This book tells us what Malaysians were like 50 years ago

- 3.4KShares

- Facebook3.3K

- Twitter18

- LinkedIn18

- Email20

- WhatsApp68

One of our readers, Kevin Bathman, highlighted a really cool book to us, titled ‘Malaysians’. The book is a collection of paintings by Mohamed Hoessein Enas, one of the earliest generations of local artists. Commissioned by Shell, the book was published in 1963, the year our nation was formed. It even has a foreword by our first Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, written on 11 September, 5 days before the formation!

Kevin’s copy belonged to his father, who started working for the gas company in 1972 and retired in 2002. He believes it’s out of publication already, which is why this book is super precious. ‘Malaysians’ has 51 of Hoessein’s paintings of people and scenes that show our melting pot of cultures, a fascinating portrait of what Malaysia (and Malaysians) was like 50 years ago. With it he adds his own commentary and observations. But more importantly, the artist painted some things and practices that are no longer around today! Such as

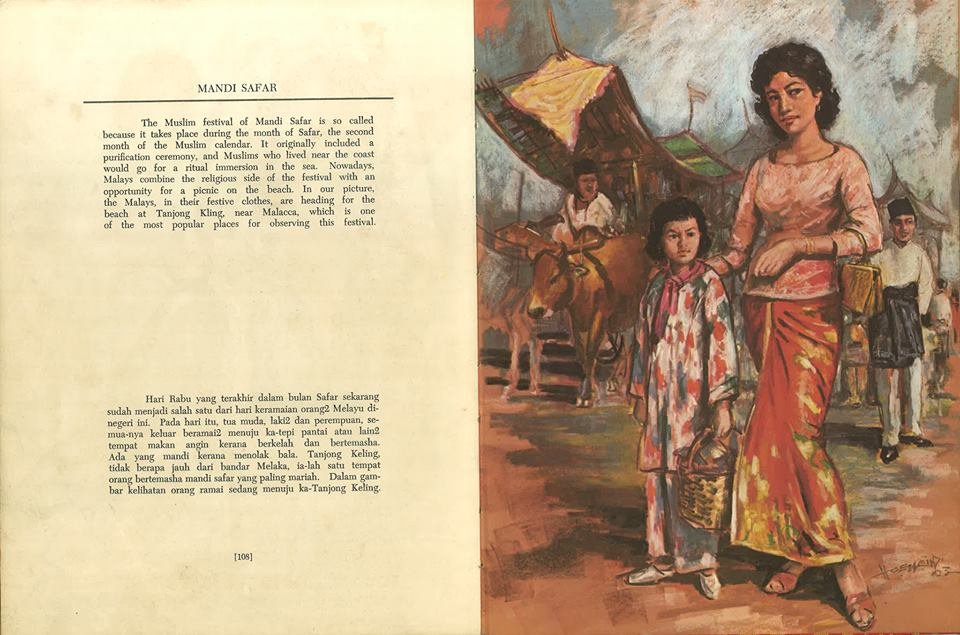

Mandi Safar…a tradition that Muslims don’t do any more coz it’s got Hindu elements

Mandi Safar was a festival practiced by Muslims in the past, particularly people in Malacca, Kelantan, Terengganu, Negeri Sembilan, Sabah and Sarawak. It took place on the last Wednesday of the month of Safar, which is the second month of the Muslim calendar. Crowds would gather at beaches and take a dip in the sea as part of the ritual, or they would drink water they’ve soaked a paper or small board with scripture from the Quran in. This water is known as air safar.

The ritual is no longer in practice by Muslims today because that same year (in 1963), Berita Harian reported the Deputy M ufti of Johor, Dato Dr. Abd. Jalil Hassan as stating that those rituals were “heresy and nonsense”. He declared a fatwa against it, so from then on, Islam rejected it as a pagan practice.

