Malaysia might’ve broken UN laws by sending this Thai woman back home

- 259Shares

- Facebook210

- Twitter12

- LinkedIn10

- Email10

- WhatsApp17

The last 9th of May marked one year of Malaysians being under a new government, and for many, the date represented the birth of a better Malaysia. A number of media outlets (including us heheh) published a commemorative piece to honor the occasion. Everything is good in Malaysia Baru, but the very next day, something happened that shook quite a few people’s faith in the new government, yet again.

No, we’re not talking about the new suggestions for PTPTN borrowers, but something less relatable to most Malaysians, if we’re being honest. On May 10th, a Thai woman by the name of Praphan Pipithnamporn was sent back to Thailand by the Malaysian government, and human rights groups were not amused.

As for why they’re not amused, Praphan is recognized as an asylum seeker by the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), meaning that she ran away from Thailand because she was threatened by something, and the UN felt her fear was valid enough. By returning Praphan to Thailand, as a crude analogy it’s like returning an abused girl to her drunk dad, even if you know she’s gon’ git her ass whupped.

To make things worse, by sending her back, Malaysia might have broken some customary international laws. But before we get to that dry part, you might be wondering…

Actually right… is this Praphan person really in danger?

Well duhhhh she’s an asylum seeker registered with the UN, you might be saying. However, if you’ve read one of our past articles, you might be aware that some people may go to other countries to ask for protection under doubtful circumstances *cough* citizenship shortcut *cough*. There may be a reason to doubt Praphan’s asylum-seeker-ness. So what happened to her that could be so bad, she had to leave?

Insulting royalty, that’s what. Praphan was reported to be a supporter of a network that encourages people to overthrow the monarchy, and she was first arrested while she was protesting the monarchy last year, handing out leaflets attacking the royal family at a shopping mall. On December 5th, during the birthday commemoration of the late King Bhumibol.

If you think that Malaysians had to tiptoe when it comes to making comments around our royals, Thai people would probably faint with shock at the things we get away with. In our country, alleged insults to royalty fall under the Sedition Act, but in Thailand, they have something called lèse majesté, which is French for ‘to do wrong to majesty’. And while Malaysia’s Sedition Act said that some things may not really be seditious (Section 3), Section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code states that:

“Whoever, defames, insults or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years.“

That’s a lot of wiggle room you can use to put people in jail. In the past two decades, more and more people have been investigated and imprisoned under this law, for doing stuff like gossiping about the king in a taxi, making fun of the king’s pet dog, liking a Facebook post critical of the king, talking about real history (that makes the king’s ancestors look bad), and writing a novel with characters that resemble the royal family, to name a few.

Practically anyone can accuse anyone else of lèse majesté, and each complaint have to be taken seriously by the police, probably because if you think about it, not taking lèse majesté seriously is lèse majesté in itself. According to UN numbers, since Thailand’s 2014 military coup, the number of people investigated for lèse majesté had doubled, and those charged are rarely acquitted. This is perhaps why some have dubbed Thailand’s lèse majesté laws to be the world’s harshest. Even in our past article about the harshest punishments people ever got for posting stuff on the net, the crown went to a Thai man who got 70 years (reduced to 35 for pleading guilty) for insulting Thai royalty on Facebook.

Interestingly though, Praphan wasn’t charged with lèse majesté, but rather for sedition and belonging to a secret society. After being released on a 200,000 baht bond (RM26k-ish), she fled to Malaysia around February and applied for asylum. In early April, the UNHCR registered her claim as an asylum seeker and designated her as a ‘person of concern‘, meaning that she should be safe from being sent back to Thailand. Well, as it turned out, nope.

In spite of people raising a stink about it now, we wondered if we’ve sent other foreign wanted people back to their home countries in the past. Well…

It seems that different rules were used for different cases

Apparently, the reason why Malaysia sent Praphan back was because Thailand asked for her. In the words of the Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad,

“If there is a request, then we will send back. (We are a) good neighbour,” – Dr Mahathir, as reported by the Star.

