The unsolved mystery of Malaysia’s first hijacked airplane

- 6.7KShares

- Facebook6.4K

- Twitter47

- LinkedIn5

- Email82

- WhatsApp206

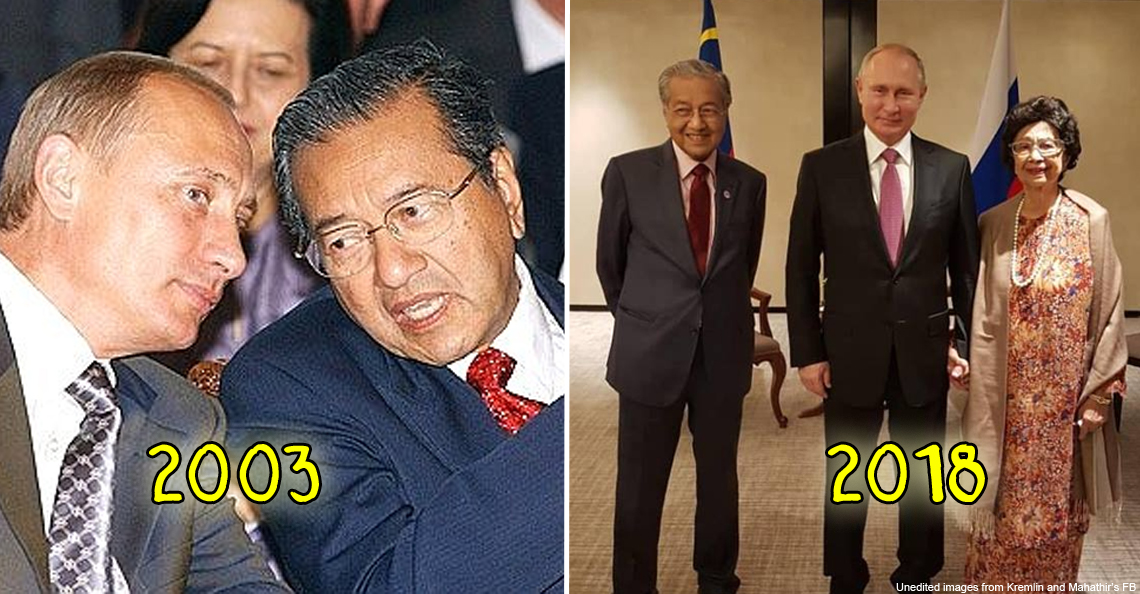

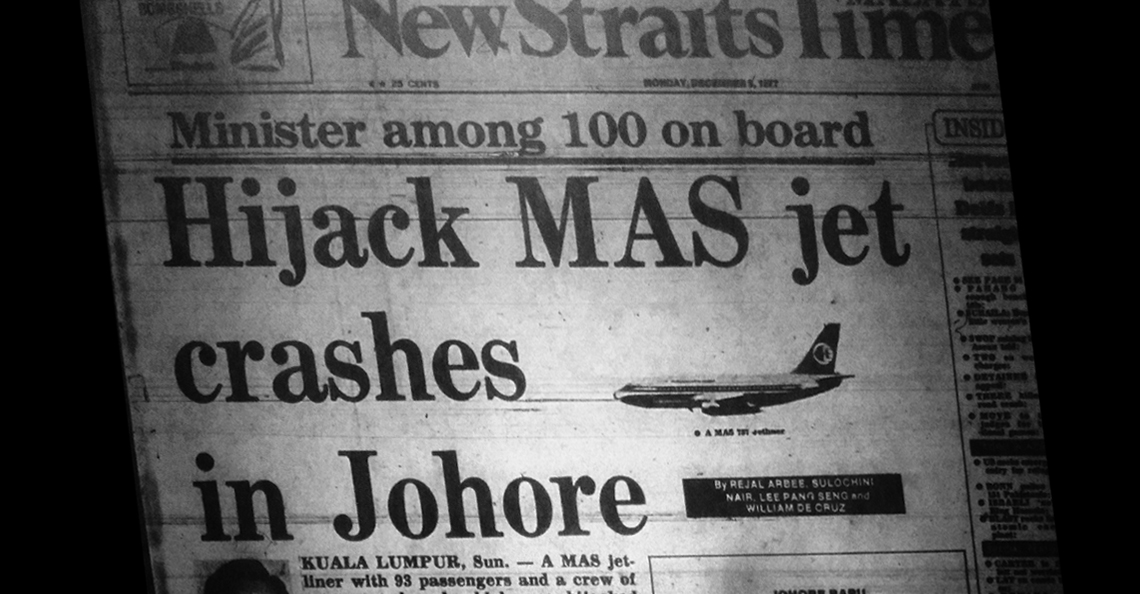

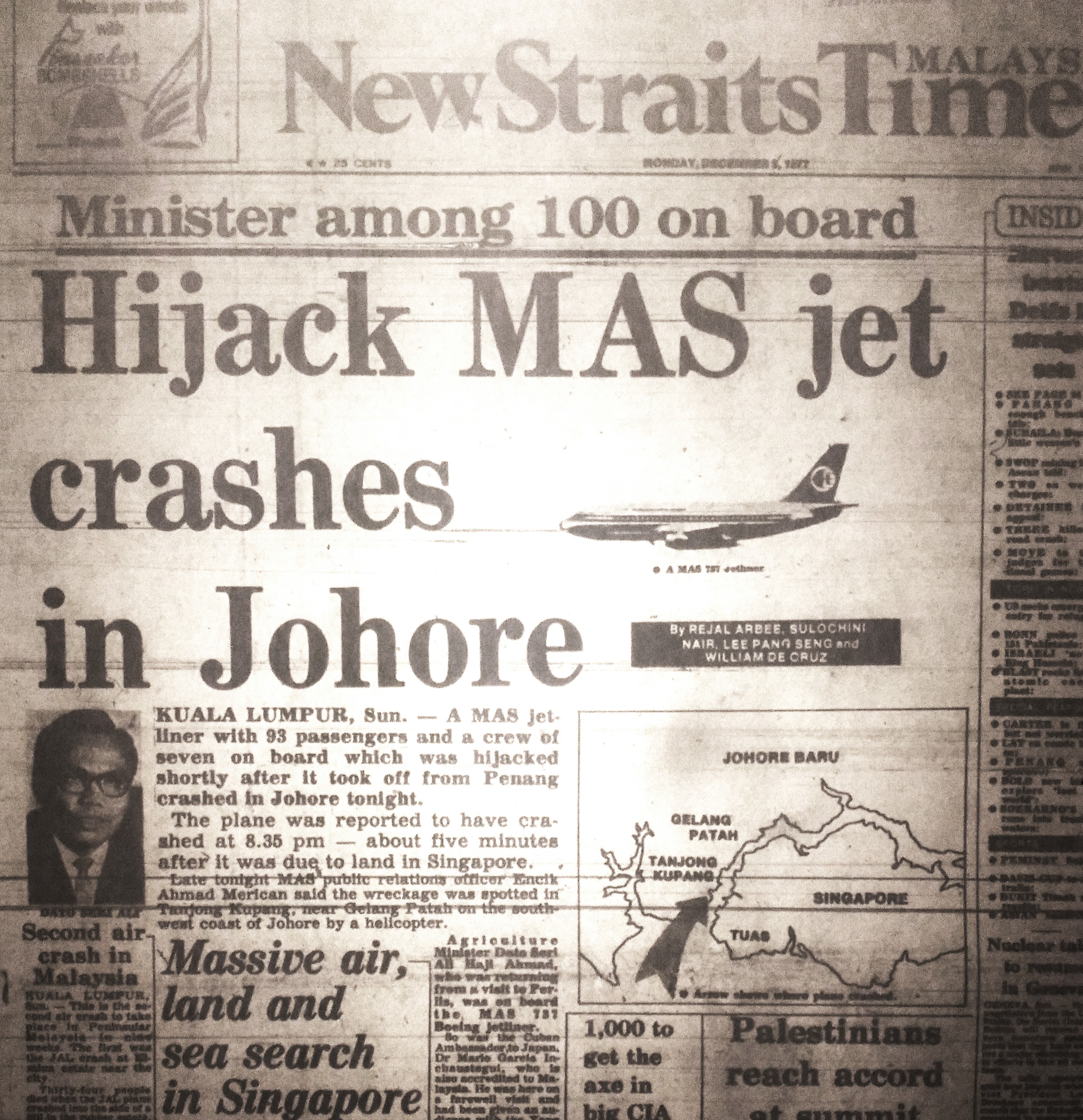

Two days ago, it would’ve been exactly 3 years since MH370 disappeared. That same year, we also had the tragedies of MH17 and also AirAsia’s Q85301. Thankfully, since then… Malaysia’s luck with aeroplanes has gone back to normal. But before those incidents, waaaaay back in 1977, the Malaysian aviation industry had its first unfortunate spotlight, with one of the deadliest hijackings in history: the flight of MH653 en route to Subang Airport.

A hundred people had lost their lives in the incident but unfortunately, much like MH370, many questions about the events that took place during the hijacking have yet to be answered.