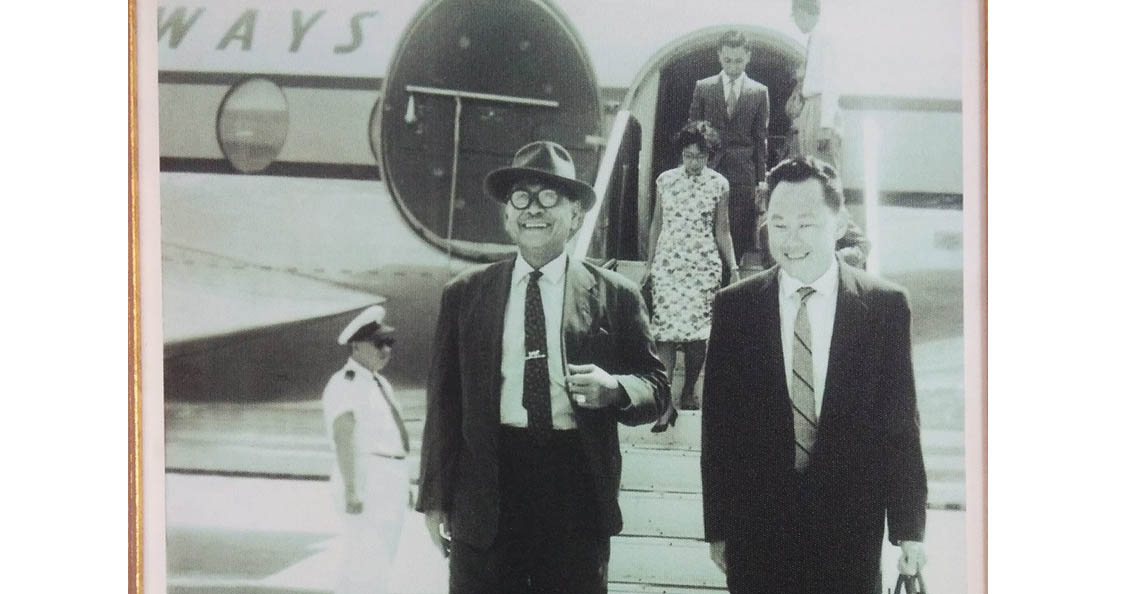

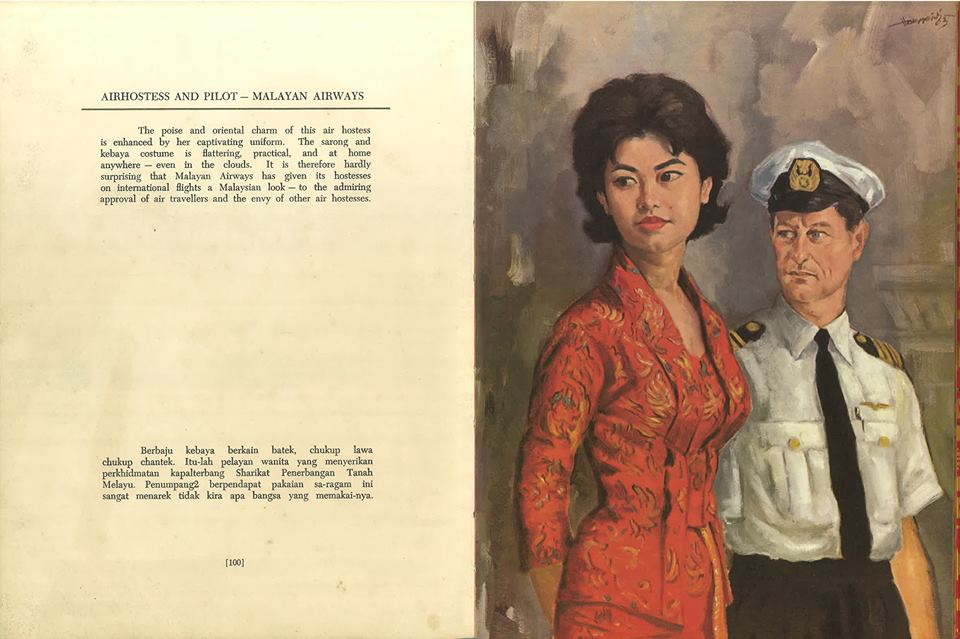

MAS has had a rich history. Thanks to an initiative by some British company in Liverpool, it resulted in the establishment of Malayan Airways Limited (abbreviated MAL) on 12 Oc 1937. But it was 10 years later that they welcomed their first paying passengers, on 1 May 1947.

