Perhilitan just killed more than 2,000 baby turtles. And that might’ve been a good thing.

- 668Shares

- Facebook610

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn7

- Email7

- WhatsApp38

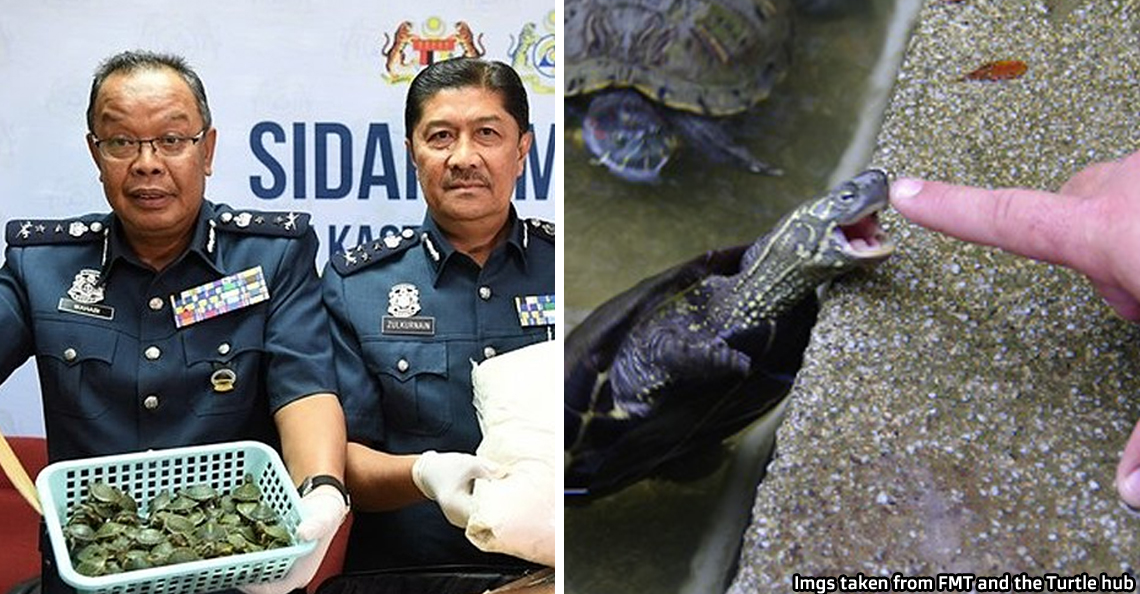

Sometime in June this year, the Perhilitan (Department of Wildlife and National Parks) seized some 2,500 baby turtles from the suitcases of two Indian nationals from China. It was a non-issue at that time, but in August, it was reported that all the turtles have been euthanized.

That raised a minor backlash from a group of wildlife veterinarians, who called the mass killing ‘inhumane’, saying that disposing the 2,000-plus turtles individually would be more respectful. The spokesman for the group had also said that it wouldn’t be hard to take care of those turtles, and he alleged that Perhilitan officers are untrained to take care of animals.

“All that’s needed are several large PVC tanks and running water. I could have purchased those on my own. So I don’t see how an organisation like Perhilitan couldn’t.” – an anonymous vet, to FMT.

Wow. So why didn’t Perhilitan just chuck them all into PVC tanks and running water? Well, we’re not really defending Perhilitan’s way of doing things, but their solution might have been the best one considering the circumstances, as…

These turtles costed Australia more than $800,000 to control

That’s right, the land of baby-eating dingos and conservationist-stabbing stingrays considered these specific kind of turtles a menace, and have spent at least $800,000 of their dollars trying to get rid of them (as of 2016). These turtles are known as red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans), due to their red ‘ears’ and the habit of their wild counterparts of ‘sliding’ into the water when startled. And before we get any further, a PSA:

“Since these sliders live both on land and in water, they’re technically terrapins, but we’re calling them turtles anyway because that’s what the news stories are calling them and ‘turtle’ is the general term for turtles, tortoises and terrapins. Plus you know what we mean. Please don’t ‘um, actually’ us about this.” – writer with comment-reading PTSD.

They look harmless enough at first glance, heck, like a Ninja Turtle, even.

And that’s when the trouble started. Normally, these turtles were only found around three states in the US (Missississippi, Kentucky and Alabama), but their cute mini-selves soon became a popular choice as a cheap pet in the early 1900s. By the 1950s, these turtles have been farmed and shipped outside their native range, and the advent of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in the early 1990s made it even more popular.

But these turtles can live for, like, three decades, which is much longer than a lot of marriages. Also, they can really grow from a cute shell you can carry around in your pocket to the size of a human toddler, or even bigger. Irresponsible pet owners who probably didn’t think this through abandoned their turtles in the wild, where they multiplied and thrived, much to the chagrin of local turtles.

Red-eared sliders can start multiplying as early as two years old, they eat a wide range of food, and they’re known to be aggressive when it comes to competing for nesting sites and places to hang out in the sun. To give an idea of what that’s like for the local wildlife, imagine entering Malaysian Idol or something and making it to the top 20, only to have a red-eared Adele entering the competition out of nowhere and challenging the original contestants into a one-on-one elimination sing-off.

Besides being a huge bummer to local wildlife, red-eared sliders are also known as hosts to salmonella, which is why sales of sliders less than four inches is banned in the US, so that kids won’t put them in their mouths. Improper care of sliders (like, say, cramming a lot of them into small tanks) can also infect them with diseases and parasites, which they will carry with them if and when they’re released/escaped into the wild.

