How well is Malaysia handling migrant Covid-19 cases? We compare with other countries.

- 144Shares

- Facebook120

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email5

- WhatsApp7

Since the pandemic began, foreign workers and migrants had taken the spotlight several times, and most of the time it’s nothing to cheer about. The most recent instance is no less worrying. Selangor is currently having a boom in Covid-19 cases, and the Teratai cluster is a huge part of it, with 4,036 positive cases reported as of 24th November. This cluster originated from Top Glove’s worker dormitories in Klang, and of the positive cases so far, 3,846 of them are migrant workers.

Because of the sudden outbreak, the government had ordered Top Glove to close down 28 of its factories to allow the affected workers to get tested and quarantined if necessary. However, some may see this as a smidge too late.

“The virus has spread beyond the factory workers’ circle. We found there are 71 cases or 2.8 per cent stemming from close contacts of the workers, such as their family members. There are workers who are not staying at the worker’s dormitories but at their own houses,” – Tan Sri Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah, Health director-general, in an NST report (23 November).

This incident, plus the government considering to put wristbands on all foreign workers last week to limit their movement in public (regardless of whether they’re a risk or not), may make one wonder… is the government handling Covid-19 cases among migrants well given the circumstances, or just plain badly?

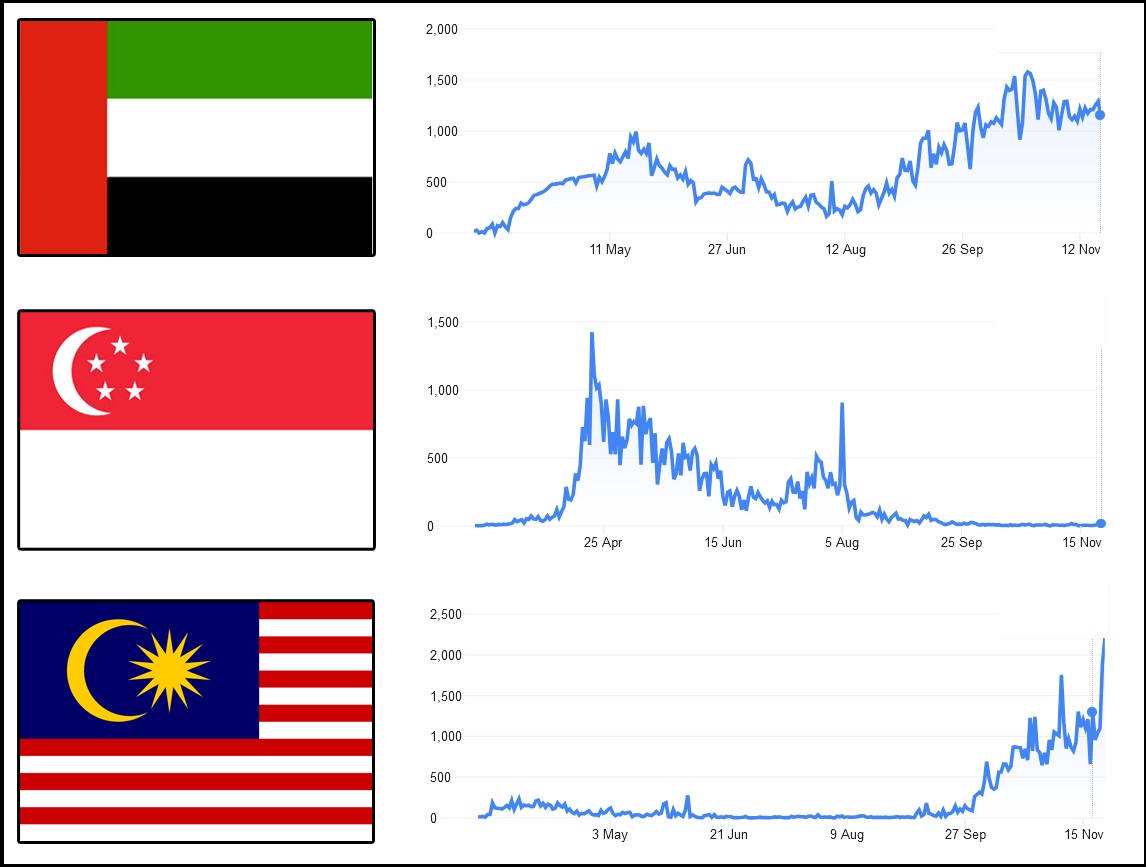

To try and answer that, today we’ll be taking a look at how two other countries, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), are handling their foreign workers amidst this pandemic as a comparison. And the first thing we noticed was…

Cramped living conditions seems to be a common problem in all three countries

We picked Singapore because it’s pretty close to Malaysia, and the UAE because that’s probably the country with the most migrant workers. The UAE belongs to a group of Arab-ish countries called the Gulf States that includes Kuwait and Qatar, and the workforce of these countries are mostly migrant workers. In fact, roughly 90% of the workforce in the UAE are migrants from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Including Malaysia (recently), the bulk of Covid-19 cases in these countries are from migrant workers. While we couldn’t find the exact number of cases in the UAE as well as other Gulf States, it was reported that nearly all Covid-19 cases are of migrant workers living in labor camps.

