Malaysians are allegedly smuggling something precious to India. Can you guess what it is?

- 1.0KShares

- Facebook917

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn13

- Email19

- WhatsApp58

No, it’s not timber, although we did that legally some time back. This time, it’s something that most people won’t find to be precious at all. Something you shake out of your sandals and trouser cuffs after a day at the beach. We’re talking about sand, and lots of it.

In recent news, India was found to have imported some 55,000 tonnes of sand from Malaysia. The sand, reportedly half as cheap as India’s sand, was also believed to be exported illegally from Malaysia, as the government had not approved any permits to do so.

“As far as I know, on record, we have never issued any (approved permits) to anyone to sell sand to India. There seems to be some hanky-panky by someone here.” – Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, the NRE Minister, as reported by the Straits Times.

India, however, had stated that the Malaysian company who exported the sand to them claimed that they have the legal permission to do so. While Malaysians are still in the dark as to who this exporter is, Indians are pleased to have found a seemingly inexhaustible source of sand, as a consignment of 55,000 tonnes of sand equals a week’s worth of business for Chennai and its surrounding areas.

But why does India want our sand? India’s so big, don’t they have their own sand? They do, but what most Malaysians don’t know about the sand business is that…

There are Indian sand mafias who kill people for sand (we’re not joking)

India is rapidly growing. In recent times, the Indian government had been hard at work drawing in investments to stabilize the economy by building much-needed roads and airports, and consequently create jobs. This development involves the construction of a lot of new buildings, and sand is an important component of concrete. This huge demand for sand gave rise to “Sand mafias“, who illegally mine sand and sell it at obscene prices, sometimes up to 100,000 rupees per lorry load (about RM6,500).

Other than bribing officials and dredging sand from unsuitable places, these sand mafias have a reputation for killing and hurting those who tried to stop them from mining sand. Some were hacked to death, like an activist that reported their activities. A journalist exposing sand-mining activities was burned alive, although the police denied that as the motive. But even the police were not safe from the sand mafias, as there were at least three separate cases of police officers being run over by sand trucks.

But India isn’t the only place where people kill each other for sand. In Kenya, conflicts regarding sand mining often end bloody for both parties. In 2015, an incident in Kasikeu, a Kenyan settlement, saw one dead and 11 wounded in a clash between sand miners and locals. The next year, two sand lorry drivers were burnt to death, while a third one became a human pincushion when the locals fired arrows at him.

“The two drivers were burnt beyond recognition, the fracas started when a group of youth protesting the sell of sand clashed with the other group involved in the trade,” – Andrew Mbogo, local policeman, for The Star (Kenya).

Also last year, two Indonesian farmers, who were also anti-sand-mining activists, were attacked by people allegedly from the local sand industry. As the story goes, they had been threatened after protesting against an illegal sand-mining operation in Lumanjang, Indonesia. Not long after lodging a police report, one of them was attacked at his home by at least a dozen men, who ran him over with a motorcycle and left him for dead on the road. The men then found the other farmer and beat him up, before torturing him at the village hall by electrocution and more beatings. The farmer was finally stabbed to death, and his still-bound body was left on the street.

By now, some of you may be wondering why are these people so extreme and dramatic like a Bollywood movie over sand? While part of the reason is money, the reality is that…

The world is running out of sand

![Stop wasting sand, Black! Img from [XCV //]'s YouTube.](https://cilisos.my/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/hqdefault.jpg)

“The construction-building industry is by far the largest consumer of this finite resource. The traditional building of one average-sized house requires 200 tons of sand; a hospital requires 3,000 tons of sand; each kilometer of highway built requires 30,000 tons of sand… A nuclear plant, a staggering 12 million tons of sand…” – Denis Delestrac, director of Sand Wars, a documentary about dwindling sand.

To put it bluntly, the world is running out of sand. But that doesn’t mean that we’ve dug up the Sahara: due to the difference in the way desert sand is made (wind erosion as opposed to tumbling in water), the grains’ shape doesn’t hold the cement together as well as river or marine sand does. And that’s why the construction of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai used sand imported all the way from Australia, despite it being in the middle of a sandy desert.

Marine sand can be used, but it has to be washed first before making concrete, as the salt in the sand can erode the metal frames of buildings over time. So the main choice here is river sand, which is basically any sand found inland that’s not in a desert. The 40 billion tons quoted earlier is believed to be double the amount of sediment that rivers carry annually. In simpler words, we’re using up sand and gravel twice as fast as the rivers can make them.

Despite its increasing rarity, sand is still pretty cheap. Demand, however, is getting higher by the day, so it’s a pretty lucrative business. An MIT project estimated the world’s 2015’s legal sand trade to be worth as much as USD1.72 billion. An Indian press, however, estimated that the illegal sand trade in that country alone can be as high as USD2.3 billion per year. This lucrativeness was believed to be the origin story of the sand mafias, who use murder, land grabs and extortion to guard their piece of the sand pie.

