Rohingya and Christian refugees share why they left Myanmar

- 631Shares

- Facebook621

- Twitter1

- Email1

- WhatsApp3

OK, so by now, you have probably read and/or heard so much about the current “boat people” situation that you might be feeling a little a lot seasick.

But it’s safe to say that regardless of how seasick you are, you are in a significantly better situation considering you don’t have to drink your own urine to survive, don’t have to fight over scraps of food (apparently, this fighting over food has led to about 100 deaths), and of course, the fact that you are not actually on a boat with your life at stake!

Adding to this seasickness are the negative comments on posts regarding this matter ranging from “I could care less” to “Just sink the boat and let them drown” to “We have had enough of PATIs (pendatang asing tanpa izin), send them back!”.

Regardless of your views on it, one good thing that has emerged from all of this madness is this: there’s now a sense of urgency to discuss meaningfully and effectively about something that has been affecting and will continue to affect all of us.

And as a volunteer teacher at a refugee learning centre in KL, this issue has always been close to my heart – so seeing how my friends have begun to talk about this topic (instead of DotA all the time) is a wonderful thing to behold.

I spoke to two Myanmar refugees – one Rohingya and the other a Christian – to learn about their story. But before that, a few things to get out of the way:

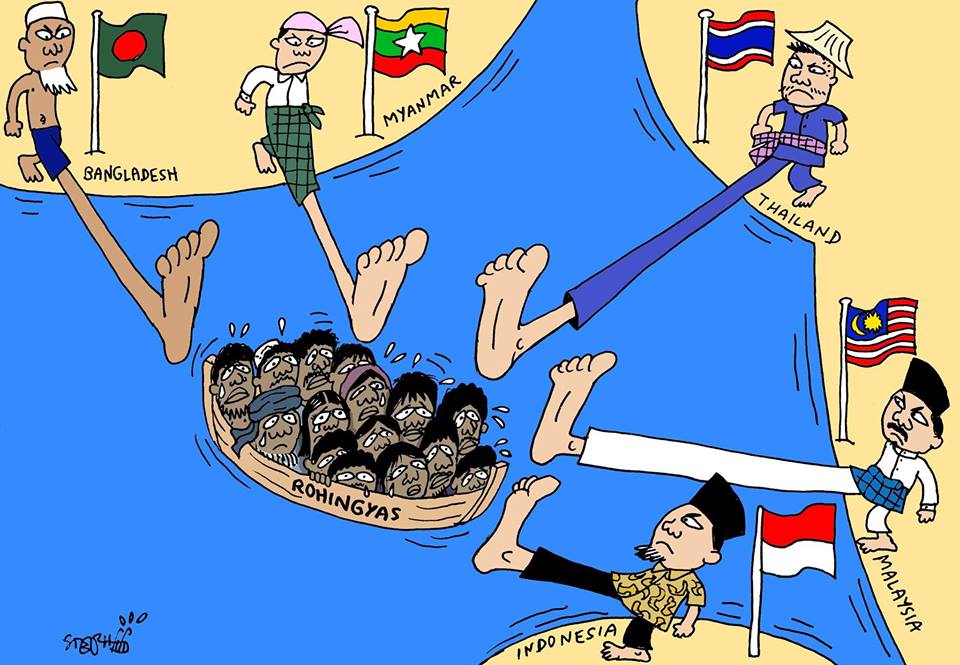

Why suddenly so many boats coming to Malaysia?

How did this whole boat sitch even start? Let’s do a real quick rundown on this.

1. Thai authorities have been cracking down on human trafficking after mass graves were discovered in Thailand (OH NO – mass graves recently discovered in Malaysia!).

2. This made the people behind human trafficking very takut for sure – because they don’t want to get caught. So these traffickers lepas tangan and let boatloads of migrants off to fend for themselves.

3. This then led the boatloads of Rohingyas and Bangladeshis appearing in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand.

