5 old school Malaysian snacks with tasty origin stories

- 6.5KShares

- Facebook6.2K

- Twitter28

- LinkedIn20

- Email21

- WhatsApp235

There are some snacks that have been around all our lives that it’s like air – we don’t even question it, it’s just there. From time to time we might munch on an asam and think, “Hmm, sedapnya, but is this asam really a guy’s taik hidung?” (we’ll talk about this more later), have a laugh, but then promptly forget about it.

Well, not anymore. For once, we actually decided to look into the old-school snacks that we grew up with, and see if there are any surprising stories, or answers to forgotten questions we might have had. As we found out, some of them might even have that surprise right on the packaging itself.

For example, let’s start with…

1. PoPo fish muruku’s founder is not Indian

This snack might reveal some false memories that you might have. For example, when you think of the packaging, you might remember that there are some Tamil writings on it. And because it’s muruku, you would automatically assume that it would be an Indian guy who made this.

But if you look at it again closely, the writings on it are in Malay (in rumi and Jawi), English, and Chinese. And that’s because PoPo Fish Snack was actually created by a Chinese person. Yup, go take a look again at the packaging. Shocking, right?

The late Foong Chek Lung started his company Thien Cheong in 1955, where he would sell imported household products from door to door using a bicycle. In the 1970s, he expanded his business into processing anchovies, and that’s when he thought (dramatically imagined by Cilisos), “Hmm…since I’m processing all this fish, why not make my own fish muruku?”

Armed with a frying wok, a rectangular cutter, and his bare hands, he spent sleepless nights experimenting before finally getting that cannot-eat-just-one-packet taste. After he got that, and we assume ate a whole bunch of his own muruku non-stop, he had to think about the packaging, and there’s a pretty touching story behind it.

He decided to use a picture of a baby to remind himself to work hard for his firstborn son and family, and named it popo (or baobao in Mandarin) which meant colloquially as “my baby”. It’s also a short name which is easy for the customers to remember, though we’re pretty sure it’s just called “white packet muruku” by people today.

Btw, does anyone else feel like having muruku now?

2. Mamee used to be an instant noodles company

Have you ever wondered why Mamee looks exactly like instant noodles? That’s because the company that made it first started as exactly that – an instant noodle business, but it was a huge failure.

When Pang Chin Hing started Lucky Noodles in the 1970s, he didn’t know anything about instant noodles. His friend convinced him to do so and claimed it had a brighter future than his job as a second-hand car dealer.

Well, Lucky Noodles wasn’t so lucky as the future was very nearly bankruptcy – they were competing with the big boys Maggi and Cintan, and shops didn’t want to take in another instant noodle brand on their shelves. The son, Tee Chew, dreaded going back after traveling all over Malaysia selling noodles to kedai runcits, only to come back to a scolding from his father for not getting many sales.

But he did notice something during his travels. In the rural areas, farmworkers and especially rubber tappers would eat instant noodles dry – they’d just open the packet and pour the flavour in, and eat it just like that.

That was a hol up moment for him – why not just sell a snack like that?

So that’s how Mamee was born, but they changed their target market to children, as adults would still prefer to eat the more famous brands, which is why it has a more colourful design.

The name was also inspired by his travels. The cheapest food he could find was wantan mee for 30 cents, and he’d ask for double servings in Cantonese saying “ma-mee!”

Interestingly, Mamee has started selling instant noodles again after a long hiatus. Looks like Chin Hing’s friend was right – instant noodles are the future, he just didn’t specify when.

