Holy cow! The gomen’s starting a Bumi quota for importing beef! Here’s why it could be a good thing.

- 1.0KShares

- Facebook940

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn7

- Email22

- WhatsApp43

Soon, 30% of importers getting foreign beef into Malaysia will have to be Bumiputeras, according to the Deputy Minister of the Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry Ministry, Datuk Seri Tajuddin Abdul Rahman. Part of the reason behind that move is to ensure the participation of Bumiputras in the beef import business.

“The 30 per cent quota condition is being fine-tuned and is expected to be implemented as the export approval granted to the existing seven or eight beef exporters are nearing their expiry date and due for renewal soon. In principle, the requirement has been agreed upon and we are only awaiting approval from the abattoirs and the Veterinary Services Department,” – Datuk Seri Tajuddin, as reported by the Borneo Post.

This isn’t the first time a quota is being introduced to solve a problem. While there are quotas set for gender, like the recently announced 30% quota for women in directorial positions in Public-Listed Companies, the prevalent quota systems in Malaysia are set according to race.

We’ll get to the what and whys of racial quotas later, but apart from increasing the Bumi participation rate in meat import, the beef import quota was said to solve another problem, which is… the notorious beef import cartel.

Malaysia, as it turns out, have a beef cartel

Nah. It’s not that notorious la. Most people, upon hearing the word ‘cartel‘, might say “Oh right! Like drug cartels,” or, less commonly, “Oh right! Like the recording company that produced Despacito!”. Cartels might sound badass, but in the economical context, cartels are basically a bunch of people or companies that get together and control the price of their services or products, to make more profit for themselves. Cartels do this by either fixing prices, limiting supply to raise prices, or other restrictive practices.

Say that there are only three grandmas that can make durian cakes, and only they can make that particular cake in Malaysia. If they get together and copyright that cake, then agree to each only make one cake a day so that they can sell each at an agreed high price of RM1,000 a cake, then we’ll have a grandma durian cake cartel.

An example of a big cartel is the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), a group of 14 oil-producing countries that ensure the stability of the oil market by coordinating and unifying the policies of its member countries. While the OPEC is untouchable (even protected by US laws), cartels in general are bad for consumers as they can cause higher prices and restricted supplies. The beef cartel in Malaysia is no exception.

While there are no detailed records of them, beef cartels have been mentioned in several local studies as the reason why imported beef is so expensive. Recent statements from Datuk Seri Tajuddin suggested that beef cartels are also the reason why only 10% of bumiputras are in the beef import business. Although he admitted that it may also be due to the exporters from India being comfortable with their current arrangements with non-bumiputra importers, he had also stated that

“I think it is not fair to deprive bumiputra importers a fair share of the business,” – Datuk Seri Tajuddin, as reported by the Star.

Malaysia’s not the only country in the region suffering from the effects of a beef cartel, either. Indonesians seem to have it worse, as they have to pay almost double what Malaysians and Singaporeans are paying for a kilogram of good beef (Rp. 110,000, or about RM34), even though they consume only 2.61 kgs per person every year. In comparison, Malaysians consume around 6 kgs per person and Singaporeans 15 kgs.

However, it should be known that cartels have recently became illegal in Malaysia. In 2011, the Malaysian Competition Commission (MyCC) was established to enforce the Competition Act 2010 (CA 2010). Its Section 4 prohibits horizontal and vertical agreements between enterprises that lead to cartel-like behavior, such as limiting or controlling production and fixing purchase or selling prices.