The alarming recordings of a flight gone horribly wrong

It was the 4th of December, 1977 at Penang Airport, with flight MH653 scheduled to take off at 7.15pm en route to Subang airport. On the passenger list were a couple of VIPs – then Malaysian Minister of Agriculture, Datuk Seri Ali bin Ahmad and the Cuban ambassador to Japan Mario García Incháustegui.

The day started with controversy – one of Datuk Seri Ali’s bodyguards was allegedly carrying a firearm that he refused to give up before boarding the flight. They were eventually allowed on board.

Up in the cockpit, Captain G. K Ganjoor sat down and started pre-flight checks. It was a double-anniversary for him – the day he got his pilot’s license, and a few years later, his wife as well. The plane took off without a hitch, and less than half an hour later, they were nearing their destination of Subang airport. This is where MH653’s recovered black box begins to tell a violent story.

Capt. Ganjoor had just pulled out his landing gears when he heard a knock on the cockpit doors. He asked his co-pilot what was going on, before yelling back that the door was unlocked. Someone then barged in – it was the hijackers.

“Out! Cut all radio contact! Cut all radio contact – now!” – Alleged hijacker, from the MH653 black box transcript

If Capt. Ganjoor was panicking, he didn’t show it. He asked the hijackers where they wanted to go, adding that the plane only had enough fuel for Singapore at best. The hijackers, without much of a choice really, eventually told the pilots to inform airport authorities that they’re going to Singapore.

The pilots obliged. Capt. Ganjoor also told his stewards to reassure his passengers to prevent panic.

“Now, don’t say anything to the passengers okay. I don’t want any nonsense from passengers… merely tell them that we are diverting to Singapore, due to weather or whatever okay… tell them nothing, it’s alright and we’ll leave the doors locked.

Just close it now – relax – serve the passengers if you want,” – Capt G. K. Ganjoor to his stewards, from the MH653 black box transcript

MH653 was now over Malacca, quickly approaching Batu Pahat. With their impromptu destination nearing, the hijackers were starting to become restless and annoyed with the pilots. Perhaps they were panicking, worried that the pilots had lied to them. Perhaps afraid that the pilots had signalled for authorities to arrive the moment they landed, the hijackers did the only thing they could think of – shoot the pilots dead.

At 8.33pm, a gun shot was heard….

“No, please don’t – *gun shot* no… please no…. *gun shot* please, oh….” – Capt G. K. Ganjoor, from the MH653 black box transcript

After the sounds of gun shots, various sounds of alarms and notifications were going off in the cockpit. Recordings from the black box seem to suggest that after killing the pilots, the hijackers failed to take control of the plane themselves. Witnesses claimed that they saw the Boeing 737 go upwards and downwards in sharp angles repeatedly.

It seems as if after shooting the only people who could fly the airplane, the hijackers put in place a death sentence for themselves and everyone else onboard.

The crash

“I heard two explosions and then something went down and I saw a huge fire. At first I thought it was part of Singapore’s military exercises, but then I saw an RM50 note and something that had a MAS logo. That’s when I realised what really happened,” – Sulaiman Osman, MH653 crash witness

At 8.36pm, MH653 crashed in Tanjung Kupang, Johor. Several eyewitnesses claim they saw an explosion before it hit the ground; the official investigation report claims otherwise.

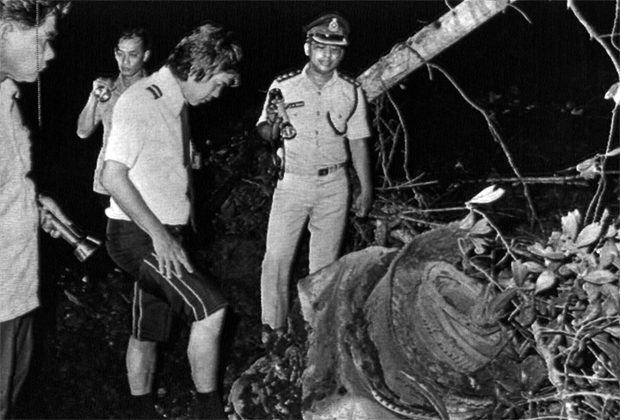

Search teams and investigators soon reached the crash site, looking for survivors, bodies, clues, anything really. But sadly, there were no survivors and not even an identifiable body found at the crash site. It got to the point where they stopped bringing stretchers and brought polystyrene bags to collect any charred body parts that they found.

All remains that couldn’t be identified were buried in a mass grave.

Unfortunately, neither the black box nor the evidence from the site could answer one major question…

So who were the hijackers?

In the years since the crash, many theories have sprung up regarding the identity of the hijackers. Some of the more common theories include Vietnamese militants, as Singapore had recently arrested 3 Vietnamese militants responsible for a hijack of an Air Vietnam plane. Then there’s also suggestion that it could’ve been Cuban terrorists (hijacking was trending among Cubans those days) as Mario García Incháustegui was on board MH653.