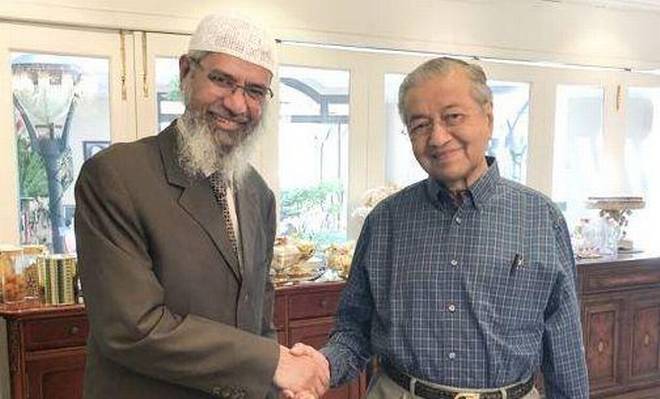

But has that always been the policy? We couldn’t find an exact same case as Praphan – an asylum seeker registered with the UN sent back on the home country’s request – but we can perhaps compare to somewhat similar cases. Perhaps the lowest hanging fruit that comes to mind is the case of controversial Indian preacher Zakir Naik, which had been brought up by several people after Praphan’s repatriation. Zakir is not really an asylum seeker, but he was given permanent resident status by Malaysia sometime around 2012.

Zakir has been charged for various crimes under the Indian Penal Code and Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, and they are still trying to get an Interpol Red Notice on him. Despite calls for Zakir to be deported, the government’s stand (as of July 2018) had been to let Zakir stay on account of him being a permanent resident, with the PM saying that Malaysia will not easily give in to demands made by others, lest someone becomes a victim. So that’s a 180° from Praphan’s case.

Two months ago, Malaysia deported six Egyptians and a Tunisian amidst protests from human rights groups. It was believed that these seven men face possible torture and persecution in Egypt, and Amnesty International Malaysia had urged the Malaysian government to reconsider. These men were aligned to Mohamed Morsi, former President of Egypt who was forcibly removed during Egypt’s 2013 coup d’état. However, they were detained under Sosma in Malaysia and later deported over security concerns, being suspected of having links to foreign Islamist militant groups.

“As the presence of these foreigners constitute a security risk, all suspects have been deported to their native country and… recommendations have been made to blacklist them from entering Malaysia for life,” – former IGP Mohamad Fuzi Harun, as reported by NST.

Last year, Malaysia detained 11 Uighur Muslims running away from China, and China wanted them back. Despite a lot being at stake, Malaysia decided to release them from detention and send them to Turkey instead, ignoring China’s request. It should be noted that back in 2011, a different batch of 11 Uighur Muslims were in Malaysia, and we took a different decision back then and deported them back to China.

In 2017, three Turkish citizens were forcibly deported for suspected allegiance with a group Turkey called the Fethullah Terrorist Organization, and in 2012 a young Saudi journalist accused of insulting the prophet Muhammad on Twitter was sent back amidst reported death threats and criminal charges. Both incidents drew flak from international rights groups and organizations, and we can probably find more incidents like these, but the point here is… is there a pattern?

Based on these cases, it would seem that… we don’t have a hard and fast rule for it. At least, one that’s easily available to the public, anyway. We do, however, have laws regarding extradition, and you’re probably wondering…

So how many laws did Malaysia break?!

When it comes to laws regarding refugees and asylum seekers, Malaysia has no formal laws in place since we did not sign the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol (because we can’t satisfy its minimum requirements). However, even if we didn’t, our stance had been said to respect the principle of non-refoulement, which means that we don’t return refugees and asylum seekers to where they were running away from, as long as they don’t threaten our security.

This concept of non-refoulement is also a customary international law, which means that it may not be found in written treaties (this one can though), but it carries weight in international courts anyways. However, we seem to have went against the non-refoulement principle with Praphan’s return, as after her deportation the UNHCR had urged governments all over the world to uphold the non-refoulement principle. Even the Malaysian Bar was deeply concerned over the deportation, according to its president Abdul Fareed Abdul Gafoor.

“It is disheartening and troubling that the Malaysian government violated international law, and abdicated its legal and moral obligation not to deport individuals back to situations where their very lives may be in serious jeopardy.” – Abdul Fareed Abdul Gafoor, as he wrote to the Star.

He also pointed out that although we do have an extradition treaty in place with Thailand, we also have our Extradition Act 1992, the Section 8 of which outlined several circumstances where we should not give up a criminal fugitive, like if his or her crime is political in nature, or had something to do with his or her race, religion, political opinions or nationality, among other things. Hence, the Malaysian Bar had called on the Malaysian government to not overlook these provisions, and to honor, respect and uphold both the rules and customs of international law as well as the provisions of Malaysian law.

If past deportations were of any indication, there will probably no immediate consequences if the government keep on deporting asylum seekers and refugees. But it’s a new government now, and although people have pointed out that Pakatan’s reforms with regards to human rights had been a “profound disappointment” for the past year, with something like “making Malaysia a country with an internationally respected human rights record” in their list of promises (#26)… it’s probably not a bad idea for them to look into this more deeply.

- 259Shares

- Facebook210

- Twitter12

- LinkedIn10

- Email10

- WhatsApp17