Hoessein painted the above portrait of a Malayan Airways air hostess in the airline’s signature kebaya and sarong uniform, observing that the look is “at home anywhere – even in the clouds”. At the time, the airline had only a few international destinations: Brunei, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand and South Vietnam. Nevertheless, their hostesses proudly sported the Malaysian look on these flights, “to the admiring approval of air travellers and the envy of other air hostesses”, Hossein notes.

Today, MAS’s female cabin crew are still rockin the kabaya. Company CCO Paul Simmons called the uniform an iconic symbol and a source of pride for generations. MAS may no longer be called Malayan Airways, but some good things never change. 😉

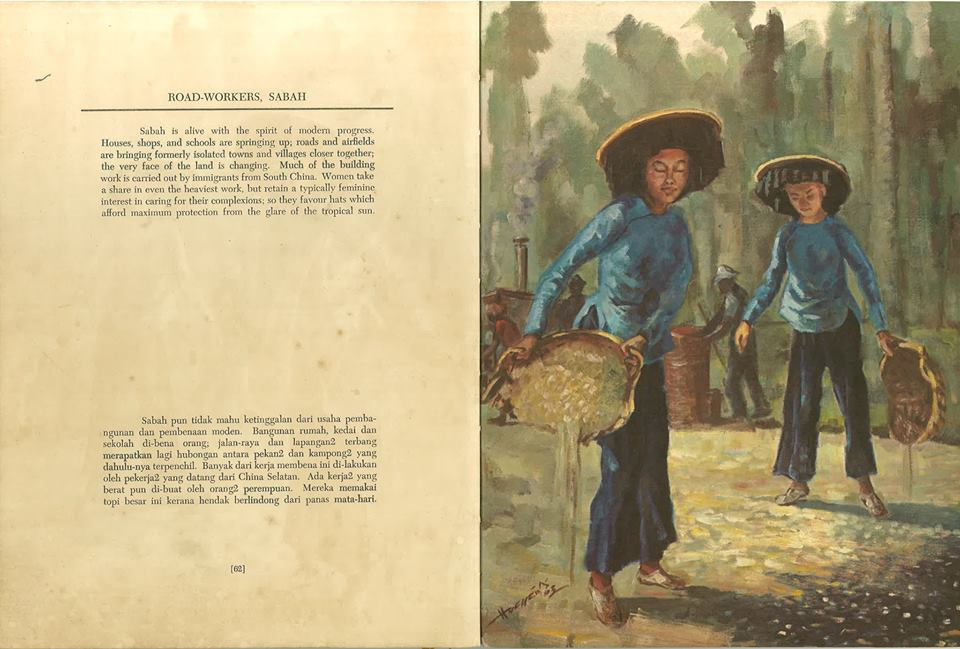

Sabah’s progress was already in swing during the 60s, Hoessein related, as houses, shops, schools, roads and airfields sprung up to connect formerly isolated towns. Much of the building work is carried out by immigrants from South China, so looks like even back then we like to rely on foreign workers. 😆

The women immigrants didn’t shy away from heavy duty work like road construction, but they did try to protect their complexions by wearing hats, coz no SPF those days. 😛 From the painting, it looks like they’re either sifting or laying gravel, commonly used as a road base, down on the area where they’re gonna build the road. While in 2018, female foreign workers are allowed in work in the construction sector, China is not on the list of approved source countries for labour.

If you look at our history, tin spurred the beginning of road-building in Malaya in 1860, with Tengku Menteri Ngah Ibrahim, the Perak Sultan’s administration assistant, lashing together timber with strips of rattan to form rudimentary roads, a feat that happened 25 years before the first railway arrived. They used that to transport tin from Kamunting (near Taiping) to Port Weld. Because of Perak’s abundance of tin, the British developed that state quicker than others (including road-building) for their economic interests.

