How did Malaysian beef become more expensive than imported beef!?

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn10

- Email16

- WhatsApp49

With Raya season coming up, those of us who eat beef will again be reminded of how expensive they can be, even if the price usually gets controlled by the government during times like these. In Kedah, for example, prices have already been reported to rise up to RM34-35 per kilogram as opposed to the previous RM32-33 per kg, and the reason had been an increase in demand.

According to Omar Ismail, Kedah’s Ministry of Trade and Consumer Affairs (KPDNHEP)’s Head Enforcer, this often happens near festive seasons.

“Some traders only carry out their business of selling local beef during festive seasons. There are those among them who took advantage by raising the selling price higher than it’s supposed to be, as they know the demand will skyrocket,” – Omar Ismail, translated from Berita Harian.

Guess it’s better to eat chicken for now, as they only cost like RM7 or so per kg.

But what if you die die want beef? Well, maybe look for the frozen imported one, which may actually be cheaper. Yep, perhaps surprisingly, in the case of beef, buying import may actually save you money instead of buying local, particularly if the beef is imported from India. In a sort of topsy-turvy kind of logic…

It’s actually cheaper to import certain kinds of meat than make our own

When it comes to our non-vegetarian food production, Malaysia is not doing too badly in terms of eggs, poultry and pork. But red meats like beef and mutton had been a bit of a headache for some time already. Although in recent years our cattle production had been on the rise, we’re still pretty far from being self-sufficient. Local demand for beef is about 191,000 tonnes per year, but in 2017 we only produced 52,000 tonnes. That’s only about 27% of our needs, so the other 73% had to be imported.

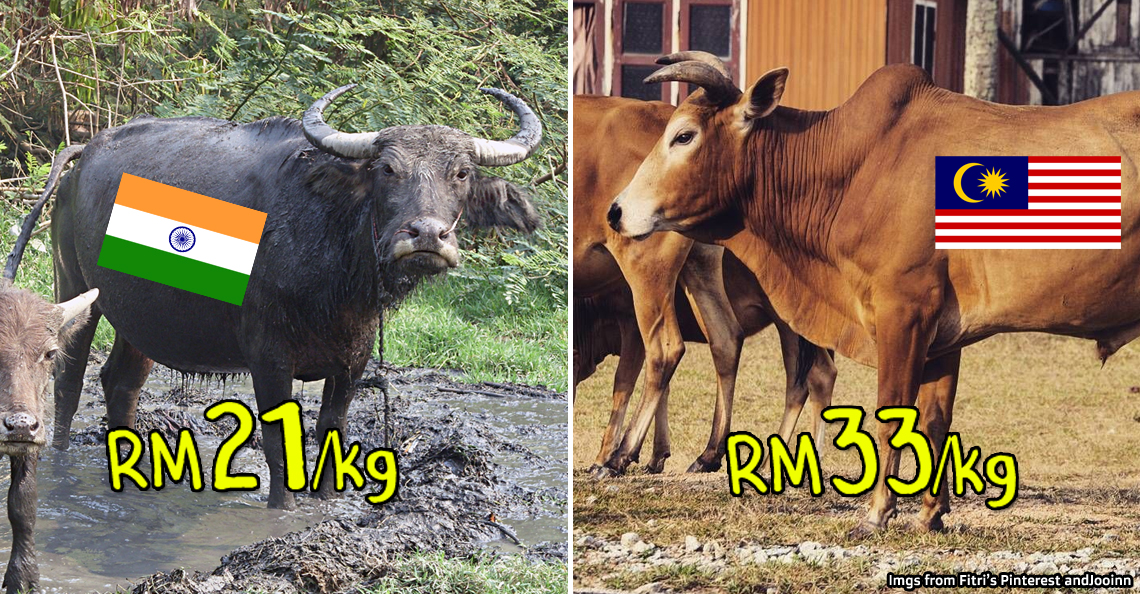

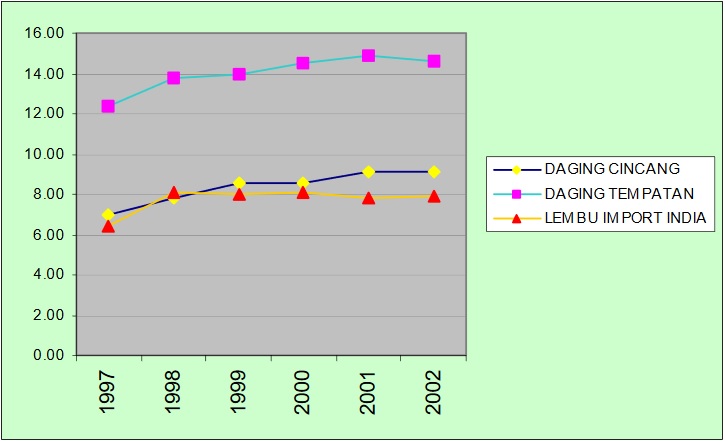

Every year, Malaysia is said to import RM1.14 billion’s worth of beef, with most of it being buffalo meat from India (70%) and the rest coming from Australia, Bangladesh and Pakistan. And despite being imported, buffalo meat had always been a lot cheaper than local beef, even as far back as 1997. In June last year, local beef had been priced at about RM33 per kg, while imported buffalo had been around RM21 per kg.

