The Japanese spy who secretly saved thousands of Malayans during WWII

- 2.0KShares

- Facebook1.8K

- Twitter19

- LinkedIn21

- Email18

- WhatsApp83

If you enjoyed this story and want more like this, please subscribe to our HARI INI DALAM SEJARAH Facebook group ?

While the atrocities of the Imperial Japanese Army in WWII are well-documented in history, it’s sometimes easy to forget that even the Japanese had a few good apples who were on our side during the most destructive conflict in human history.

If ugaiz watched the movie ‘Schindler’s List’ (based on a true story), yall will remember the character of Oskar Schindler (played by Liam Neeson), the ex-Nazi spy who risked his neck to save around 1,200 Jews from Nazi gas chambers during the Holocaust.

However, there’s a seldom-mentioned story from the Japanese side of the war similar to Schindler’s, about a Japanese man who risked his life to save thousands of locals from Japanese persecution. What’s more, is that it happened right here, in what was then known as British Malaya.

Who was this man, and why was he so loved by the local population that they even allegedly petitioned for his release after Japan’s surrender?

His name was Mamoru Shinozaki

(Disclaimer: Much of this story is taken from Mamoru Shinozaki’s autobiography ‘Syonan: My Story’. In the past, it has been praised as a ‘truthful and unvarnished account’ of the period, but also criticised for ‘self-praise’ and alleged embellishment of his story. We guess if you want take his story with a pinch of MSG?)

Growing up in Japan, lil’ Mamoru was actually expelled from his Kyoto high school for his socialist views. Not the best start to any CV, for sure, but despite this, he still managed to graduate in journalism from Meiji University, eventually becoming a press attaché (a fancy name for ‘diplomatic media person’) for the Japanese govt.

Soon, he would be posted to Berlin, and later to British-ruled Singapore, where our story begins…

In 1940, one year before the Japanese invasion of Malaya

Mamoru was tasked by the Japanese govt to escort some high ranked members of the Imperial Japanese Army to ‘investigate the condition of the coasts’. Totally not shady at all.

But as it turns out, Mamoru and gang were being watched. The very next day, he was summoned by Special Branch (yep, they were around back then too), who arrested him, much to the outrage of the Japanese consul-general:

“It’s war then.” – Japanese consul-general Toyoda, ‘Syonan: My Story’, pg. 18

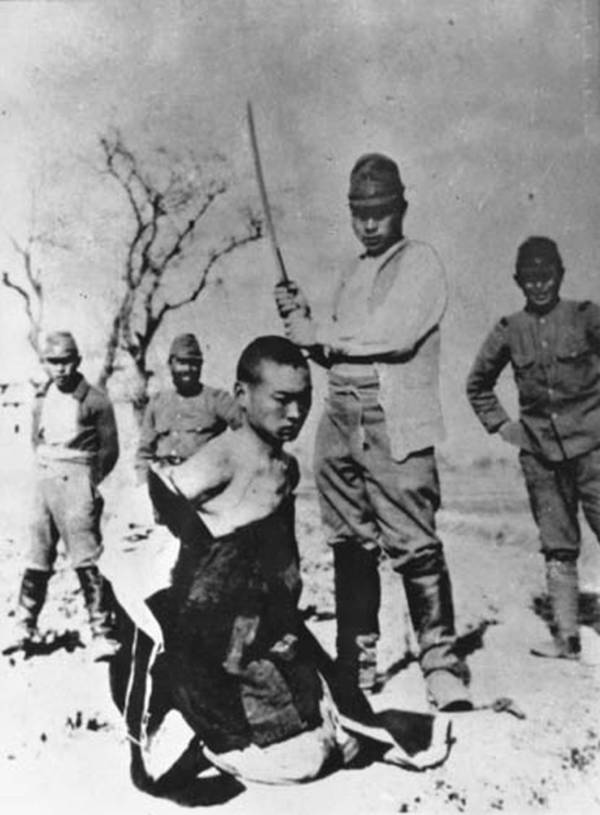

Despite this ominous threat, Mamoru was later charged with espionage for spying on Malaya, and sentenced to three years’ rigorous imprisonment (a fancy term for ‘prison plus hard labour’). He would be sent to Changi Prison to serve out his sentence, where he would be placed among the other foreign prisoners (many of whom were Europeans and Eurasians). The friendships and experiences he had here would later influence his decisions during the Japanese Occupation.