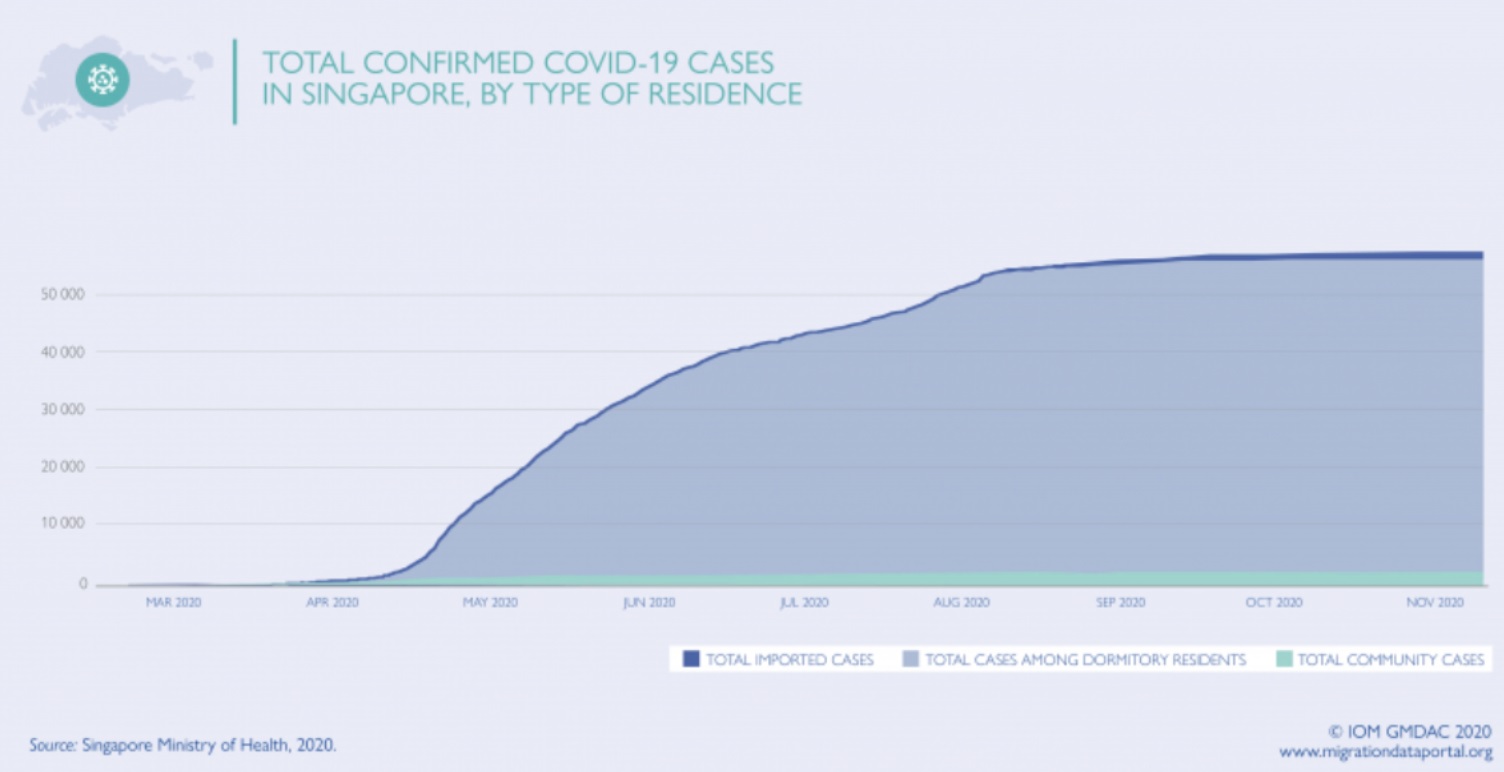

As for Singapore, they divided their number of cases into three:

- community cases,

- import cases, and

- dormitory cases, referring to the dormitories where low-wage migrant workers are housed.

Based on the graph below, we’d say that over 90% of their cases happened in the dormitories.

Based on our readings, in Malaysia and Singapore migrant workers are relatively more in contact with the general population compared to migrant workers in the UAE, where they’re said to live in labor camps.

“I never saw Dubai. I only saw the airport and the camp. You feel like the UAE citizens don’t even know you’re there.” – Gurung, migrant worker in the UAE, in an interview with The Nation.

