Apa ni Social Contract? 8 ways to understand your racial role in Malaysia

- 1.4KShares

- Facebook1.3K

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn9

- Email15

- WhatsApp33

This article was originally written in 2015.

Recently, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department P Waythamoorthy restarted conversations to sign the United Nation’s International Convention on Eliminating Racial Discrimination (ICERD). Unfortunately, one of the conditions is for there to be no racially-based policies, which Malaysia does have. Many people have objected to this ratification, one of whom, is Khairy Jamaluddin, who said there are reasons why we haven’t signed this UN convention before.

In 2015, Khairy Jamaluddin shocked his many supporters by bringing up Malaysia’s social contract – and by seeming to show support for the special privileges of Malays.

While we believe much of what he said was taken out of context, it did make us realise one thing: There are lots of Malaysians out there clueless about our Constitution, the social contract, and how this affects us all on a daily basis.

Before you go out and start slogging through the many pages of jargon that make up our Federal Constitution though (trust us, it’s pretty headache-inducing), not to worry: We’ve done it for you! Here’s a handy-dandy cheat sheet of 8 points you need to know to understand the mysterious Social Contract.

1. It doesn’t mean what you think it means.

The truth is, the term “social contract” (which beeteedubs, isn’t even a term used in the Constitution) has a much more general meaning:

“The social contract is essentially a legal concept. In exchange for the protection of the state, citizens consent to surrender a certain extent of their rights by allowing themselves to be subject to the laws of the sovereign. These laws may prevent them from enjoying absolute freedom but they are necessary in order for citizens to be able to live in a civil society.” – Firdaus Husni, lawyer and Chairperson of the Malaysian Bar’s Constitutional Law Committee

In plain English, that means as citizens of Malaysia, we agree to give up some of our freedom to comply with the country’s laws, and this stops us from descending into absolute chaos (come on – just think about a country where NO LAWS exist. Havoc right?).

In Malaysia, though, people who talk about the social contract are referring to a deal the government struck back in the day so that Bumiputeras and non-Bumiputeras could live together in peace and harmony. Specifically, they’re talking about Articles 14–18 of the Constitution, which grants citizenship to non-Bumiputeras (particularly the Chinese and Indians), and especially, they’re talking about Article 153, which grants the Malays special privileges.

If you feel like being intellectual and lawyerly, the full text of the Malaysian Constitution can be read here.

2. But the true meaning of it has been somewhat skewed in recent years.

Sure, Article 153 talks about special privileges for Malays. But it was also amended after Sabah and Sarawak joined Malaya to include the Orang Asli, and it talks about making sure the interests of other communities are also taken care of:

“It shall be the responsibility of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to safeguard the special position of the Malays and natives of any of the States of Sabah and Sarawak and the legitimate interests of other communities in accordance with the provisions of this Article.”

There’s a difference between the word “privileges”, which is what the Constitution uses, versus the word “rights.”

“The difference is more than semantics. A right implies something inalienable. A privilege on the other hand is a benefit, presumably given to those who need it.” – Prof Madya Dr Azmi Sharom in a letter to The Sun