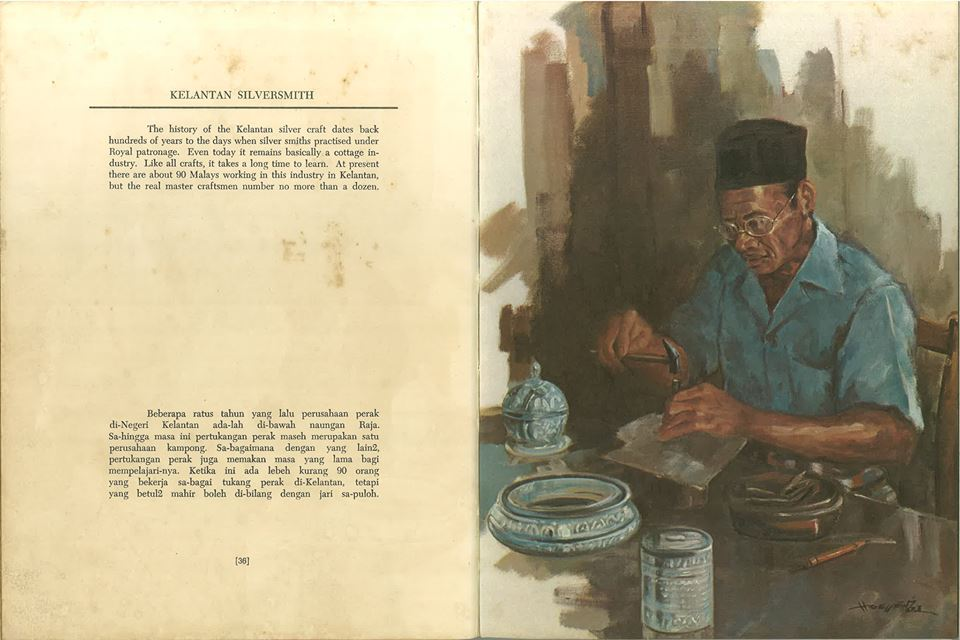

Kelantan’s always been famous for silver craft since ancient times, when royal households commissioned artisans to make keris sheaths, jewellery boxes and dining-ware. Despite the advancement in technology, many customers still prefer traditionally crafted silver, says Pok Li, one of the last traditional silversmiths in the society today. Even in Hoessein’s book, he mentioned there were only 90 such craftsmen left, and that’s 50 years ago.

“When I started to learn the basics, it was difficult. I had to use hammers and chisels, and I took 8 hours to make a ring.” – Pok Li, The Malaysia Times

Today with machines, it only takes around 2 hours to make a ring, said Pok Li, who began his apprenticeship at 15. Not only do Kelantan silversmiths have to contend with machines, they’ve found competitors in…. Penang and Perak! These states have been selling silver items cheaper than Kelantan. When they hit the market after the 90s, the industry in Kelantan plummeted.

