This tiny island in Malaysia harbours a chilling, dark secret that not many know about

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.2K

- Twitter28

- LinkedIn23

- Email29

- WhatsApp140

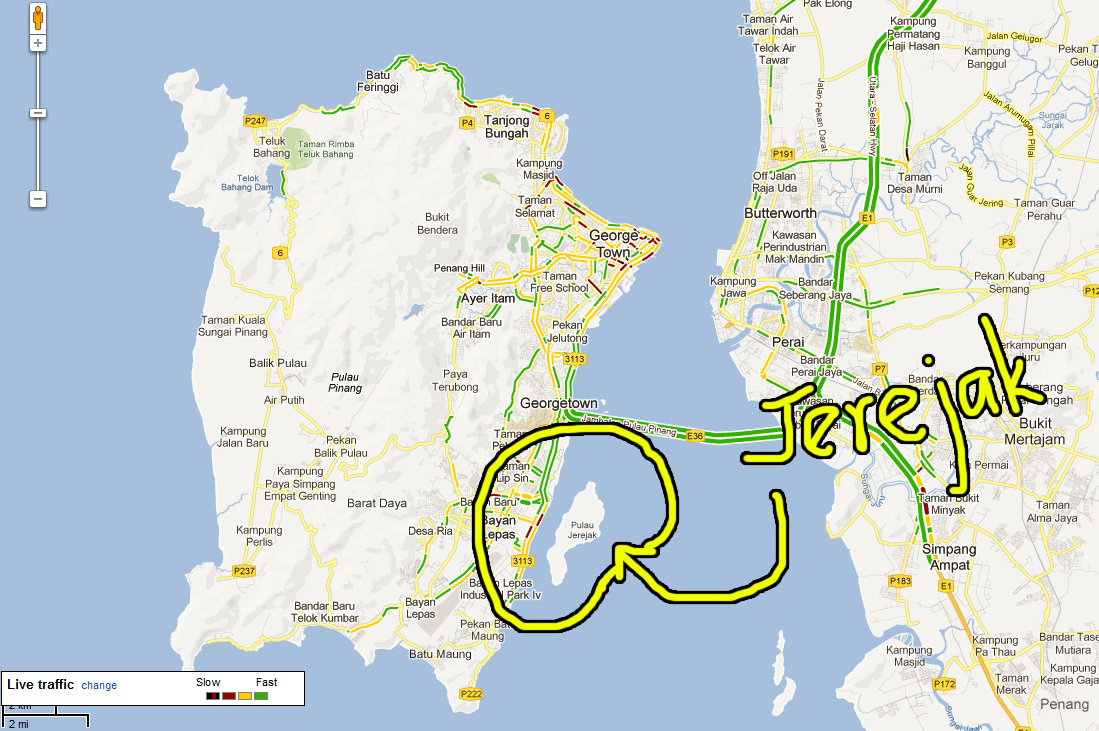

For some reason, when someone says ‘let’s go to Penang’, not many people would think of the mainland part. And even less people would think of the tiny island next to the bigger island, Pulau Jerejak.

At first glance, it may seem like there’s nothing on the island except a jetty and some run-down buildings (plus forests)… so why are heritage activists pushing for the island to be preserved and recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site?

In fact, standing at3.62 km², what’s so special about this teeny tiny piece of land to warrant this quote from a history scholar?

“Jerejak has more history per square inch than most other places in Malaysia.” – Michael Gibby, a scholar who has done two years of research on the history of the island

Whoa. So what kind of history are we talking about here? Well, first and foremost…

1. It was once CRAMMED with people who suffered from leprosy and tuberculosis

In case you’re not familiar with the disease, leprosy is when a type of bacteria (Mycobacterium leprae) infects people and causes them to have terrible, terrible symptoms that are hard to miss, like this:

People were generally scared of lepers (people with leprosy), and the standard thing to do back then was put them somewhere far away from the rest of the population, as it was believed that leprosy spread through touch. There was no cure for leprosy until the 1940s, so people with leprosy had to walk around looking like that. In 1926, the Leper Enactment Act was established, and people had to notify the existence of lepers to the government, and they had to be isolated.

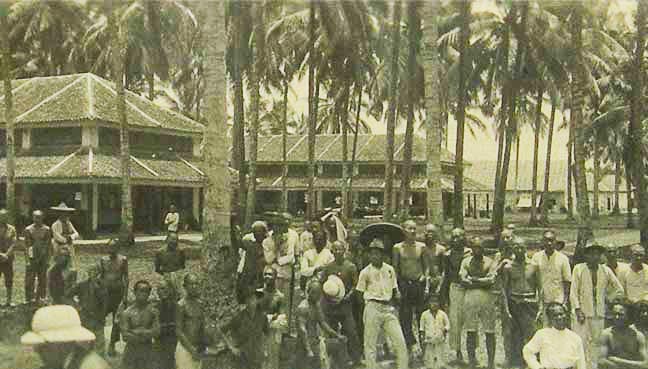

Malaysia had two places where lepers were held. One of them was the Sungai Buloh Leprosarium, established in 1930. The other one was on Pulau Jerejak, and it was established even earlier in 1868, using money collected from Chinese businessmen in Penang. But lepers in Penang had isolated themselves on Jerejak even before then.