This might explain why there aren’t that many reports about UAE‘s policies in handling Covid-19 cases among their migrants, compared to Singapore and Malaysia. The other detail we’d like to call attention to is that in all three countries, migrant workers live together in very cramped situations which made social distancing hard. In the UAE, for instance, a report noted that migrant workers generally…

“…live in tightly packed labor camps, often in unsanitary conditions, some without access to running water. These conditions provide the perfect conditions for the spread of Covid-19,” – excerpt of the report, taken from the Guardian.

Singapore’s migrant workers, on the other hand, live in dormitories specially built for the purpose. There seems to be government regulations that specify at least a 4.5 square meters living space for each occupant, but that’s not a lot. In some dormitories, as many as 20 people can be placed in a single room with shared bathrooms, kitchens and common rooms, and the biggest dorm complex can fit up to 24,000 workers at once.

As a side note, while we can find mentions of illegal (or irregular) migrant workers in the UAE and Malaysia, we couldn’t find a reference to them in Singapore in news reports. This may suggest that illegal immigrants aren’t as big as a problem in Singapore today. So now that we have a little background on the three countries…

Here are some of the governments’ efforts in handling Covid-19 among foreign workers

We couldn’t find a convenient dataset for the UAE, but they don’t seem to have significant spikes in their Covid-19 cases. As for Singapore, they had less than 1,000 cases before April, after which migrant workers in the dorms pushed that up. In less than two months, the positive cases jumped to 31,616, of which 92.87% were dormitory cases. Compare the shapes of the three countries’ graphs, and you can see that Malaysia is just beginning to have a problem.

Despite that, we have been aware of Covid-19 cases being a problem among foreign workers from back in August, where it was quoted then that 30% of all our Covid-19 cases are of foreign nationals, mostly foreign workers. So migrant Covid-19 cases aren’t a completely new thing to us. Based on news reports regarding the three countries, here are some of the things the governments have done to handle them.

1. Testing and medical care

The UAE government seems to have set up several testing centers around Dubai back in April, especially in densely populated areas like housing for foreign workers. It was noted then that although the number of positive cases were very small, the contact tracing was a huge task since the workers live close together. In July, this seems to have expanded to mobile Covid-19 testing, with government health officials going into housing blocks and migrant labor camps to administer the swab test.

Service workers were also required to go for screening frequently, and the cost of the tests are free only to some people, like those over 50 or those with other risk factors. Some other Gulf Countries extended free medical care for Covid-19, with Saudi Arabia‘s King Salman reportedly announcing free medical care for the virus for everyone in the country regardless of their legal status.

Starting August, high risk migrant workers in Singapore are required to go through rostered routine testing (RRT). This is mandatory for the workers, except those who have recently been cured from the coronavirus for the next 180 days. Employers are required to schedule their eligible workers for a test once every 14 days. Failure to do that will turn a worker’s status to red in their system, preventing them from working. It seems that the cost of these tests are borne by the government, at least for construction projects, until March next year.

For Malaysia, back in May there was an announcement for all foreign workers to be tested for the coronavirus, and the cost of testing is borne by the employers. That decision seem to be overruled, since a few days later it was stated that only construction workers in red zones would be targeted for testing. With the recent spike in foreign worker cases, the government have again announced that foreign workers from all sectors in KL, Labuan, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Penang, and Sabah will be required to undergo swab tests.

While the testing cost will again be borne by the employers, this time there is a subsidy of up to RM60 for workers with Socso. It should be noted, however, that it seems the SOPs for the implementation haven’t been fully ironed out yet, and some have pointed out that the test required by the government is not that effective in detecting the virus (antigen/swab test, as opposed to polymerase chain reaction), and that the tests aren’t actually covered by Socso. The announcement is pretty recent, so we’ll probably be seeing more changes to the policy soon.

2. Addressing the housing problem

Not much was mentioned about the UAE’s governments efforts in re-housing foreign workers there. It was mentioned that the UAE ordered employers of migrant workers to continue providing housing and food to them even if they got laid off, but most employers reportedly did not heed this. So not only did they not get more spacious dwellings, it would seem that most migrant workers risk losing a place to stay altogether.

Some Gulf Countries have reportedly tried to relocate a portion of their migrant workers into empty buildings to address the overcrowding, but according to one report, ‘many of the efforts to “contain” the virus amounted to simple abandonment.‘ The Saudi Center for Disease Prevention and Control did issue some new guidelines to prohibit overcrowding in migrant housing back in April, but that seems to be about it.

When the outbreak among foreign workers happened in Singapore, their government reportedly sealed off the dormitories and relocated about 10,000 healthy essential workers to other places, with the rest kept locked up in the dorms. Mass testing was carried out on those left behind, and positive cases were gradually isolated, removed from the dorms, and treated.