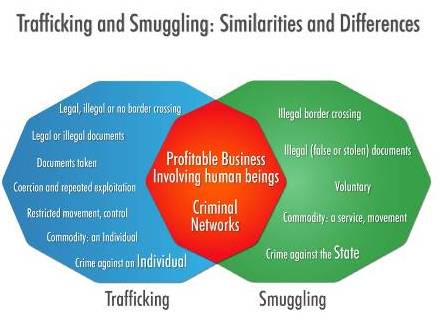

There hasn’t been any proper documentation of these migrants (UNHCR has offered assistance, fyi), so it’s quite difficult to determine whether they are economic migrants, asylum seekers or refugees – and if they were trafficked or smuggled into Malaysia. Yeah… human trafficking and smuggling are not the same.

Again, because of the so many uncertainties that exist, it’s difficult to know which category they fit into exactly, but what we can all probably agree on is that they are all victims of their circumstances – that are way out of their control lah.

Two Myanmar refugees tell CILISOS their stories

I managed to get in touch with a Rohingya refugee and a Christian refugee who were willing to share their stories for this article.

Abdul Khalaque is a Rohingya refugee who has been in Malaysia for about 25 years now. He fled Myanmar in 1990, when he was only 21 – took a boat to Thailand and then, paid agents to get into Malaysia.

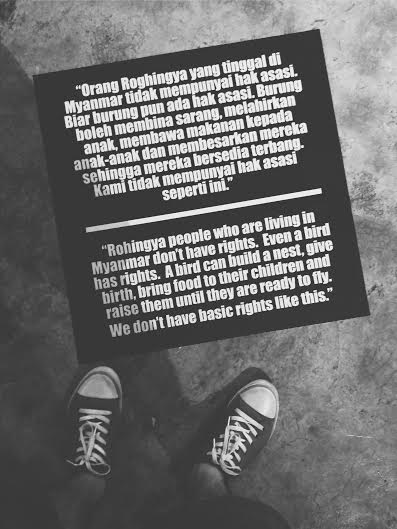

He shared that although the Rohingya plight and persecution are only being discussed extensively now, it is something that has been going on for a long time. He said that for a Rohingya to go from one kampung to another, he or she would have to apply and pay for a pass or permission letter. A Rohingya would also have to apply to get married – a process that can take up to three years.

When he was in secondary school, some teachers would discriminate against Rohingya students and fights between Rohingyas and Buddhists were not uncommon. But according to him, things have gotten much worse in recent times – for instance, Rohingya students can’t even attend university now.

The Burmese authorities also keep track of the amount of people in each household. But I was curious: what would happen if someone was missing from the household? For example, if me and you are living in the same house – I leave and you stay behind, what would happen to you?

I was expecting imprisonment, getting beaten up or something along those lines. But his answer turned out to be more shocking and painful. He said the authorities would question you and demand for some sort of a payment/fine. After that, the authorities will smile because that’s what they want to achieve anyway – Rohingyas out!

Briefly, Rohingyas are effectively stateless in Myanmar due to the 1982 Citizenship Law. Thus, they have no or limited access to proper healthcare, education, and work opportunities (click here and here to read more). They also placed in Internally Displaced Person camps, referred to by New York Times as ‘quasi-concentration camps’.

Abdul also told me that he misses his kampung Sittwe in Myanmar and he sometimes cries just thinking about it – but he knows that he cannot go back. He just recently received his offer for resettlement in the US and although he feels reluctant to leave his leadership role here, he said he will leave so his son can have better access to education.

On the other hand, John (not his real name) is a Chin refugee (majority of Chins are Christians) who has been in Malaysia for about seven years now.

Considering how the Rohingyas have been the focus of the media, it is important to note that Christians also to some extent, face persecution and much discrimination from the Burmese government, which compels them to flee their country. In 2007, a leaked document showed the miltary regime’s intent to wipe out Christianity in Burma. You can read a related Human Rights Watch report here.

He shared with me that in hilly Chin state, each household had to send a representative to be a porter of heavy military equipment for the military. Sometimes, a woman or a really young person would have to do it, in the absence of older males in a household.

Discrimination was prevalent, and he said that if you were a Christian in the military, you won’t be promoted. Safety was not secured – getting beaten up and sexual harassment and violence against women were not uncommon. This discrimination and persecution against Christians was all the more extreme a few years ago – but tensions still very much exist.

Regardless, John shared that he cannot go back to Burma – if he does and if the government found out, he would be faced with imprisonment or some other type of persecution.