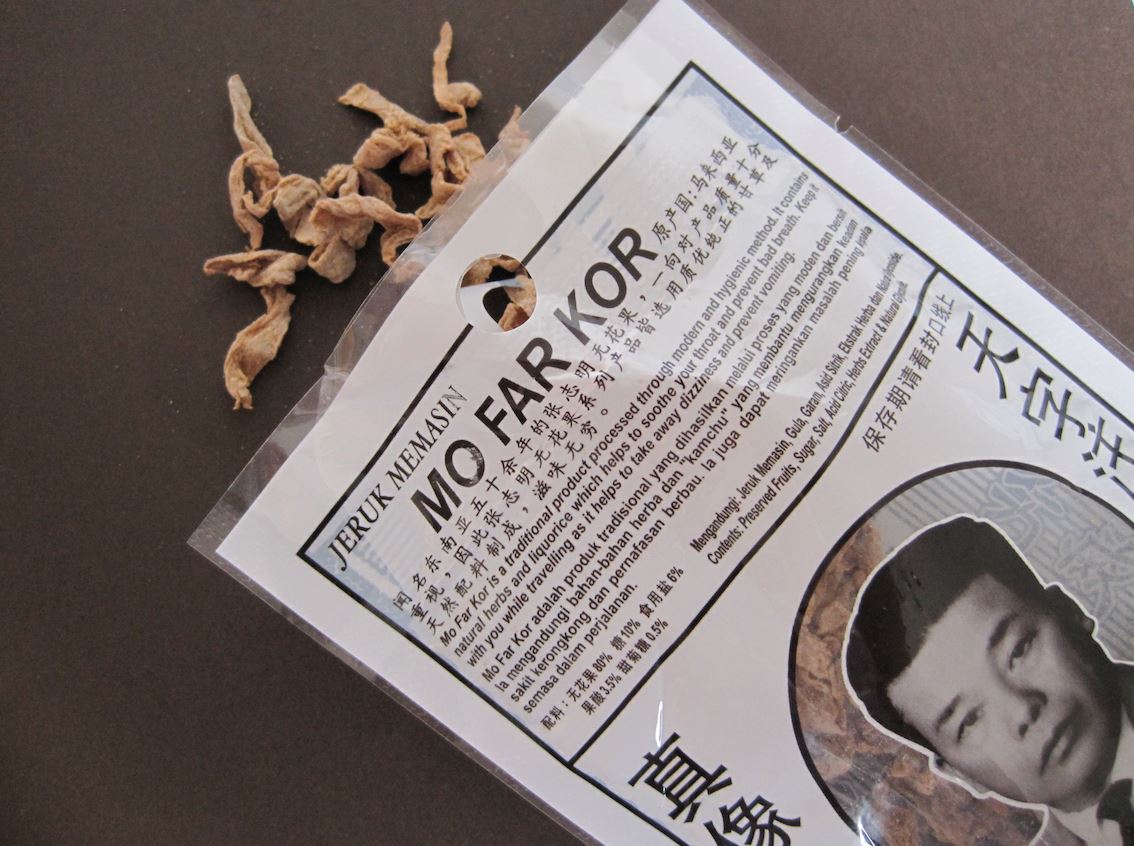

3. Mo fa kor is NOT from Hong Kong and it’s NOT his taik hidung

This dude on the obituary looking packaging is probably the most kena fitnah man in the whole of Malaysia because all school kids will say that this jeruk is his taik hidung (But we all ate it anyway).

We might think that his name is Mo Fa Kor, since it’s his face on the packaging. But his real name is actually Cheong Chee Ming and despite people thinking the product is from Hong Kong, his company was actually started in Menglembu, Perak in 1945. Mo fa kor is the name of the fruit the jeruk is made from, which means “non-flowering fruit” in Cantonese.

While checking online, we found out that quite a lot of people thought it refers to fruits from the calabash tree:

But akshually, mo fa kor is another name for figs, which are these ones here:

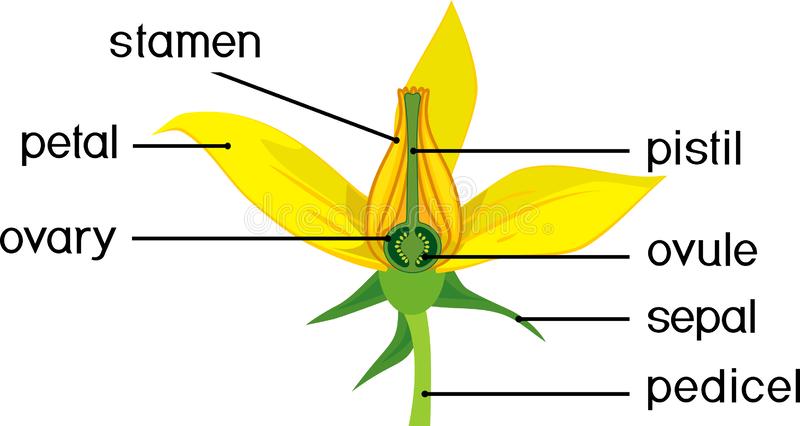

See, the calabash tree actually has flowers – it just blooms at night and then dies the day after. Fig trees, on the other hand, might seem like they don’t have flowers, but the fruit is actually the flower – an inverted flower. When the fruit matures, what’s inside it are the remains of the flowers, and the things that look like seeds are actually undeveloped flower ovaries. But of course, whoever named it didn’t know this back then, which is why it’s called the non-flowering fruit.

This mistake on the fruit is only a Malaysian thing though, cause if you check on our neighbours down south they correctly labeled it as dried figs. Also, case closed: the asam is not uncle Mo Fa Kor’s taik hidung. #JusticeForUncle

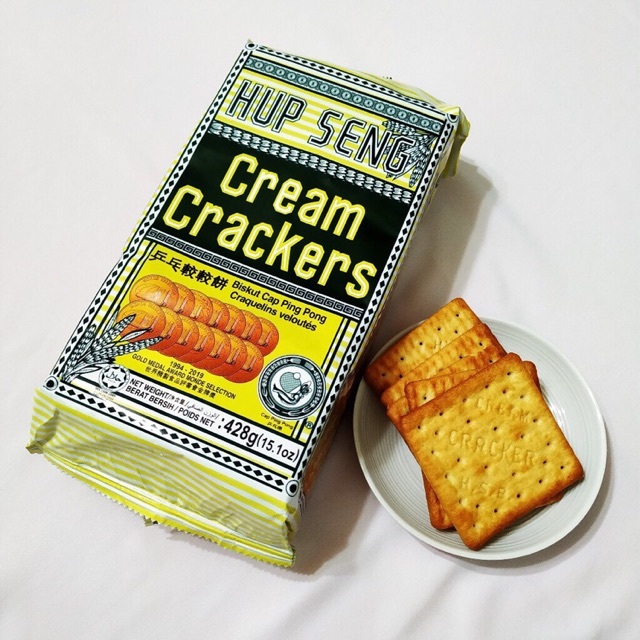

4. Hup Seng’s biscuits were inspired by kuih raya

You probably have a packet of their cream crackers right now in your pantry. But if you pay attention, you might notice the small ping pong logo on the package.

Back in the 50s when our editor was born, the 4 Kerk brothers pooled together RM1,500 (around RM9,000 today) to start a business selling biscuits and confectioneries from town to town using a van. Then in 1957, they decided that it’s time to make their own biscuits instead and rented a shop lot where they started some R&D.

Their very first product, Cap Ping Pong cream crackers, was probably their most successful. It was given that name as China was the world table tennis champions when the crackers were released in 1958.

But the inspiration for their subsequent biscuit products is actually quite Melayu – kuih raya.

They lived in Parit Linau Kecil in Johor, where there were 100 Malay families and only 7 Chinese families, which also meant they had 100 opportunities to sample all the kuih raya. Consequently, they also made sure their biscuits are halal since they first started in 1957.

But despite the variety of biscuits they have now, we all know which one we’re having with our coffee every morning.

5. Julie’s was chosen because other brands used Chinese names

You might have seen some of Julie’s new ads, as they’ve been trying to update their image, which included a change to that iconic blonde girl in their logo.

But the name Julie’s wasn’t based on a real person. According to their lore, just as the first batch of cookies were out the oven, Su Chin Hock, Julie’s founder, was already thinking of expanding overseas. Back in the 80s the domestic market was saturated with biscuits with very Chinese names, so he wanted to try something different.

He also thought that their proposed brand name was very long and didn’t like it. And out of nowhere, he just decided on that name: Julie’s. The current company director, Martin Ang, confirmed that it wasn’t based on any of his past girlfriends.

This sponsored content is brought to you by… jk it’s not sponsored (but email [email protected] if you nak sponsored content). Kbai

- 6.5KShares

- Facebook6.2K

- Twitter28

- LinkedIn20

- Email21

- WhatsApp235