Can you guess which endangered animal gets killed by Malaysian drivers the most?

- 655Shares

- Facebook599

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn11

- Email8

- WhatsApp30

If you drive around in Peninsular Malaysia a lot, you might have seen this sign:

That’s supposed to be a silhouette of a tapir, but perhaps you’ve seen the same sign with a cow or a deer or maybe an elephant outlined on them. Whatever animal are on them, these signs warn drivers that there’s a good chance a wild animal will cross the road, so they should probably slow down. However, some Malaysian drivers keep hitting wild animals with their cars and trucks, and whether it’s accidental or not, it’s turning out to be a huge problem.

In February, a 250 kg male tapir was killed by a car in Pahang, and in December last year, a sun bear as well as another tapir was killed in separate road accidents on the peninsular, with the tapir’s carcass mutilated by the nearby community.

Pshaw, you may say. Those are isolated incidents, so there’s no need to exagge-

Within five years, almost 2,000 wild animals have been killed in road accidents…

…which brings the average to almost 400 wild animals a year, or at least one wild animal a day. In 2016, Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, the Natural Resources and Environment (NRE) Minister had cited the deaths of some 1,914 wild animals in road accidents. Even though the most common wild animals killed during that period were monitor lizards and macaques (667 and 393 cases respectively), the number also included threatened, rare animals, like bearcats, elephants and even tapirs.

Yep, while we rarely see the adorable diaper-wearing black beasts in the wild, it would seem that tapirs are the most common threatened wild animals to meet its end on the roads.

“Most of the wildlife killed are from the endangered species such as tapirs, sun bears, elephants, mountain goats and tigers. I was told that tapirs were among the highest victims in roadkill incidents. Perhilitan records show that 43 tapirs were killed in road accidents in the last five years.” – Datuk Dr Hamim Samuri, deputy NRE minister, for The Sun Daily.

Johor recorded the highest number of incidents during that time (494 cases), followed by Kedah (479) and Perak (394), but Hamim Samuri revealed that most of these incidents occurred on five roads in Malaysia, and they are:

- Jalan Kuala Lipis-Gua Musang

- Jalan Kulai-Kota Tinggi

- Jalan Gua Musang-Kuala Krai

- East Coast Expressway

- Jalan Taiping-Selama

While the number of reported cases are shocking enough, the actual number may be even higher. In the US, their Federal Highway Administration (FHA) reported around 300,000 wildlife-vehicle conflicts (WVC) for 2008, yet it estimates that the real number of collisions to be somewhere between one to two million, as many go unreported. This may hold true in Malaysia as well, as the recent tapir death was not reported, and the authorities found the carcass several days later.

This brings us to a corny yet important question…

Why did these animals cross the road anyway?

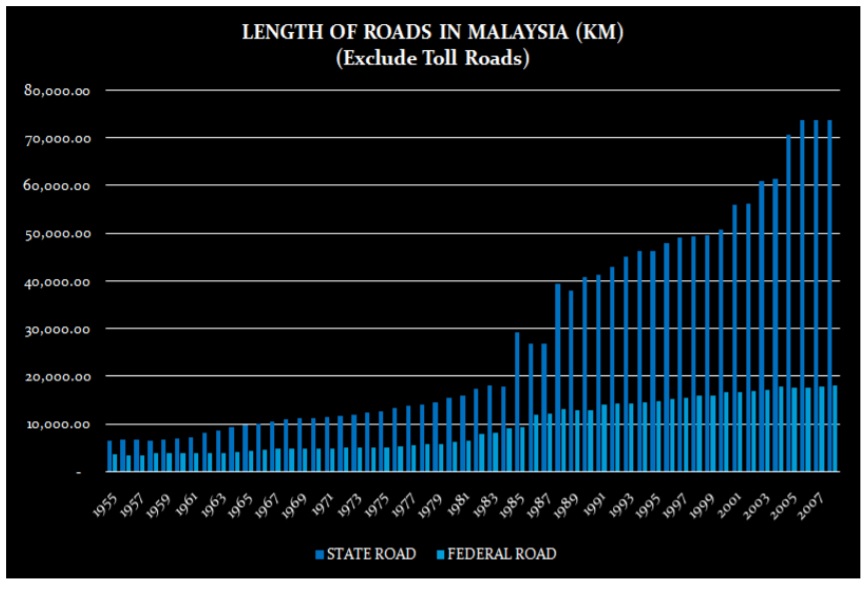

The answer to that should be ‘to get to the other side’, where, according to Datuk Dr Hamim Samuri, there are shelter, food, mates and habitats. But the real answer may be the same as the answer to another corny question, which is ‘because it’s there‘. Malaysia is developing, and the more developed it gets, the more roads it needs. According to the World Road Association, the amount of roads in Malaysia had been rapidly increasing since the 1980s.