This cheapness of foreign meat is part of the reason why we’re still importing it, according to Datuk Dr Quaza Nizamuddin, the director-general of the Veterinary Services Department. He had revealed that local mutton are also more expensive than those imported from Australia, and the reason why had something to do with the cost of rearing these cows and goats.

“Australian goats are usually feral while the sheep are reared for its wool. Exporters need only to send them here for slaughtering. The cost of production is practically zero.” – Datuk Dr Quaza Nizamuddin, to NST.

Goats are relatively not that cost-intensive, as they can be slaughtered as early as 8 months old, but cows take around two to three years before they’re heavy enough to be slaughtered. During that time, a significant chunk of the cost goes towards the feed: for cattle, up to 19% of their total cost. Raw material for the feed (most commonly corn) is typically imported from other countries, although some use local feed made of oil palm-based materials. Letting your cattle just eat grass may be a cheaper alternative, but there’s a lack of land for grazing in Malaysia, and natural grasslands here can’t grow grass fast enough to support more cows.

Although there had been success stories in cattle farming, due to the high cost and price control lowering the profit, not many people are keen to rear cows, using their land for more profitable ventures like poultry farming. So the struggle here is to get more people to make more local beef and consequently get their prices down a bit, and over the years the government had tried a few approaches to do that.

Perhaps most notably, when it comes to rearing cows…

We’ve had a very expensive plan that didn’t go anywhere

Even if you’re not in the beef business, you’ve probably heard of something called the National Feedlot Corportation (NFCorp), or its project the National Feedlot Center (NFC), or perhaps ‘cowgate‘ or ‘that cows and condos scandal‘ over the years. Politicking and jabbing aside, what the heck was that? Well, feedlotting is basically rearing cattle in confined spaces (called feedlots), and by feeding them and limiting their movement, it’s supposed to make them grow faster.

During the 9th Malaysia Plan, the Negeri Sembilan state government agreed to support the federal gahmen and established a Beef Valley in Gemas, with the National Feedlot Center at the center of it. The NFC was meant to commercialize and integrate feedlot farming of cows, as well as creating a system of contract farming where the NFC breeds cows and sends them to be fattened up at satellite farms by contract farmers, then buys the cows back.

However, three years later, an audit found several issues with the program, like technically having no contracts with farmers, one of the main operators pulling out, the grass fields overgrown with acacia, and other management problems that you can read in full starting page 136 of this audit report. Perhaps most importantly, the NFC only reached less than half of their target of 8,000 cows in three years, only managing to come up with 3,289. This was even after they received a soft loan of RM250 million from the government, which remained unpaid as of the time of writing.

Since the audit report, the opposition at that time had claimed that the company, run by a minister, her husband and two children, had suffered from financial mismanagement and corruption. The soft loan was alleged to have been used to buy condos, cars and for holidays, and most of the beef produced allegedly went to restaurants owned by the family. We won’t go too deep into that, but suffice to say that it had been a pretty big issue.

While there had been debates on whether or not the NFC failed, the Malaysian Insight reported last year that the NFC in Gemas lay abandoned, with a worker at a nearby oil palm estate saying that no one had been there for the past four years.

“You can see a huge block of buildings there, and one of them was used as a quarters for the workers. The signboard is not that clear so watch out for the water tank. No one stays there any more. No livestock, no workers,” – anonymous oil palm laborer, to the Malaysian Insight.

Despite that, a 2017 report mentioned that there are 15 locations being used as satellite farms under the program, which produced 1,317 tonnes of beef the previous year. So maybe only the Gemas NFC is dead. We dunno. Their website refused to share their secrets. Regardless of whether or not it’s still alive…

The NFC will be revived, but will it be any different this time?

Well, the name will be different, at the very least. Barely a month into Malaysia Baru, the government announced that the NFC will be revived with a different business model and renamed. This is because we have to do something about our self-sufficiency when it comes to beef, and the Vet Services Department had already set up 61 standalone satellite farms to support the NFC, so might as well improve them and revive the NFC anyway.

As for what’s new, the Agriculture Minister Salahuddin Ayub had said that the revived NFC will be more private-sector driven, with a ‘more business than government approach‘. The ministry is also looking at increasing the participation of government-linked companies which have plantations as their core business, like Felcra Bhd and IOI Group.

“Some GLCs have resisted because it is not their core business and that the returns are not as attractive, but we hope this can change. They should consider this as national service in helping the government increase its food production and self-sustainability. We want to speak to the owners of these plantations. We can put in and rear more animals in the system.” – Salahuddin Ayub, to NST.

However, Sam Lau, a retired vet who took part in the planning of a feedlot program for a neighboring country, had said that the new model does not seem that much different from the old one. He mentioned that our program have overlooked a glaring aspect of feedlotting: the feed, and feeding. Malaysia have little industrial biomass (like oil palm waste) that can be processed into animal feed, so we rely too heavily on imported grains, which can really raise the cost. As such, he suggests for the new model to include feed manufacturers as well.

Whatever plans there are for the NFC in the future, Salahuddin had confirmed that a there is indeed a local corporation interested in buying over NFCorp, and that corporation is said to have expertise in the ruminant industry. Even better, the company is also said to be willing to settle NFCorp’s loan to the government. For now, it’s still in the discussion stage, but if everything works out fine, hopefully we can upgrade from just plain Maggi mee sometime in the future.

- 1.2KShares

- Facebook1.1K

- Twitter10

- LinkedIn10

- Email16

- WhatsApp49