How leprosy separated a daughter from her biological mother for 50 years

- 368Shares

- Facebook334

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email6

- WhatsApp16

As a child, Mazita Rosli had always suspected that she was different. Although raised by Malay parents, people around her always told her that she looked a bit too Chinese.

And her suspicion peaked when she discovered papers from her parents home. These weren’t ordinary papers; they were her birth certificate and adoption papers.

This discovery planted an idea of finding her biological parents but the scarier thought was that they were located in Pulau Jerejak, which was then known as Malaysian Alcatraz. That’s because it could mean one thing – that her parents might be criminals.

But lil did Mazita know that Pulau Jerejak used to hold a different kind of inmates during the British era – lepers (people who suffer from leprosy). And it all began when her biological mother…

Lim Booi Nya was diagnosed with leprosy at the age of 7

Disclaimer: This story is mainly taken from a book written called A Mother from Pulau Jerejak written by Tan Ean Nee. We have the permission to write this story from Mazita Rosli herself.

Lim Booi Nya was born in Penang to a very huge family. She was the eleventh child out of 17 siblings and she wasn’t always a leper.

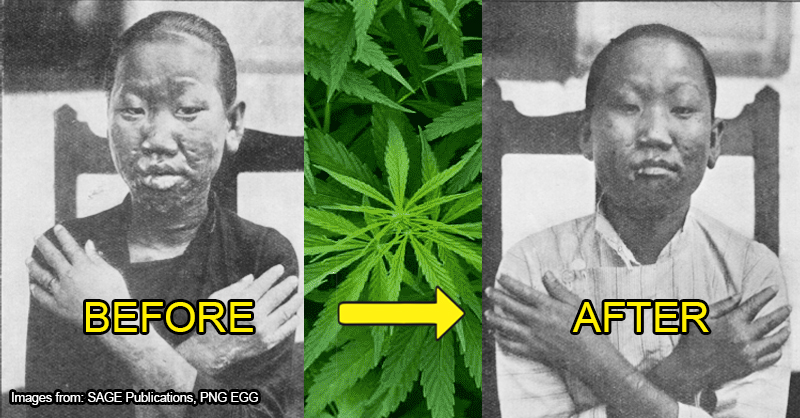

However, she didn’t get to live a normal childhood other children lived because, at the age of 7, she was diagnosed with leprosy, a chronic infectious disease that gives out symptoms that are hard to miss, especially on patient’s skin.

Since then, she was sent to the Pulau Jerejak leprosarium upon the General Hospital’s doctor’s advice. At that time, Pulau Jerejak was known as a centre that housed leprosy patients who had to isolate themselves from the general public.

Mind you, this was a time where the general misconception was that the disease could be spread through touch. We’ve written about this extensively and you can read more here.

But Booi Nya didn’t stay there for long. After three months of staying in the Pulau Jerejak leprosarium, she was transferred to the Sungai Buloh leprosarium for further treatment. Fortunately, it was there that she received her early education as well.

The day Malaya witnessed her independence was also the day Booi Nya was discharged from the leprasorium. She returned home but not for long since she was abused by her mother, who beat and chased after her with a cane. Sometimes, she and her sisters weren’t even given food since her mother favoured her brothers more.

So, she secretly ran back to the Pulau Jerejak leprosy centre at the age of 15. It was around this time that she met her first husband, who fathered five children with her. The eldest was Mazita, who was born as Ong Bee Leng.

But here’s the thing.

Booi Nya was forced to give all her children away

Each time she gave birth to her children, Booi Nya had to give away her children to the welfare centre aka shelter home. In her letter to Mazita, Booi Nya mentioned that she would cry every time she had to give her child away.

Unfortunately, this was a norm back in those days under the Leper Enactment Act. Countries all around the world practiced a segregation policy to either prevent children of leper parents from contracting the disease or, worse, policies to prevent lepers from getting pregnant.

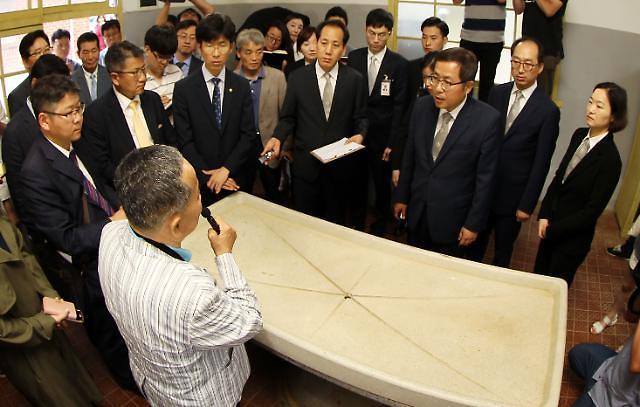

This may be why countries like South Korea used to practice forced abortion on lepers to prevent pregnancies.

Malaysia used to practice the segregation policy where babies of leper couples would be placed in the care of nurses in the centre for six months. They would then be located in shelter homes and would be given up to relatives, friends or adoptive families.