These roads connect more places in Malaysia, but at the same time they separate the forests they run through into islands. This poses a problem for the wildlife living in those forests, as certain routes they usually take may be blocked by roads. Imagine a river suddenly appearing between your living room and your kitchen, and you’ll see that in the case of Malaysian wildlife, one may say that it’s the road that crossed the tapir (path) instead of the other way around. Or something.

Anyway, the Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM), in an open letter, had blamed the number wildlife road accidents on the reckless planning and construction of new roads, and in recent times, these developments happen on the east coast of the Peninsular. The newly-completed East Coast Highway 2 was said to have recorded the highest cases of roadkill, and the building of the East Coast Rail Line (ECRL), a high speed train which will connect Port Klang to the East Coast, have been criticized by environmentalists for cutting through several major rivers and hundreds of hectares of protected forests, further fragmenting them.

This brings up a dilemma: on one hand, we need to connect the east coast with the rest of Malaysia, but on the other hand, the infrastructures to do so are a hazard to wildlife. This may be an easy decision for some people one way or the other, but the government believes that…

Theoretically, we can have our roads, and keep our wildlife too

Have you ever heard of something called the Central Forest Spine (CFS)? Earlier, we talked about how roads are cutting up the forests on the Peninsular into isolated patches, and the CFS is the government’s solution to that problem. Basically, how it works is that we connect all these isolated patches to one another using various methods to make sure that all the fragmented forests on the Peninsular form one long, unbroken forest. If it succeeds, a Johorean tapir can probably travel all the way to Perlis without ever having to set foot on a road.

This can be accomplished through viaducts, which are elevated road structures, and they look something like this:

Or they may also be accomplished by wildlife crossings, like this one:

Or tunnels, or basically anything that gives wildlife a safer alternative to cross over. However, just as you can’t expect humans to use pedestrian bridges just because they’re there, you can’t also expect wild animals to use the safe crossings provided to them… which is why electric fences (or just plain fences) are used to discourage wild animals from crossing anywhere but the green roads, and initiatives like salt licks and animal food are sometimes placed/planted at a new viaduct to lure animals there.

“It has been positive to see a lot of wildlife have been using the viaducts – elephants, bears, tapirs, deers, wild boars and smaller animals like civet cats and flat-headed cats,” – Dr Pazil Abdul Patah, director of Perhilitan’s Department of Biodiversity Conservation, for Channel News Asia.

But there’s only so many viaducts and tunnels you can build, so for stretches where there are no such crossings, the government had been focusing on making the drivers slow down and be cautious when passing through. This includes the installing of wildlife crossing signs (like the one at the start of this article) where animals are very likely to cross, lighting up those areas, and installing transverse bars on the road.

Other than that, the Perhilitan is also planning to team up with driving schools across the country to incorporate wildlife crossing awareness into driving lessons, as well as reaching out to Waze to include alerts on roadkill hotspots.

“There is a pattern in the occurrence of roadkill involving endangered species… We are trying to get Waze to highlight these hotspots on its app, so that people will be more aware and slow down their vehicles when approaching such areas,” – Gilmore G. Bolongon, Perhilitan’s biodiversity conservation division assistant director, for the Malaysian Insight.

Due to the high incidence of tapir-related accidents, the government had even launched a program specifically for them in Johor, called the ‘Safe Tapir Crossing‘ program. However…

Will all these initiatives reduce the number of tapir accidents?

While the government seemed to have done a lot to reduce the number of wild animal road deaths in the past few years, as the Sahabat Alam Malaysia and the statistics pointed out, there doesn’t seem to be much difference in the number of roadkills. Tapirs are classified as a completely protected species, and it was estimated that there are at most only 1,500 of them left on the Peninsular. With an average of 7 tapirs being killed by motorists a year, things aren’t looking good.

So what can we do about all this? Well, first of all, if you see fences on the sides of the highway, do not cut or damage it. Damaged fences had also been quoted as a reason for the high number of road kills on the East Coast Highway, and it’s not for a lack of upkeep.

“This is because although there has been effort to build fences, every fortnight or so the Malaysian Highway Authorities have to fix it because humans cut through it.” – Abdul Kadir Abu Hashim, Perhilitan director-general, for the Malay Mail Online.

Wan Junaidi had stated that the fences were cut by people living in the area to make it easier for them to go into the estates, and this constant form of vandalism had cost the authorities a lot of time repairing the fences, which could be used for other things.

Another (kind of obvious) thing to do is to drive more carefully, and not just to save the tapirs. Within the first nine months of last year, 5,083 people died on Malaysian roads, and the total number of accidents reached 400,788 cases. So, yeah. Tapirs aren’t the only ones endangered here. It helps to be more patient on the road, and even though the roads may be empty, do slow down and be careful if you see an animal crossing sign.

But what if you do hit a wild animal? The right thing to do is to call up the Perhilitan at 1-800-88-5151 any day of the year and report the incident so they can take care of it. And based on our anonymous Perhilitan source, no, you won’t get fined for it. Probably.

- 655Shares

- Facebook599

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn11

- Email8

- WhatsApp30