent each ingredient may be imported, we’ll be using something called the Import Dependency Ratio (IDR). Put simply, this ratio more or less tells us how much of a certain commodity is imported in percentage points, and the remainder is the local supply.

For example, if the IDR of, say, carrots is 60.0, then 60% of the carrots in the Malaysian market is imported, and 40% is sourced locally. To calculate the IDR of a commodity, this formula is used:

It should be noted, however, that this formula can only be used if we import stuff for domestic use and not re-export them at all, so some of the numbers may be a bit off for certain re-exported commodities.

For the production, import and export data, we referred mostly to Tridge for 2015 values, but data may also come from other sources, like the Fisheries Development Authority (LKIM) for anchovy production figures, and the Ministry of Agriculture for ginger, for example.

Still, the data for several ingredients like lemongrass, pandan, fenugreek and belacan eludes us, so we’re leaving the IDRs of those blank.

Since the remainder of the IDR should be the locally-sourced ingredients, we simply subtracted the IDR from 100% to get the percentage of the ingredient in the market that’s local. Of particular interest is the alliums (onions, garlic and shallots).

It would seem that alliums are not commercially planted in Malaysia, but based on available data we do import and re-export them, leading to the negative local values. Nevertheless, since we didn’t make them anyways, we’re setting their local-ness to zero.

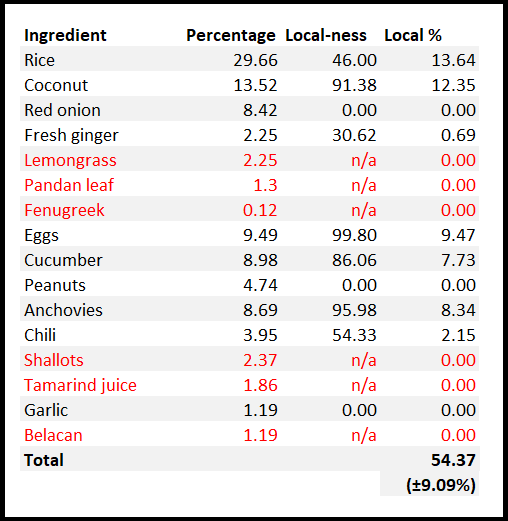

Step 3: Combining the local parts

The final step would be to multiply the local-ness of each ingredient by their portion in the dish.

The missing data accounts for about 9.09% of the dish, so our nasi lemak is somewhere between 54-63% local.

It should be noted that the government have published some IDRs and Self-Sufficiency Levels (SSL) for select ingredients for 2014, but the numbers didn’t vary much from our calculations except for rice. Subbing in the government’s data for rice would make the nasi lemak between 61-70% local.

With the big question answered and out of the way, you might be wondering…

Why should we care how much of our nasi lemak is imported again?

It might be strange to suddenly calculate the imported portion of our nasi lemak out of the blue, but based on that you might have already guessed that we import a whole lot of food every year. The amount had been in the tens of billions: RM51.3 billion in 2017, RM45.4 billion in 2015, and RM38.9 billion in 2013.

Last year alone, we spent RM52 billion to bring in food from the outside. Considering that RM5 billion is more than enough to feed everyone in Perlis lavishly for a year, that’s a lot of imported food.