So why do refugees choose Malaysia?

Although Malaysia didn’t and doesn’t plan to be a signatory of the UN convention and protocol that are related to refugees, we’re not that bad.

There is a total of 152,570 refugees and asylum seekers registered with UNHCR Malaysia, as of February 2015 – and the majority of them are from Myanmar. So if we’re not a signatory, why do they come here? How does it work?

- We still kinda accept refugees and allow them to stay in Malaysia on humanitarian reasons.

- We function as a ‘transit country’, which is that country that is not your home country and not your third country (third country is the country that you will be resettled in – countries that are part of the UN refugee convention).

- Refugees and asylum seekers are have right to access health care services in hospitals and government clinics. Refugees are also entitled to a 50% discount off the foreigners’ rate, while asylum seekers are not. (Source: Parliamentary Hansard – did you know that these documents are available to the public?)

But there’s still trouble in (semi-)paradise…

As a ‘transit country’, we still make things pretty difficult for these asylum seekers and refugees, specifically with two things:

1. Their right to work on our land

Refugees and asylum seekers legally do not have the right to work – and so, when it comes to working, they are often grouped with “illegal immigrants” under the Immigration Act 1959/63.

They still need to work to earn money, so they work anyway without having the legal right to work. This then can lead to *surprise surprise* low wages, working extra long hours, withholding wages… All that bad stuff. Naturally they end up working in the informal sector, which people then argue that they “steal jobs from Malaysians”.

I would now like to unleash my Chicken Chop & Broccoli™ analogy:

You have chicken chop with a side of broccoli. You love and want the chicken chop (because I mean, who doesn’t? sorry, vegetarians and vegans). And you absolutely detest broccoli and don’t want it anyway. So when your dining partner takes the broccoli from you and does you a favor of consuming it – is it “stealing”?

Revelation coming up… *suspense* The chicken chop represents the jobs that Malaysians want and work towards, while the broccoli represents the 3D (Dirty, Dangerous, Difficult) jobs. So unless Malaysians would want to take up these 3D jobs, I don’t think that argument holds much weight.

2. Access to formal education

According to UNHCR, there are about 13,500 school-going-age refugee children in Malaysia and these students do not have access to formal education – and so, they would have to study in private schools that are set up by volunteers or refugee communities. These schools are almost always funded by donations. Petra Gimbad, a writer and activist, tells CILISOS that it is uncommon for Malaysia underprivileged kids to also be enrolled in such “refugee” schools.

From my experience in refugee schools, Malaysians and the expat community in Malaysia are generally quite compassionate and caring – so yay us! If you are up for a good tearjerker documentary – check out Hashim’s School of Hope. Here’s another that is equally informative, but less of a tearjerker – Malaysia’s Unwanted. (Shoutout: Refugee schools are always in need of more volunteers, so if you are interested, here!)

So what can we Malaysians do now?

It is good news that Malaysia has agreed to accept the recent “boat people”, but it is quite worrying that we have set a ‘one year’ timeline for resettlement or repatriation, as repatriation is not a feasible option for Rohingya refugees.

The solution to this Rohingya problem and generally, the problems of the Burmese government with religious minorities ultimately, has to come from within Myanmar and this will only happen if all countries pressure them. This is not just a regional issue, but a truly global issue. Agreeably, this is much easier said than done – but hopefully, Myanmar’s agreement to attend meeting on this crisis is a sign of better things to come.

Ultimately, with all matters related to refugees, we need to be more sympathetic and empathetic towards them – and more importantly, we need to have laws that reflect such. I have successfully avoided using ‘human rights’ in the bulk of this article because the usage of ‘human rights’ often makes us just go like this:

So maybe let’s take another approach – let’s be kinder to refugees because they are humans and it’s the right thing to do.

My friend, Tim once said, “Geography is destiny”, which can be a terribly ugly and painful truth for those living in difficult geographical contexts. So when people come into our “geographical context” in search of a better destiny, maybe we should be more helpful. Because after all…

At the end of the day, we must also never forget that as a nation, we are not defined by what the Burmese government does to its people or how other countries react to refugees, but rather, we are defined by what we do and what we do not.

- 631Shares

- Facebook621

- Twitter1

- Email1

- WhatsApp3