They have since pledged to improve the condition of the dorms. It was planned that by the end of 2020, each dorm resident will be given at least 6 square meters of living space (up from 4.5 we mentioned earlier), and for the maximum number of beds in each room to be reduced to 10, with at least a 1 meter space between them.

As for Malaysia, we probably don’t need to talk about the snafu regarding the immigration raids and the resulting infection in the crowded detention centers. Rather, we’ll be talking about the law that came into force in September: amendments to the Workers Minimum Standards of Housing and Amenities Act (Act 446). The law will legally require some employers of foreign workers to provide a minimum living space, conduct cleanliness and disinfection exercises in common areas, and provide facilities for the workers to wash and disinfect their hands, among others.

While the amendments had been passed and gazetted since last year, the implementation kept getting postponed to give employers time to comply. Under the Act, employers will need to go through inspection to get a certificate of accommodation, failing which they could be fined up to RM50,000. From September to November, it was reported that 2,668 applications had been made. However, it should be noted that this law only applies to employers who choose to provide accommodations to their workers, and only in Peninsular Malaysia and Labuan.

3. Miscellaneous efforts

There are plenty more to be said, but this article is getting too long already, so we’ll just summarize some points here. On the matter of controlling the movement of foreign workers, the UAE didn’t seem to have anything planned for that, which is may have something to do with their highest risk foreign workers living separately in labor camps. Singapore recently implemented a system where foreign workers in dorms can visit rec centers on a staggered schedule, three hours or so at a time, with the schedule being organized by the SGWorkPass mobile app. They also implemented staggered rest days.

For Malaysia, the wristband for foreign workers still remain a suggestion for now, but it was reported that the Human Resources Ministry had been directed to come up with a plan to ‘restrict foreign worker movement and reduce the risk of community transmissions‘. What the plan is exactly haven’t been revealed yet.

While it may not seem like a Covid-related move, repatriations have also been reported in all three countries, although the motives for each country may be different. In the Gulf States, large number of workers had been sent back to their home countries. This move was implied to have something to do with the reaction of their citizens towards the rate of infection among migrants. The repatriations seem to be met with little enthusiasm by the home countries, due to worries of imported Covid-19 cases. However, to keep their diplomatic relations with the Gulf States intact, not much protest was raised.

Singapore‘s pool of foreign labor had shrunk by about 5% within the first six months of this year, said to be largely due to repatriations. However, there are no direct links to Covid-19 within the report. For Malaysia, there are plans for undocumented workers to either apply to be legalized and keep working in the country, or voluntarily be sent back to their home countries. This plan seems to come into force on 16 Nov, but details about the plan, such as how long the legalized workers can stay or whether they need to pay a fee to return home, were reportedly not revealed yet.

Now that we’ve more or less sped through how each country handled foreign workers during the pandemic, you might be wondering…

So… is Malaysia’s handling of foreign workers good or bad?

Well, the answer to this will be really unsatisfying, but sometimes… it really depends on how you see the issue. For example, we guess we can all agree that the way Singapore handled their dormitory outbreaks seems pretty efficient, with their isolating and their fancy mobile app for rec center visits and their other fancy app for routine testing. However, some may see it as a bit unfair to the migrants, getting locked up with only three hours to walk about a week, while local residents aren’t put through the same restrictions.

Even the recent suggestion about the wristbands for foreign workers in Malaysia have different schools of thought: some see it as dehumanizing migrant workers, while others see it as helpful in terms of disease monitoring and surveillance in the field. Basically, you can argue about any move by the government with regard to foreign workers, and if you’re creative enough you can find a way to twist anything into good or bad.

But that’s just opinion. Speaking objectively, though, it can’t be denied that cases among foreign workers are on the rise. This is despite us knowing about the risk of transmission among foreign workers for a while already, and having seen it happen literally next door. Also, when you put out a new policy and have stakeholders questioning its feasibility afterwards, it’s not a good sign.

Some efforts, like the plan to allow undocumented workers to choose to either be legalized or sent back home, have so little detail that they seem shady. Tenaganita, a local human rights organization, had cautioned foreign workers from rushing into it until more details are disclosed.

“We still have many unanswered questions about the new legalization (recalibration) program for undocumented migrant workers. Do not rush to pay anyone. Please wait until we have official and verified information,”- Tenaganita, as quoted by BenarNews.

Right now, we can see that steps are being taken to address the Teratai cluster, and based on everything we’ve discussed so far, the government seem to be doing things to address the overcrowding problem in foreign workers’ accommodations, plus other plans in the way. But will these plans come into effect in time before another foreign worker cluster shows up? Even if they did make it in time, will they work? Will the employers and foreign workers cooperate?

Only time will tell. Until then, we’ll be keeping our face masks on and patiently waiting for that Covid-19 vaccine to arrive.

- 144Shares

- Facebook120

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email5

- WhatsApp7