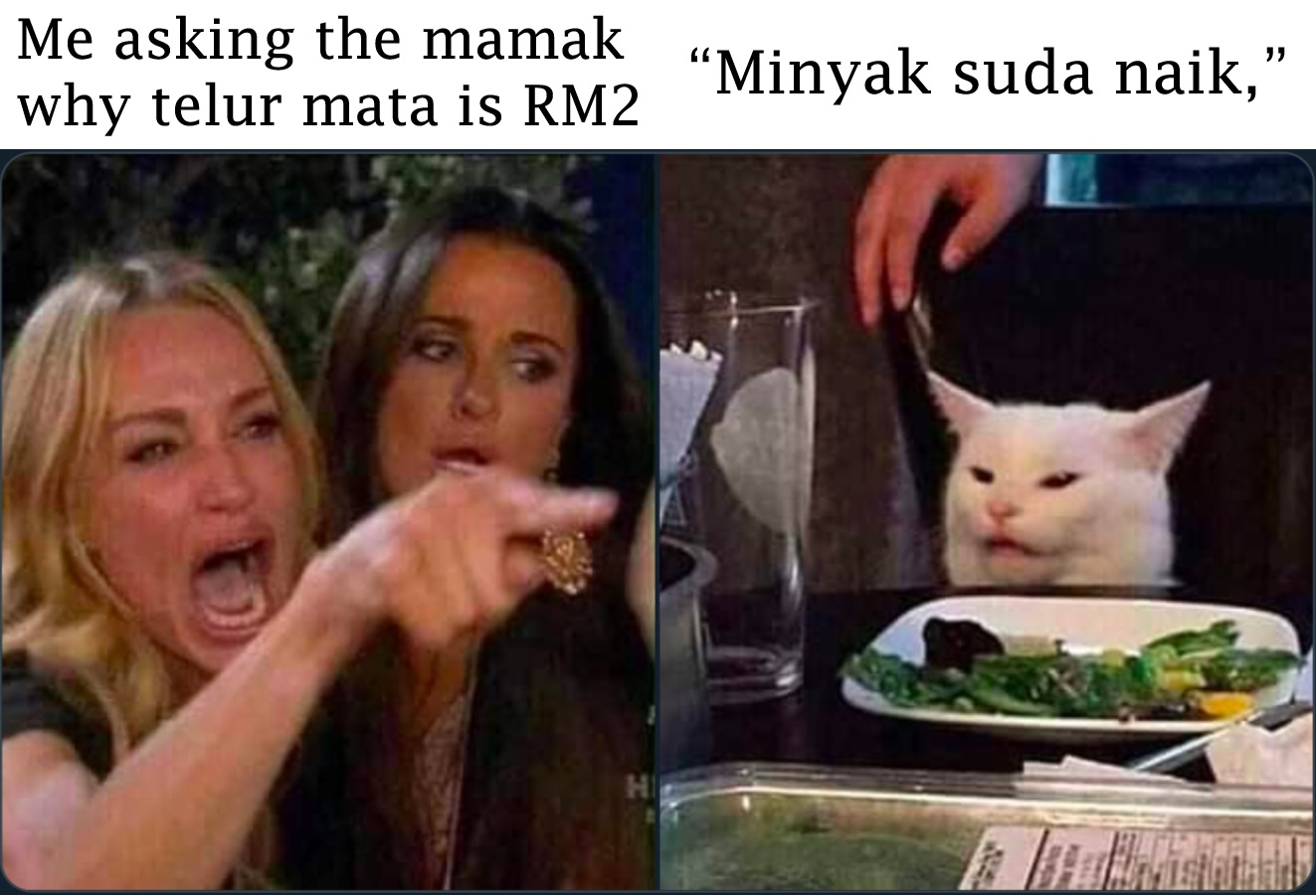

There are several downsides to being dependent on other countries for food, but perhaps the downside closest to the common Malaysian might be food getting more expensive.

Despite a rise in petrol price usually being blamed for expensive teh tarik, our over-reliance on food imports is just as much of a factor. According to Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution, the Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs Minister, this reliance puts us at a disadvantage.

“Our inability to be self-sustaining in terms of food production means that we are at the mercy of importers… This gives power to importers or foreign exporters to increase prices as and when they like and consumers have no choice but to accept it,” – Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution, as reported by The Edge Markets.

An example of this was the onion price surge back in 2017. The Indian government back then set a condition where their exporters cannot trade their onion for less than $850 per tonne until the end on the year, causing the price of onions in Malaysia to be the highest they’ve been within the previous couple of years.

Other countries being able to set the price as they wish is one thing, but when food is bought from outside the country, currency exchange rates come into play as well. Back in 2015, the softening ringgit plus a purported low global production caused shortages and price hikes of spices in Malaysia, with a shopper commenting that the price of clove powder, for one, ballooned up to RM272 per kg from RM20 per kg before.

That was an extreme example, but nevertheless the 10-40% increase in spice prices had affected mamaks and nasi kandar restaurants severely, as more than half of their ingredients are sourced from other countries like Iran, India, Myanmar and Indonesia.

A simple solution to this quandary might be to just make more food on our own. However…

We could have made more food ourselves, but we specialized too much

Like it or not, we can’t make every single type of food that we need. For example, we can’t grow onions commercially (yet) due to soil factors, and it might be impossible for us to make specific kinds of cheese.

However, we are also importing a lot of foods that we should be able to grow locally, like chillies (RM245 million’s worth imported in 2017), bananas (RM38 million), assorted vegetables (RM311 million) and coconuts (RM204 million), to name a few. The coconuts may be because of corruption, but that’s another story for another day.