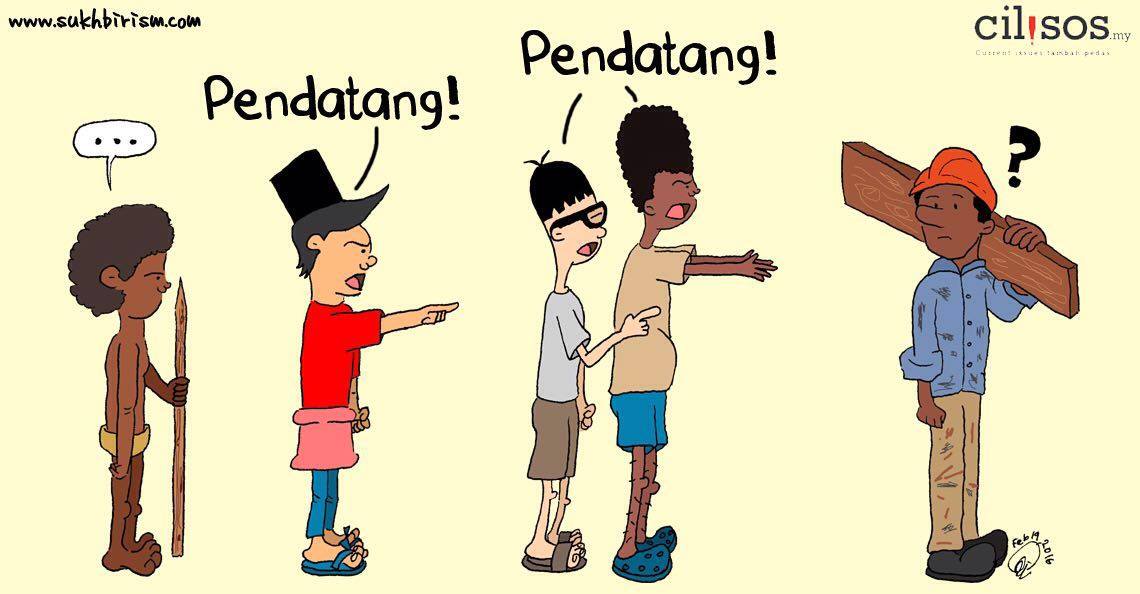

3. We seem to have forgotten our other Bumiputera peeps – the Orang Asli.

Read that bit we quoted above again and then tell us if we missed something. Why is nobody talking about the special rights of the Orang Asli? Why is nobody waving any kerises on their behalf or launching campaigns to make sure their special position stays…well…special?

Oh that’s right. It’s because somehow, we’ve conveniently forgotten that Article 153 is also supposed to extend to our other Bumiputera brothers and sisters – you know, the actual natives of the country.

“The social contract is not a bad concept in its entirety. But only certain parts of it are emphasised upon by political parties, so much so that it has taken a life of its own, and that what political leaders now claim as the social contract no longer reflect the intention of our forefathers and the framers of the Constitution; that is, among others, to address the disadvantaged groups of the society to promote a wholesome development.” – Firdaus

4. It made sense at the time.

“As is the fate of all social bargains, once the original authors pass from the scene, the descendants do not always appreciate the rationale behind the original compromises.” – Dr Shad Saleem Faruqi, Professor of Law at UiTM.

Okay, let us break this down for you with a simple analogy.

Say you teach a class of 20 kids, and you’ve taught them for a few years now, and you have a certain comfort level with them. Then suddenly you’re give an additional 15 kids to put in with the same class. You don’t know much about these new kids, but you do know that you’re expected to stretch the same amount of resources you always had for 20 kids to now, 35 kids.

You worry that your original 20 may be deprived of some things, which doesn’t seem fair when they were there first, so until they all learn to get along and share your resources you put a couple of rules in place. Maybe your original 20 get a special section of the class to sit in, or maybe they get a certain share of your nice new books compared to the other kids, or maybe they get to go to recess 10 minutes earlier so they can be done eating by the time the other kids come out and have a shot at playing with the good toys.

Eventually, after a couple of weeks, you phase out these rules, gradually letting the kids mingle more, introducing activities they all can do together, and sharing out resources fairly so that everyone gets to participate in classroom activities.

Geddit? The Constitution (and the government) is the teacher, and the rakyat are the kids. The only problem is that we’re still stuck in segregated groups, watching some kids leave for recess early or sit in their special spots while the rest of us wait our turn. Which brings us to our next point…

5. It isn’t supposed to exist anymore.

Okay murid-murid, time for our Sejarah lesson of the day.

In 1956, a fella called Lord William Reid was appointed to create a report that would become the basis for a Malayan Constitution. This became known as the Reid Commission (duh) and can be read here (warning: also quite headache-inducing if you’re not of the lawyerly persuasion).

Part of this included many, many conversations with Tunku Abdul Rahman and the Malay Rulers. At the time, Tunku was the leader of UMNO, which lead the Alliance coalition (which would eventually become Barisan Nasional). Tunku had expressed doubts about the loyalty of the non-Malays to Malaya, and as a result, insisted that this be settled before they be granted citizenship.

So basically, after doing a lot of digging and asking around and whatnot, the Reid commission reported that “provision should be made in the Constitution for the ‘safeguarding of the special position of the Malays and the legitimate interests of the other Communities’.” This became what we know as Article 153.

However, this is key:

“…in due course the present preferences should be reduced and should ultimately cease.” The Commission suggested that these provisions be revisited in 15 years, a report should be made to Parliament, and that the “legislature should then determine either to retain or to reduce any quota or to discontinue it entirely.”