On top of that, another theory involved the bodyguard of Datuk Seri Ali bin Ahmad who accompanied his employer on the flight. Remember that alleged scuffle prior to departure where Datuk Seri Ali’s bodyguard didn’t wanna give up his gun? After the crash, a rumour went around claiming that he was the hijacker. This theory gained enough traction that it was even discussed in Parliament. The conspiracy theory went even further, with some suggesting that the lack of an official reason was a cover up to protect the image of Datuk Seri Ali.

However, one of the strongest theories about who’s behind the hijackings were the Japanese Red Army.

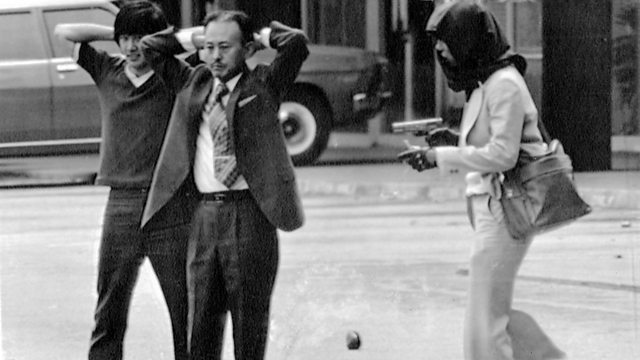

The Japanese Red Army (JRA) were a group of militants that formed in 1971. They originally made their goal the overthrow of the Japanese government and monarchy, as well as wanting to ignite a world revolution. The JRA had been pretty active in the 1970s, with some of their more notable acts of terrorism including the hijacking of Japan Airlines Flight 351 in 1970 and the Lod Airport Massacre in 1972.

MH653 wasn’t even their first involvement in Malaysia – the Japanese Red Army had been behind the infamous AIA Building hostage crisis in 1975. Ugaiz can read more about the hostage crisis over at our sister site Soscili!

While this remains one of the strongest theories to date, both the Malaysian Home Ministry and the Japanese government deny the hijacking was carried out by the Japanese Red Army.

Identities aside, the other mystery that has yet to be answered is how did the hijackers get on board in the first place?

“Thirty-seven years down the line, we still don’t really know the truth,” – Ruth Parr in 2014, who lost her father in the crash

But it’s quite hard to tell… cos anyone could get into an airport those days

The Penang Airport was never known for having good security. The security there was so bad that the International Federation of Airline Pilots’ Association had listed its security as “criminally deficient“.

Meanwhile, journalists from The Star decided to do some investigative work immediately after the crash and had found that the security in place was “hopelessly lax”. They found that the gate for cargo and VIP access to be open with no guards in sight. The fencing around the airport runway was also opened up, due to the construction of a new airport terminal going on at the time.

But perhaps the most damning case of airport security fail to happen at the Penang Airport was that a month before the crash someone actually made it past security without a ticket and got on a MAS plane. He was only found out when a passenger complained that there was someone sitting in his seat. But that wasn’t an isolated case… Just one week before the hijacking, four men made it past airport security and made it all the way to the tarmac before finally being caught.

The tragedy of MH653 forced the gomen to make airports safer

Although MAS announced that they would be paying the families a collective RM8.8 million in compensation (quite a lot of money in the 70’s), it didn’t do much in providing closure for the families of the victims:

“People keep talking about closure but in a case like this… there will never be closure because you always have that sense of loss, that grief, that missing person from your life,” – Devicka, Capt G. K. Ganjoor’s daughter

However, the tragedy, along with the great investigative work of The Star’s journalists, exposed the flaws and weaknesses in Penang Airport’s security which led to massive changes in the Malaysian aviation industry.

One of the biggest changes that occurred as a direct result of the MH653 crash was the introduction of the Aviation Security Unit, which was set up to “safeguard domestic and international civil aviation against acts of unlawful interference” as well as to ensure that the security measures within an airport are up to national and international standards.

Airport security meanwhile started being a lot tougher, with more thorough checks on passengers and cargo occurring. VIPs were also no longer exempted from checks before boarding.

So while the mystery of the hijacking may never be fully solved, it served as a wakeup call for the authorities that security is an ongoing process. Similar to how the 9/11 attacks started an international wave of security reforms, a smaller, local version of that happened in 1977. While, the MH653 tragedy remains a dark spot in Malaysia’s aviation history, but also became the catalyst for a lot of positive change, which perhaps saved a lot of people in the decades since.

- 6.7KShares

- Facebook6.4K

- Twitter47

- LinkedIn5

- Email82

- WhatsApp206