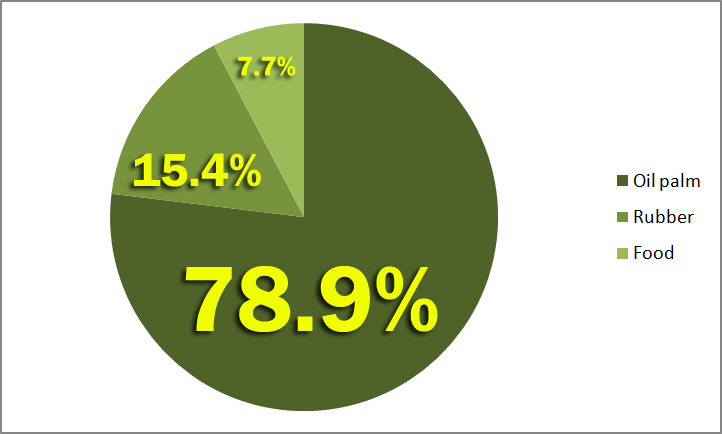

In fact, we only make about 70% of the total food that we need, and the sweet spot according to the government is around 80%. So why aren’t we making enough food? Not enough land is it? Well, we do have a lot of land earmarked for agriculture, about 8,000,000 hectares of it. However, only a tiny fraction of that is used to grow food.

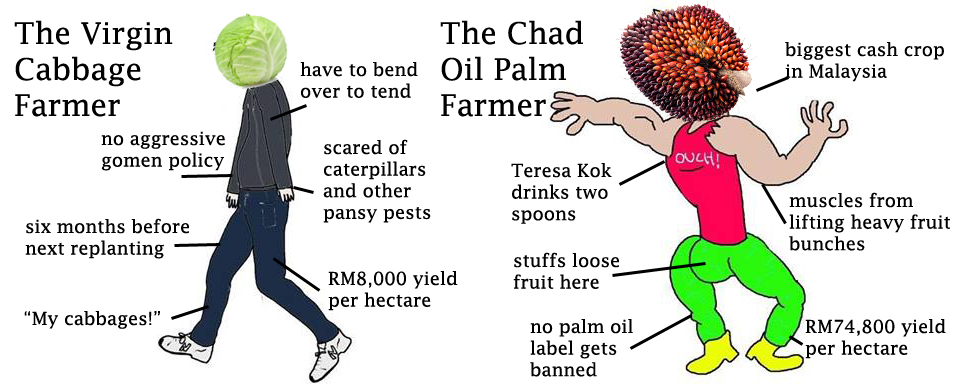

Of the two types of agriculture in Malaysia, plantations have crowded out food production by a lot. You can read a more detailed history of how that happened here, but basically Malaysia’s agricultural policy used to focus on making food, but later that focus shifted on making money and building external trade, hence the gradual shift from food to oil palm.

And it would seem that farmers themselves are gradually shifting to plant oil palm as well.

“Over the last decade, a lot of farmers have started to realise that plantations are a lot easier to maintain than food crops and palm oil prices are relatively stable. So, they quit planting food crops and start planting oil palm. Some of them even sold their agricultural land.

“It is sad to see the padi fields in Kedah being converted into housing and industrial areas.” – Dr Abdul Shukor Juraimi, dean of UPM’s Agriculture Faculty, as quoted by The Edge Markets.

Besides oil palm bringing all the farmers to the yard, it would seem that we might be having less farmers as time goes on as well. As of 2016, out of the 800,000 members of the Farmers Organization Authority, only 15% are less than 40 years old, and about 45% are more than 60 years old.

In simpler terms, many of our farmers are past retirement age, and if nothing is done we’ll seriously be short on farmers, and consequently, food.

Perhaps that is why in recent times Dr Mahathir had advocated for farmers to not only modernize their methods, but also diversify their crops, planting more fruits and vegetables as well. Besides ensuring an alternate source of revenue in case palm oil price drops, it may also help address Malaysia’s food import bill.

He had also recently called on both private and government-owned companies to invest in large-scale food farming instead of just focusing on oil palm. And it probably won’t take much of a shift to change the situation.

“A five to 10 percent change of commodity land into agro-food in stages will make phenomenal changes to the agro-food sector.” – Sim Tze Tzin, Deputy Agriculture Minister, to MalaysiaKini.

As for youths not being interested in agriculture, perhaps the reason for that was that they weren’t properly informed of the opportunities in the sector, and they view farming as a high-risk venture. In more recent times, some, like UPM, have tried to remedy low youth participation by hosting incubator programs that expose its graduates to agricultural entrepreneurship, and the government have came up with detailed plans to ensure our food security and better revenue from agriculture.

We have yet to see results, but if all goes well, maybe one day we can redo the calculations and get a nasi lemak that’s 100% Malaysian.

- 762Shares

- Facebook721

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn8

- Email10

- WhatsApp17