However, there wasn’t any evidence that the child of a leper couple inherited this disease. As a result, though, over 2,000 Malaysian families faced the same fate like Booi Nya and Mazita. You can read about them here, here and here.

And this is also happening globally like in the United States.

“Some 16,000 children were separated from their parents affected by Hansen’s disease and sent to institutions between 1923 and 1986.” – Alice Cruz, UN Special Rapporteur on the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members.

And it didn’t help that lepers in Pulau Jerejak were then transferred to Sungai Buloh in 1969. It was in the same year that the govt actually allowed lepers to return home under the Leprosy Control Programme. But some of them like Booi Nya opted to stay in the Sungai Buloh settlement.

Mazita was only reunited with Booi Nya 50 years later but…

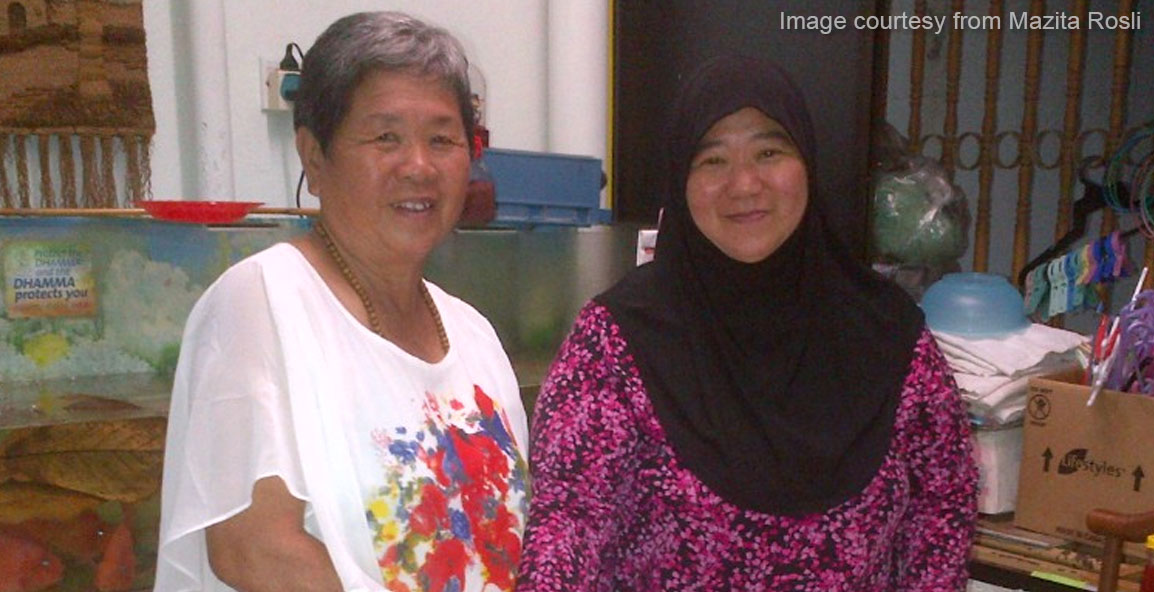

In the past, Booi Nya had tried to find her children but to no avail. It was only after she was approached by Tan Ean Nee, who helps former lepers to find their families through an organisation called Echoes from the Valley of Hope, that she was able to find her eldest daughter, Mazita.

We managed to talk to Ean Nee, who mentioned that reconnecting ex-lepers with their children is not an easy task. In Mazita’s case, she had to scour old records from the Sungai Buloh settlement and the Penang National Registration Department before finding Mazita’s birth certificate.

“It takes years of searching. The longest time that I know of is more than 9 years.” – Ean Nee to CILISOS.

And this tireless effort led to Booi Nya’s reunion with her daughter in October 2013.

Besides, Ean Nee added that govt hospitals could also help families find ex-lepers by writing to the National Registration Department or by conducting DNA tests. The settlement actually had plans to establish a DNA bank for this purpose but nothing was yet to be done.

“It is very important to collect DNA samples from the recovered leprosy patients. They were forcefully separated from their children because of a previous policy but their children may return to look for them in the future.” – The then-director of the settlement, Dato Dr Khalid Ibrahim, as quoted by Echoes from the Valley of Hope.

But here’s the thing – most ex-lepers are not as lucky as Booi Nya for various reasons. Some are still awaiting for their turn to be reunited with their families. And it really doesn’t help that little is known about Pulau Jerejak’s leprosarium.

If you ever visit Pulau Jerejak, chances are you’ll be greeted by this resort…

…which was built on one of the blocks of the leprosarium. Mazita finds this rather disappointing because not acknowledging Pulau Jerejak’s history is part why ex-lepers are finding it hard to find their family members.

“The history of their (lepers) existence must be remembered in the right way so that the stories of their life can be made known to their families and the future generations.” – Mazita, excerpt from Mother from Pulau Jerejak.

Note: You can get Mother from Pulau Jerejak or help the leper community by contacting Echoes from the Valley of Hope here.

- 368Shares

- Facebook334

- Twitter6

- LinkedIn6

- Email6

- WhatsApp16