For whatever reason, unfortunately, this review didn’t happen. In fact, thanks to the New Economic Policy (NEP) introduced after the racial riots of the May 13 Incident, Bumiputra privileges were actually extended to other areas: quotas are set for Bumiputra equity in publicly traded corporations, and discounts for them on automobiles and real estate ranging from 5% to 15% are mandated.

In other words, we’ve still got some rakyats sitting in the classroom, waiting for their turn to play in the playground.

6. It’s a huge part of the reason we are the nation we are today.

C’mon guys, if the deal about citizenship hadn’t been struck, we wouldn’t be the multi-cultural nation we are today! We wouldn’t be the melting pot of cultures, languages and of course, food (MMM, FOOOOD) that makes us so uniquely Malaysian. This is something we should be grateful to our forefathers for forging for us – our national identity.

Unfortunately, of course, there are the bad bits. We can’t deny that the loose, open-to-interpretation wording of the Constitution has allowed what some perceive as race-based politics to fester, leading to comments like those recently made by Home Minister and UMNO Vice President Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi:

“Don’t try to disturb these four key thrusts [Islam as the official religion in the federal region, Malay Rulers, Malay rights and Malay Language as the national language] because we, UMNO, and the government, will ensure that the stern legal action will be taken against those who dare to do so… I would like to stress here that there will be no compromise in this matter and to whom it may concern, don’t try to challenge the Federal Constitution.”

7. It doesn’t really meet international standards.

Recently, a study was released by the UK-based Equal Rights Trust along with Tenaganita showed that there are many points in our Constitution that promote racism or do not meet international law standards.

“Washing the Tigers [that’s the name of the study] finds that the problems which the Bersih movement identifies with the political system are symptomatic of deep-rooted inequalities which limit people’s rights and aspirations in this Asian Tiger nation.” – report released by the Equal Rights Trust in conjunction with Tenaganita

“International standards would require that any affirmative action policies conform to the principle of fairness, proportionality, legitimacy of purpose, and that it must be temporary,” says Firdaus. “Unfortunately, Article 153 and other provisions giving priorities to only one section of the society are seen as permanent. Worst, these provisions are used to justify the concept of ‘Malay supremacy.’

While I may not necessarily agree that some points promote racism, I agree that they do not meet the international law standards, and in the non-compliance of those standards, we have in actual fact promoted racism.”

8. It can be amended.

At this point, most people who made it this far (CONGRATULATIONS! HAVE A COOKIE!) will probably be wondering “Eh, if it’s so bad and divisive, why don’t we just get rid of Article 153? We don’t need it anymore what!”

First of all, there are plenty of people who argue that we DO still need it, and that you CAN’T CHANGE OR QUESTION THE CONSTITUTION OMG SEDITIOUS DON’T LIKE LEAVE THE COUNTRY LAH (see Zahid’s comments in point 6 above).

But the truth is, the Constitution CAN and HAS been amended – many, many times. After all, our forefathers were smart fellas who realised that laws made in the early days of the country would have to evolve over time. “Yes, the Federal Constitution recognises that there may be instances where an amendment to the laws is necessary. However, there are safeguards in place to ensure that amendments cannot be easily made,” explains Firdaus. “As at 2005, there have been more than 650 individual amendments made to the Constitution. The number is staggering compared to other countries.” (By comparison, from the 11,539 proposals to amend the United States Constitution since 1789, only 33 have made it as amendments).

——

Seriously though? Why should we care? The Constitution is just an old document a lot of people made up a long time ago what.

Yes, but it was created to essentially CREATE OUR COUNTRY. We need to know about our Constitution so we know when our rights are being stepped on – and defend them accordingly.

“Our Constitution matters because it belongs to all,” says Firdaus. “It seeks to protect the interest of all Malaysian citizens, not just a certain section of the society. It is in the Constitution that our rights are guaranteed, that the powers of government institutions and limit of those powers are set out.

The average Malaysians therefore must empower themselves with the knowledge of the Constitution so that they will not be easily misled by skewed constitutional interpretations, so that there will not come a day when we realise that our rights in its true sense and the safeguards from unjust government are no longer in the Constitution, and that it is too late to change that.”

And in the words of a poem by Charles Bukowski, “there is nothing worse than too late.”

(Ed’s note: This article was originally published mid-December 2014 and republished on 9th Feb 2015)

- 1.4KShares

- Facebook1.3K

- Twitter4

- LinkedIn9

- Email15

- WhatsApp33