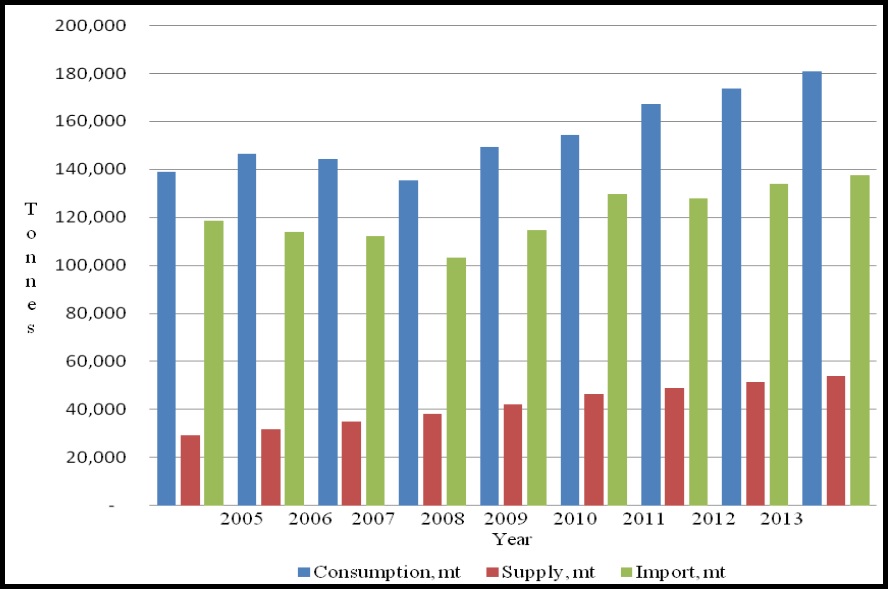

The MyCC may carry out investigations on its own initiative or following a complaint, and the complaint can even be done online by clicking this link. Nevertheless, in recent years, Malaysians are eating more beef, but we’re not producing nearly enough to support that. To keep up with Malaysia’s beef consumption needs, last year Malaysia had to import 82% of its beef. Which brings us to the question…

Can’t we make enough beef ourselves?

In terms of protein production, we can pretty much handle our needs for eggs, poultry and pork ever since the mid 1990s. However, ruminants (animals that can digest grass) like cows, goats and buffaloes are a little trickier. About 90% of the ruminants in Malaysia are produced by small farm holders, and these small farmers do not have formal pastures or facilities for their cows to graze on. This is quite a problem, as they would have spend money to buy feed for their cattle, and that can cost between 5.4 to 19.3% of the total production cost for cows.

The government had, in some areas, allocated official grazing reserves for farmers to raise their ruminants on, but natural grasslands in Malaysia generally don’t grow enough grass, which results in less cows being fed. Due to the relatively high cost of rearing cattle, many farmers had turned to other, more profitable uses of their land, like cultivating palm oil or raising chickens instead.

Currently, Malaysia consumes about 200,000 tonnes of beef every year, but only produces 52,000 tonnes of that amount. Efforts by the government to increase local beef production have worked somewhat, but at the same time we are also consuming more beef, and the local production can’t keep up with our hunger for meat.

Besides problems relating to the cow-rearing, there have been corruption scandals marring efforts to increase Malaysia’s beef production, but we won’t be going into that. For now, the thing to focus on is that we tried to produce more beef to keep up with our needs, and while there were improvements in productions, there’s just not enough local beef to go around. So we probably will have to keep importing beef for a while longer, and pay more for it.

Will introducing Bumi quotas help solve the problem?

The Bumi quota had been a topic of much debate. The New Economic Policy (NEP), an affirmative action introduced in 1971 under the 2nd Malaysia Plan, aimed to eliminate poverty by increasing the wealth of bumiputras, which are the poorest members of the society at that time. Under the policy, bumiputras enjoy several advantages such as a quota for housing at a cheaper price, a portion of shares in companies listing on the stock exchange, preferences in government tenders and financing, places in public universities, and ease of being in the public service, among other things.

Despite Tun Abdul Razak, the Prime Minister at that time announcing that the policy will end in 1990, it stayed in force to this very day. This led to a host of problems, such as skilled Malaysians leaving the country due to ‘social injustice‘ and a subsidy mentality weakening the Bumiputra’s self-resolve to climb without crutches, to name a few.