However, he would not get to complete his sentence…

… because, as we all know, the Japanese ‘Mat Basikal™’ would soon ride into Malaya to break up Britain’s tea party in late 1941.

The following year, the Japanese reached Singapore (later renamed by the Japanese as ‘Syonan-to’), forced the Brits to Brexit off Malaya, and eventually freed Mamoru. Not wanting to waste his expertise and familiarity with the local populace, they employed him as Advisor of Defence Headquarters of the new Foreign Affairs Department.

His job? To protect local and foreign Japanese sympathisers by issuing protection passes:

“In battles soldiers have to make quick decisions. They can be arrogant and proud… Not all of them understand military law as applied to civilians. I request your help and (sic) protect good citizens.” – Major-General Kawamura, Japanese commandant of Singapore, ‘Syonan: My Story’, pg. 41

However, having had his own #InsafStory in prison, he wouldn’t just stop at Japanese sympathisers; in fact, he would go out of his way to allegedly print and distribute around 30,000 protection cards to Japanese, British, Chinese, Eurasians, Catholics… heck, pretty much anyone who asked for one got one.

But that’s not all; he also allegedly directly intervened in Kempei Tai (Japanese secret police) arrests whenever he could by flexing his newfound authority to release suspects from a brutal fate. He was also able to do this thanks in part to his connections to the Kempeitai, who had personally rescued him from Changi, and thus respected him for his struggles.

But soon, according to Mamoru, these secret policemen would be transferred and replaced by new guys, who would give him a much harder time. Eventually the Japanese Army would launch Operation Sook-Ching (‘Clean-Up’), which was designed to ‘clean-up’ all anti-Japanese elements in Singapore (including one Lai Teck, about whom we’ve written before). However, the operation quickly devolved into a systematic targeting of local Chinese civilians, as the Japanese were still salty over the Sino-Japanese Wars, and thus hated the Chinese.

In carrying out this operation, the Japanese rounded up thousands of suspected anti-Japanese civilians into concentration camps, and would later execute them by the masses.

According to his own estimates, Mamoru extracted around 2,000 people from these concentration camps. It is unknown exactly how many people died in the Sook Ching Massacre, but Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (who narrowly escaped the massacre) puts the figure around 50,000.

It was around this time that the Japanese Army started to distrust Mamoru

In 1942, Mamoru freed yet another Chinese civilian named Dr. Lim Boon Keng, who was an influential figure among the Chinese community in Singapore. He had been arrested by the Kempeitai due to suspicions of being a Chinese collaborator, having been discovered in possession of a ‘thank-you’ letter from China’s then-leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek himself.

Because of his status within the Chinese community, Mamoru would moot the idea of Dr. Lim heading an Overseas Chinese Association (OCA), which, on its surface, would appear to co-operate with the Japanese, but would have the true objective of protecting the local Chinese community from further oppression:

“I respect Chinese culture–the Chinese are Japan’s old teachers… My name means ‘Cape of China’ (Sino=China, Zaki=Cape)… And my first name is Mamoru, which means ‘to protect’. – Mamoru Shinozaki, ‘Syonan: My Story’, pg. 51

Once the OCA was approved by the Japanese Government, Mamoru, having been elected as its advisor, used it to free many more Chinese on the pretext of adding members to the new association.

However, Mamoru’s constant handouts of get-out-of-jail-free cards started to annoy the Japanese military, and soon, he was relocated (more like ‘fired’) to the education department of the Syonan municipal office. The mayor of Syonan also told him to ‘go back to Japan on holiday’–on a Navy plane, not an Army one, presumably to avoid being banzai’ed by the same soldiers he had pissed off. He took the hint, and did so.