Malaysia had illegal miners for a while now, and the reason for that is corruption

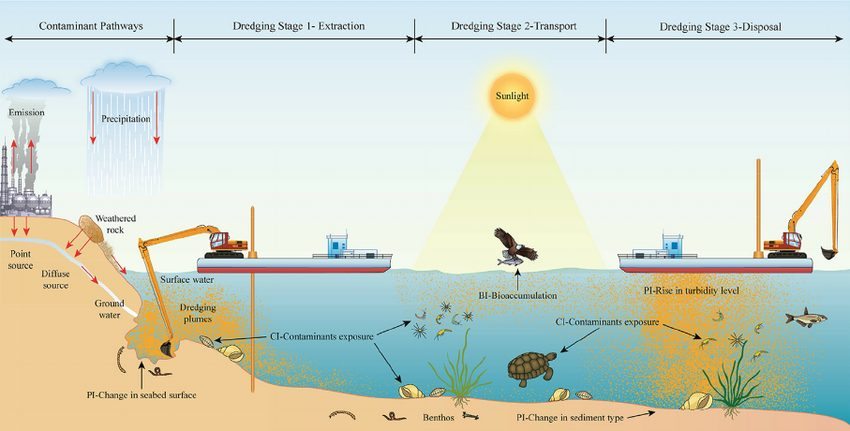

Sand mining, whether legal or illegal, can have a negative impact on the environment. You can read about the negative effects in more detail here, but basically it messes up a river’s flow, dries up groundwater, reduces the quality of water, disrupts the lives of marine animals, brings health problems to people, and causes erosion, which ironically can damage nearby buildings. While the authorities can put some preventive measures in place for legal sand mining activities, that’s not the case with illegal miners. And Malaysia has lots of those.

A quick news search of “illegal sand mining Malaysia” will reveal numerous reports over the years of the activities and arrests of illegal sand miners. For example, back in 2014 the Malay Mail did a series of exposes of illegal sand mining activities in the Klang Valley. What they found was that illegal sites may take out as much as 2,000 tonnes of sand daily, and they discovered four such sites. The President of Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM) in 2013 made a statement to MalaysiaKini that the official production of sand in 2011 was over 37 million tonnes, yet millions more may have been mined and exported through illegal means.

But perhaps the most famous case had ties with Singapore’s land-expansion activities. By dumping huge amounts of sand into the ocean, it was estimated that since 1960, Singapore had grown by about 24 percent. According to data from the UN, Singapore imported 38.6 million tons of sand last year, and half of that comes from Malaysia. The export to Singapore was most probably illegal, too, as Malaysia had banned sand exports to Singapore since 1997.

How could tons of sand cross the border with no one noticing? While the sand mafias in India used a combination of intimidation and violence to have their way, when it comes to illegal sand mining operations in Malaysia, corruption seemed to be the theme. In 2010, 34 government officials were arrested for accepting bribes and sexual favors in return for helping illegal sand get across to Singapore. Bribery was also used to keep the authorities from taking action on illegal mining activities, as the MACC discovered last year.

But corrupt officials are not to blame fully. An interview with some of the illegal sand miners in India revealed that part of the problem lies in the mentality of the illegal miners who think that there’s nothing wrong with mining sand. When asked whether they were worried about the resulting water quality, the answer was a derisive grunt.

“They’re happy with mining… Groundwater depletes: No problem. River is dying: No problem. The miners say, We dig a hole, and the next year the river comes and fills it again. So what’s the problem?” – Vikrant Tongad, a local farmer in Greater Noida, India, for the NY Times.

As it turned out, the shipment to India was actually totes legal yougais. Malaysia had very recently issued sand export permits to India, but the status of the earlier shipment of 55,000 tonnes remained a mystery… until a bit later, when Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi confirmed that there had indeed been two local companies with special permission from the cabinet to export sand to India. The sand, on the other hand, was dredged from the estuaries of Sungai Pahang and Sungai Kelantan.

“If dredging is not done, the shallow estuaries will lead to heavy flooding, like those that happened along Sungai Pahang and Sungai Kelantan previously.” – Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi, NRE Minister, for FMT.

Of course.

Without regulation, mining sand can be catastrophic in the long run

An Indian news site revealed that the import of Malaysian sand was the Indian government’s initiative to address their sand shortage and as a strike at the sand mafia. While our sand may solve India’s problem, one might wonder if it will cause us problems instead. As Anthony Tan Kee Huat, the executive director of the Centre for Environment, Technology and Development Malaysia (Cetdem) had put it a few months ago,

“The report mentioned that the states want to conserve their natural resources. What about conserving our own natural resources?” – Anthony Tan, for FMT.

We may be supplying India with sand now, but are measures being put in place to ensure that we don’t have to do what India’s doing now in the future? SAM, in their statement to MalaysiaKini, had urged both the federal and state government to rethink the laws and procedures regarding issuing sand mining permits, and for the ones enforcing those permits to carry out their duties without fear or favor. That statement was made in 2013, yet recent statistics would suggest that it fell on deaf ears.

While sand mining may be important for progress, it would do well for people involved in it to be aware of the the possible consequences. In 2013, North India was hit with a devastating flood that was deemed as one of the worst tragedies to hit India since a tsunami in 2004, claiming the lives of more than 1,000 people. Sand mining activities in Uttarakhand was believed to be the culprit, causing erosion that frees boulders from a river during heavy rain, which damaged a nearby dam. People have died from bridges collapsing due to erosion. And people whose livings depend on fishing had their incomes disrupted due to sand mining.

But at the end of the day, despite all this, for some people sand is just dirt that can be turned into money. And that’s not surprising at all. People rarely think about sand until it gets in their eyes.

- 1.0KShares

- Facebook917

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn13

- Email19

- WhatsApp58