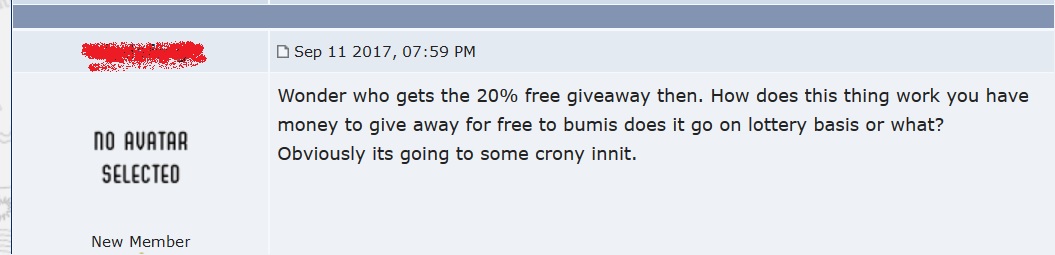

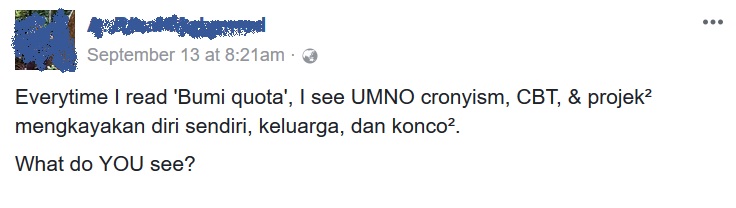

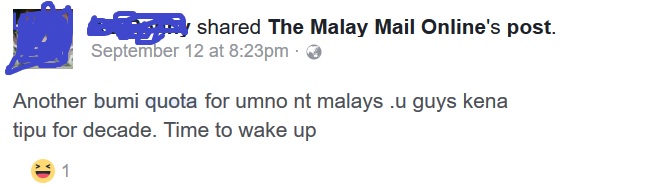

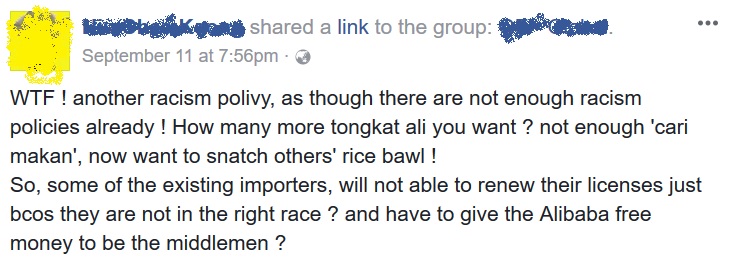

Theoretically speaking, a Bumi quota for importing beef may provide competition to the existing cartels, so it may solve the problem. Practically speaking, however, there’s a whole bunch of ways this can go south. Some people on social media are concerned about who exactly will fill the newly introduced quotas.

Others are concerned that a Bumi quota might be exploited through the Ali Baba method, where a non-Bumi company (the Baba, as in Baba Nyonya) uses a Bumi person as a front to secure contracts (the Ali). The Ali in this relationship does nothing except provide a face, and he or she is paid a certain amount for it.

The Veterinary Services Department is prepared to help establish a Bumiputera consortium, consortium being a group of businesses pooling their resources together to do things. It is believed that the consortium will help in creating more competitive pricing.

“We are rather open on this matter as qualified companies are only required to submit an application to the department to secure a permit to import meat and livestock,” – Datuk Dr Quaza Nizamuddin Hassan Nizam, director-general of the Veterinary Services Department, for Astro Awani.

Other implications of using a racially-based quota system aside, the move should be able to address the two problems it set out to fix in the first place: a lack of Bumiputera beef importers and the monopoly of an imported beef cartel. Care, however, should be taken by the authorities so that the Bumiputera consortium does not evolve into a cartel itself. Otherwise, this whole exercise will be moooot.

- 1.0KShares

- Facebook940

- Twitter9

- LinkedIn7

- Email22

- WhatsApp43