Keeping all that in mind and getting back to the Perhilitan issue, releasing them into the wild is not an option, and China haven’t responded to requests to send them back. Red-eared sliders are categorized as an Invasive Alien Species (IAS) in Malaysia, which are species that are… alien, and invasive. We’ll get more into that later.

“As the red-eared slider is listed as an IAS in Malaysia and the majority of the world, Perhilitan will not release the species into the wild. There is no conservation value for this species because it will damage our ecosystem.” – Abdul Kadir Abu Hassan, Perhilitan’s director-general, as reported by FMT.

While killing them all off may seem drastic, given Perhilitan’s alleged reputation in caring for seized animals, it may arguably be the more humane solution anyways. But if you’re still not convinced of the dangers of this cute turtles…

Malaysia’s had its fair share of invasive species gone wild in the past

We’ve already written articles on some invasive alien species before, like the ikan bandaraya (Pterygoplichtys pardalis) and the Kariba weed (Salvinia molesta), so if you’re a regular reader of Cilisos, you probably have a rough idea of what invasive species are already and how hard it is to get rid of them. Like the red-eared slider, invasive species are any species (that includes plants, animals, fungi and viruses, for example) that has the ability to either really mess up the local ecosystem, disrupt local economy (think crop pests) and/or endanger human health (think the avian influenza).

While we are often exposed to alien species, not all of them can establish themselves, and even less can turn out to be invasive: in Britain, for example, a 1996 study found that only 0.5% of the 220,000 species imported into Britain become naturalized, and not all of them turned out to be invasive. Still, that less than 0.5% of species can have long-lasting consequences. In Malaysia, for example, we’re still dealing with two invasive species that probably came here on trade ships ages ago: crows (Corvus splendens) and rats (Rattus norvegicus).

We won’t go into every single invasive species already in Malaysia (there’s between 106–141 of them) in this article, but we’ll point out some common ones you’ve probably encountered. There’s the African land snail (Achatina fulica), which while any auntie know can be handled with a pinch of salt, is considered one of the worst snail pests for the tropical and sub-tropical region, having caused (or would have caused) great losses in agriculture in several countries.

For Malaysia’s paddy fields, though, another alien snail takes the cake for being so invasive: the golden apple snail (Pomacea calaniculata), commonly known as the siput gondang emas by paddy farmers. These snails were first introduced to the Southeast Asian region as a potential food item sometime in the 1980s, but surprisingly that never caught on. They were first detected in the wild in Malaysia around 1991, and in less than a decade, they became a major menace to paddy fields all over the country. In 2010, costs associated with the snail (losses and eradication costs) reached an estimated RM82 million.

Despite that, they’re still found in the wild today, and you might find their eggs in wet or marshy areas:

As for plants, you might think of rubber and palm oil, but although they are alien, they aren’t really categorized as invasive. You might have heard of acacia trees though: several species of acacia (A. mangium, A. auriculiformis, A. aulacocarpa) had been brought in to the Peninsular Malaysia as early as the 1930s. Due to their ability to grow in nutrient-poor urban soil and their shady crown, they have been used by the government and local councils as shade trees and to reforest burned areas or mines. Despite its popularity in the 70s, acacia trees are now sometimes found growing wild in urban areas and other areas they’re not supposed to.

Another common invasive plant is this:

Known as cogon grass or just ‘lalang‘ (Imperata cylindrica), this plant grows densely in disturbed areas, meaning that if you clear a forest and these plants start growing, new trees will have a hard time regrowing in the same place. This type of lalang is also specially adapted to fire, having fire-resistant rhizomes (like their roots) and highly-flammable leaves. The areas they infest can catch fire and kill off surrounding plants, but they will just regrow, possibly displacing more plants and wildlife (their sharp leaves are unpalatable to wild animals) in the process.

You can read up more on Malaysia’s invasive (and potentially invasive) species in this PDF, but when it comes to handling them…

There’s still plenty to improve, but it seems that we’re getting there

In the case of the turtles, it would seem that Perhilitan’s way of handling it was based on a procedure found in a national plan for IAS, but we couldn’t seem to find it online. But we did found out that a plan for IAS is mentioned in the National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025:

“By 2025, invasive alien species and pathways are identified, priority species controlled and measures are in place to prevent their introduction and establishment.” – Target 11, National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025.

So there is a plan, but it would seem that it’s still in the works. To get there, the key indicators for this plan involve:

- Doubling the public’s awareness (based on 2016 levels) of IAS by 2025,

- Establishing a risk assessment framework for IAS by 2018, and

- Fully implementing the National Action Plan for the Prevention, Eradication, Containment and Control of Invasive Alien Species by 2021.

Besides this seemingly new plan, there are also already measures and provisions in current law to deal with IAS, for example in the Quarantine Act of 1976 and the Plant Quarantine Regulation of 1981. Several government bodies, like the Ministry of Agriculture, the Department of Fisheries, and Perhilitan have been implementing and enforcing regulations regarding the import of certain IAS already, and besides these bodies, the Department of Veterinary Services also have the power to impose the quarantine of animal and birds by certain laws.

There is also something called the Invasive Alien Species Committee/Council for Malaysia, although we can’t find much info about it in the news save for that PDF report we shared earlier. But it’s nice to know that Malaysia is at least aware of the dangers of invasive species, and seems to have a plan in place for it.

But whatever the government does, the best action plan when it comes to IAS is prevention, and it starts with us. We can educate ourselves on what species are invasive, and refrain from importing or buying them. But if you do somehow end up with an invasive species anyways… don’t simply throw them away lah. You can read more on dealing with invasive species through this link and this one.

- 668Shares

- Facebook610

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn7

- Email7

- WhatsApp38