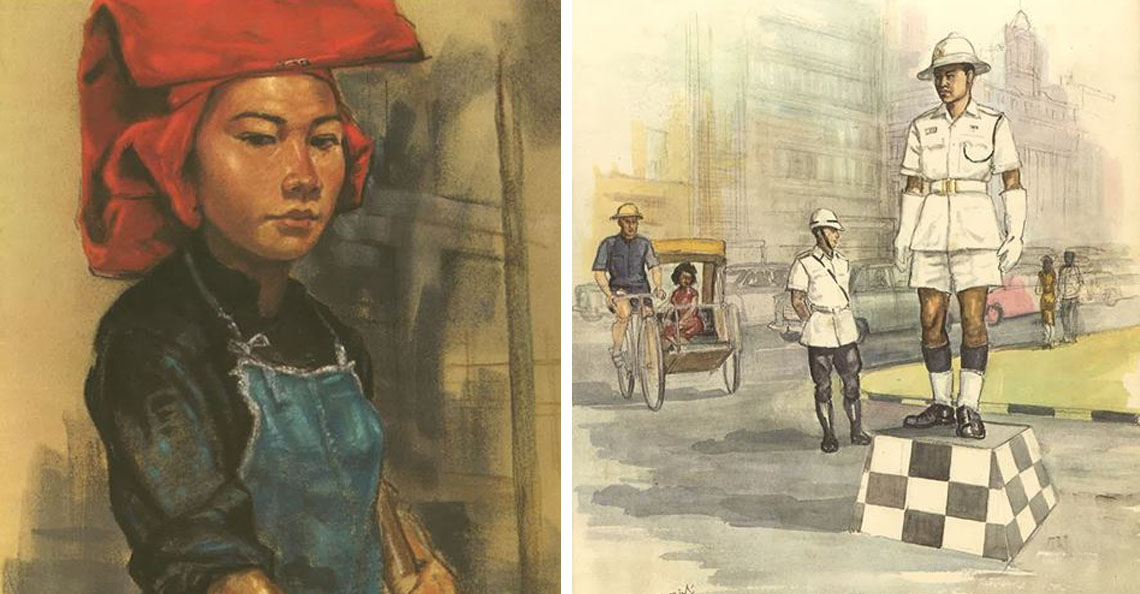

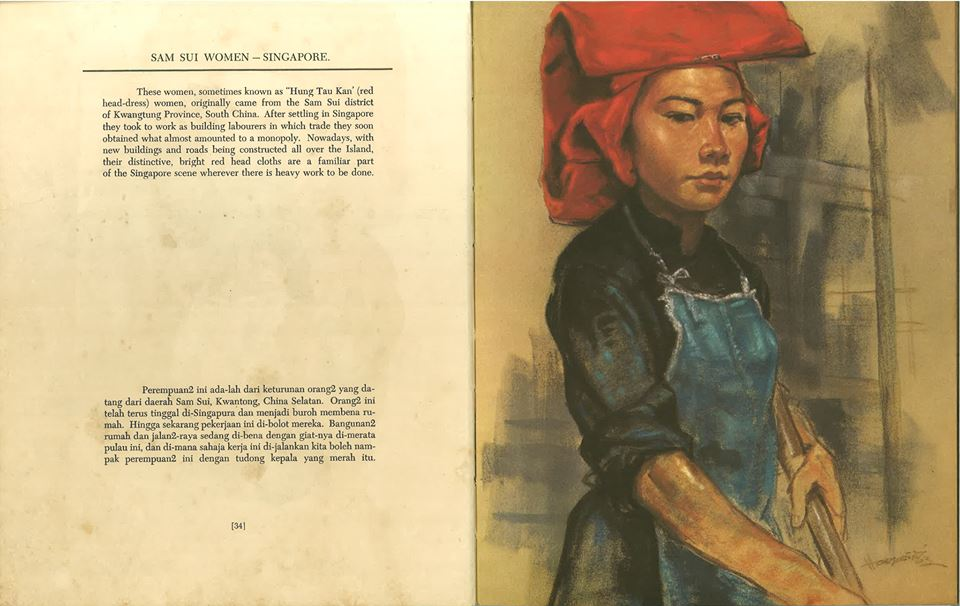

Something we never see anymore are the Sam Sui women of Singapore (when Singapore was part of Malaysia from 1963-65). These women, sometimes known as ‘Hung Tau Kan’ (red headdress) women, came from the Sam Sui district of South China during the 20s-40s and settled here, in search of construction and industrial jobs. With new buildings and roads popping up, their distinctive, bright red head cloths were a familiar scene wherever there is heavy labour, commented Hoessein.

The Sam Sui women, all 2,000 of them who came here, practically monopolised the industry. In fact, we have these ladies to thank for our early development. They lived together in cramped conditions, helping each other out, and formed a very tight bond. Sam Sui women had a reputation of rejecting unsavoury jobs (like drugs, peddling, prostitution and other vices), even that meant living in poverty. A popular TV series called Samsui Women was produced in Singapore in 1986.

As everything became mechanised, there was little need for their services, so eventually they retired. They remained in Singapore, choosing to make it their home. By 2014, it was estimated that there were only 2 Sam Sui women left, both of them lived alone in one-room rental flats.

Some of these practices have died out, but we can preserve them through this book

This entire booklet of beautiful paintings by Hoessein Enas just blows the mind. For the young people, it’s an amazing window into the yesteryear, while for older folk, it’s full of nostalgia. Many of the scenes and practices such as mandi safar and Sam Sui women have phased out, and Malayan Airways is now MAS.

We also noted how the Malay woman in the mandi safar painting did not wear a tudung, as was the norm back then. We’ve written a whole article on this before. Basically tudungs were reserved for special occasions like funerals or kenduris and most Malay women went about comfortably without one. On the other hand, Chinese women don’t wear samfus for everyday wear, like the woman captured in Hoessein’s painting.

But it’s nice to see that some things have not changed… satay sellers by the roadside, night hawkers, cultural performances, and Orang Asli’s traditional dressing, to name a few from the book. What’s also interesting about this book is that it’s no longer in publication and Kevin’s copy may be the last of its kind! For that it deserves a spot in the museum or library.

- 3.4KShares

- Facebook3.3K

- Twitter18

- LinkedIn18

- Email20

- WhatsApp68