But upon his return to Syonan, he would face yet another problem…

Japan was losing the war

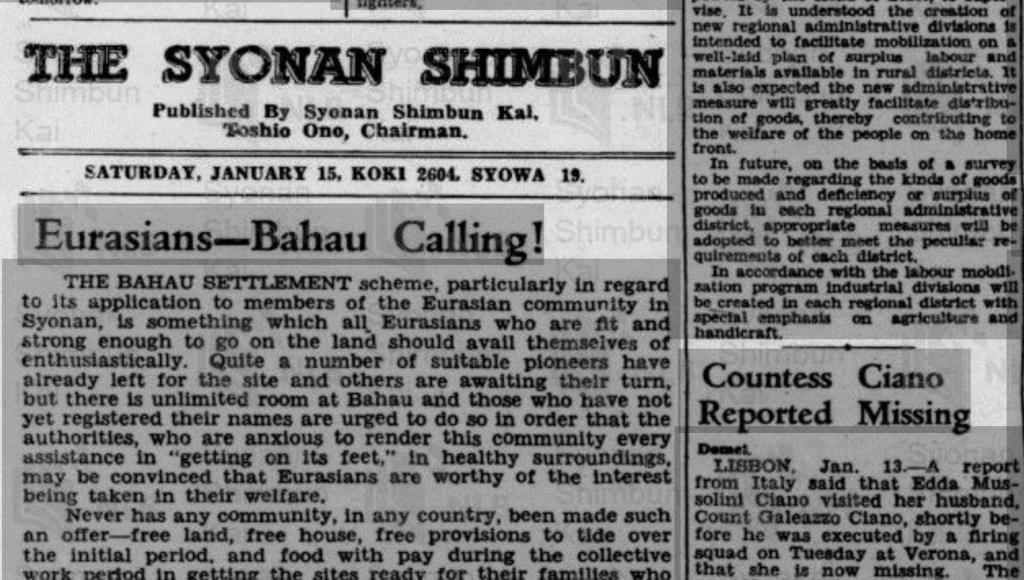

Because of continued Allied victories across the Pacific, Japanese territories started to suffer from a major food shortage. To combat this, the Japanese launched the Grow More Food campaign in Singapore. Mamoru was elected as chief welfare officer and tasked with the evacuation and relocation of hundreds of thousands of Singaporeans to Endau, Johor, and Bahau, Negeri Sembilan to set up farming colonies.

However, these efforts too would soon be hampered by an outbreak of malaria, poor sanitary conditions, and constant attacks from a certain group of Malayan Anti-Japanese Communists.

There wasn’t much that Mamoru could do about the mosquitoes, but he did manage to restore peace for a time by secretly buying off the Communists with rice offerings. Guess it’s hard to get angry on a full stomach, eh?

Anyway, Japan would soon surrender in 1945 after getting ulted by two American atom bombs

Following the Japanese surrender, the Endau and Bahau settlements would be abandoned, and the settlers would return to Singapore.

When the Brits marched back into Singapore, they rounded up around 6,800 Japanese and interned them in a camp in Jurong to await trial for war crimes. Mamoru too was rounded up, but, thanks to his actions, a number of notable folk from the Chinese and Catholic communities stood up for him. He would not only be released, but also became a key witness for the British. (This however remains a contentious claim, as this comes from Mamoru himself, and as mentioned earlier not everyone thinks he was 100% accurate in his story.)

Mamoru, now a key witness for the prosecution, now faced the unenviable task of testifying against the men he had personally worked alongside. Although his testimony managed to save Dr. C.J. Paglar, a Eurasian doctor who had collaborated with the Japanese, he could not similarly save many of his Japanese brethren. Many of the Japanese officers convicted of taking part in Malayan war crimes (especially the Sook Ching Massacre) would later be hanged.

As for Mamoru himself, not much is known about Mamoru’s later life, though he did write a book about his experiences called ‘Syonan: My Story‘. He wouldn’t be the only Japanese Schindler out there tho; Chiune Sugihara is perhaps the more famous Japanese official who used his powers while in Lithuania to help Jews escape Nazi atrocities. Nevertheless, while Mamoru’s story has been disputed in the past, perhaps the lesson to be gained from all this is that even in times of war and destruction, there will always be some who will fight to protect others regardless of nationalitty, creed, and culture.

- 2.0KShares

- Facebook1.8K

- Twitter19

- LinkedIn21

- Email18

- WhatsApp83