The petty reason M’sian mums can’t pass on their citizenship

- 147Shares

- Facebook112

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn5

- Email4

- WhatsApp22

[UPDATE: 11/03/2025] Hooray for Malaysian mothers with foreign husbands! With the Constitution (Amendment) Bill 2024 passed, your children will now automatically be Malaysians under the Federal Constitution.

As for those who already had children below 18 before the bill was passed, you can now apply for your kid’s citizenship under the same article. [END OF UPDATE]

In the past month, we noticed that a particular issue has been brought into focus again on Twitter.

Some prominent figures have been talking about issues relating to children’s citizenship rights, particularly those who are either stateless or born overseas to Malaysian mothers.

The issue was amplified when news of foreign footballers being granted Malaysian citizenship broke out, leaving many questioning, “how is that possible?”

Tahniah seorang lagi pemain bola sepak dapat kewarganegaraan Malaysia. Wow @IsmailSabri60 bila dan di mana kanak2 yg mohon kewarganegaraan boleh dilatih untuk jadi pemain bola sepak juga?

Satu penghormatan jadi rakyat Malaysia – Sergio Aguero | Astro Awani https://t.co/lnGbnin8a8— Hannah Yeoh (@hannahyeoh) September 17, 2022

Just boils me to the core.

“Making sacrifices” as if thousands of those waiting don’t do the same.

Thousands of kids waiting for their citizenship were denied with no reasons at all, despite being born here, speak the Malay language better than some of us. 🙃 https://t.co/ysxc0mTvHw

— Ainie Haziqah (@AinieHaziqah) August 31, 2022

In case you’re not familiar with the issue, children born to one Malaysian parent and one non-Malaysian parent outside of Malaysia have different fates when it comes to getting a Malaysian citizenship:

- If the Malaysian parent happens to be the father, then his children will get automatic citizenship.

- However, if the Malaysian parent is the mother, her children will have to apply to get citizenship.

And the reason is not some weird security issue, but rather due to a weird technicality…

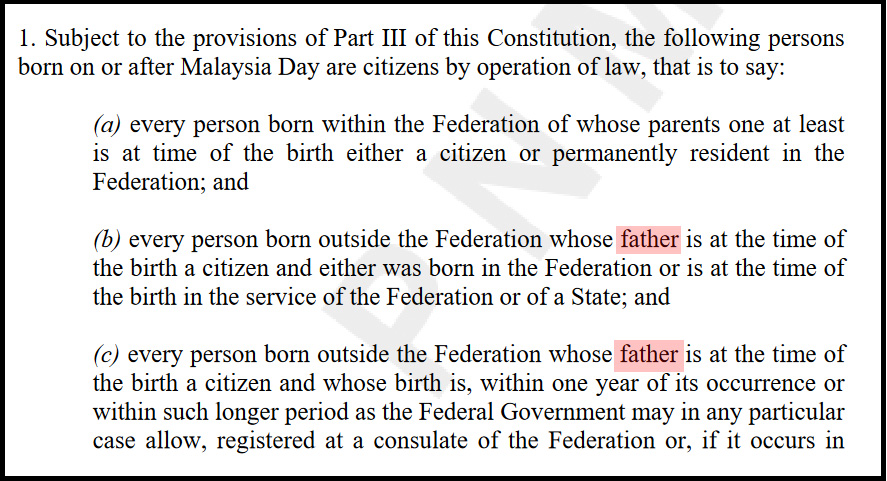

The Federal Constitution said ‘father’ instead of ‘parents’

This technicality is in wording: citizenship stuff for kids born overseas to parents of different nationalities can be found in the Federal Constitution, namely Article 14(1)(b), which states that anyone fulfilling the conditions of its Second Schedule Part II are automatically citizens. The Second Schedule, however, in Sections 1(b) and (c) expressly says ‘father’. Not parent, but specifically a father.

This means that only dads can transfer citizenship automatically. Last year, the High Court tried to change that by ruling that the above sections should be read together with Article 8(2) of the same constitution, which prohibits discrimination by gender, among other things. So ‘father’ should be read as either parent of the child, meaning that anyone born overseas to any Malaysian parent will automatically get citizenship.

Malaysian mothers rejoiced, but not for long. In August 2022, the Court of Appeal reversed that ruling because “it was up to Parliament, not the court, to rewrite the constitution“. While it may seem like a small issue to some…

This technicality may affect Malaysia in the long run

Obviously, this decision to not let children born overseas to Malaysian mothers is devastating to the people involved. For example, their futures are uncertain, and there’s always the possibility of forced separation from their Malaysian family members.

“I’ve always felt a kind of divide between me and my family. My mum and my sister are Malaysians. They can stay here as long as they like. They will be together without thinking that they may be forcibly separated. For me, it’s different.” – *Jennifer, born in Indonesia to a Malaysian mother, as quoted from Al-Jazeera.

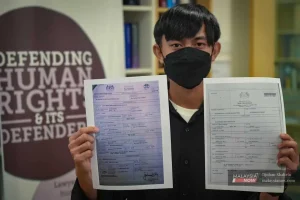

For Malaysia, the effects can be just as bad in the long run: we’re losing out on local talents. For example, there’s the story of Omar Mokhtar Abdul Rahman, who was an excellent student but was stateless due to lack of information about his mother. He was unable to proceed with his scholarship due to his statelessness, and only after his plight was highlighted to the media was he granted citizenship.

Others aren’t so fortunate. Tehmina Kaoosji, who was born in India to a Malaysian mother, grew up not able to access public healthcare and education in Malaysia due to her non-citizenship:

“I was unable to access the Malaysian public healthcare system and public education system. In practical, daily terms, this meant scattered access to primary healthcare appointments, such as vaccinations as a child and also exorbitant foreign student fees for international school education, including annual student visa costs, or losing the right to remain in the country!” – Tehmina during an interview with Malay Mail.

Ironically, she had recently been appointed as one of the participants for International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) 2022 for the Edward R. Murrow Program for Journalists, where she will be representing Malaysia. This despite her still not being identified as a Malaysian by the country.

With the recent concern over brain drain, it’s almost ironic how we’re trying so hard to retain local talents from leaving, but at the same time we’re neglecting potentially talented individuals that we already have in the name of bureaucracy. Perhaps most disheartening of all, this is a big issue that can be solved relatively simply, if there’s the political will for it.

[This article was originally written on 20/09/2022]

- 147Shares

- Facebook112

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn5

- Email4

- WhatsApp22