“The first 25 lepers moved into the building on a voluntary basis, before the island was recognized as a leprosarium. It once housed more than 7,000 lepers,” – Michael Gibby, to FMT.

Sometime before independence, another infectious disease hit Penang, and it was tuberculosis (TB), a disease spread through coughing. So people with tuberculosis were rounded up and crammed together on Jerejak together with the lepers, but on opposite shores of the island, of course. So in 1948, a TB sanatorium was built on the southern part of the island.

As research on leprosy progressed, people realized that you can’t get it by touching lepers, and a treatment for the condition was discovered, so around the world leprosariums were slowly abandoned. The same goes for Malaysia. In 1969, the National Leprosy Control program was launched, and treatment for leprosy were decentralized, meaning that leprosy is now treated like any other disease you go to the doctor to.

Also in 1969, the 7,000 or so lepers in Jerejak were transferred to Sungai Buloh, as…

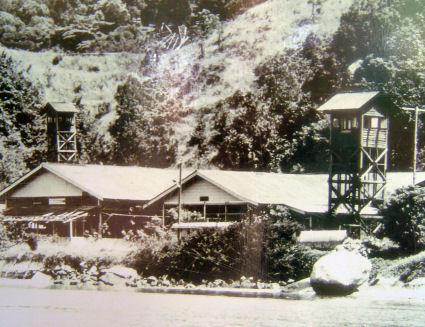

2. Pulau Jerejak became a place for prisoners

There’s a source that said Jerejak used to house Asian war prisoners before letting them go back to their home countries after Japan surrendered in 1945. Another source had said that Jerejak became a prison since 1948, as a place for the British to detain political prisoners. However, several sources had said that the Pulau Jerejak Correctional Facility (Pusat Pemulihan Pulau Jerejak) started its operation in June 1969, under the Prisons Department of Malaysia.

[UPDATE 27/7/2018: Rexy Prakash Chacko, one of the people who have done research on the island, clarified to us that after the second World War up until 1948, Pulau Jerejak had been the place where the British kept communists like Rashid Maidin. Thanks! 🙂 ]

In case the date hadn’t tipped you off already, the Jerejak Prison housed those arrested under the Emergency Ordinance (Public Order and Crime Prevention) 1969, which came from the May 13th incident. It allows people to be detained without trial, so you can perhaps imagine what went on on that island. It was also said to house convicts under the Dangerous Drugs Act (Special Preventive Measures) 1985, so besides political prisoners, there were probably drug dealers/traffickers/users in the same facility, too.

Perhaps the only noteworthy incident that happened during Jerejak’s time as a prison was a riot in 1981, when 100 inmates protested their sudden extension of sentence by destroying part of the prison buildings, but not much else can be found about the place. It eventually closed down in 1993 to make way for Penang’s development plans for the island, and the remaining prisoners were transferred over to the Muar Correctional Facility in Johor.

3. Two forgotten World War I Russian soldiers were buried there

You might be wondering… when did Russians fight on Malaya? Well, actually it’s a story that happened during World War 1, and we’ve actually written about the Battle of Penang before. It was one of the few WW1 battles fought where present-day Malaysia stands, but it was more of a slaughter rather than a battle, actually. At that time, the British was in occupation of Penang, and Russia and France were her allies, so French and Russian ships would frequent Penang.

The two soldiers buried in Jerejak belonged to the Russian cruiser named Zhemchug (Pearls), and they were attacked by a German ship called Emden, which was on a solo mission to harass British ports in the area. The command of the Zhemchug was said to be really negligent at that time, and they stopped at Penang to perform major maintenance on the ship, removing much of their combat abilities. It was said that during the attack, the captain of the ship was spending the night on land in Penang, presumably with his wife (or mistress).

Anyway, the crew realized Emden’s presence too late (Emden disguised itself as a Russian ship as it sneaked up to the moored Zhemchug, plus there were no night guards), so the Zhemchug sank with just two shots from Emden. Of the 250 people on Zhemchug, 85 died in the attack, and 26 bodies were recovered by the local fishermen. 24 of them were buried in an old Catholic cemetery on Western Road in Penang, but somehow two got recovered separately and were buried on Pulau Jerejak.

The Russian Stone (Batu Russia) on Pulau Jerejak is where the two sailors from the Zhemchug were buried, but the cemetery was said to have been abandoned for a long time until the Russian Embassy cleaned it up in 2006. However, the anchor and chain on the memorial was said to have been stolen by vandals, and presumably sold for scrap metal.

4. There were detention centers for immigrants and people returning from Mecca

Remember the Michael Gibby (heh, Jibby) guy we spoke of earlier? One of the main findings from his two years of research was that Pulau Jerejak served as a sort of filter to the rest of Malaya since the 1870s. There was a sort of fear of infectious diseases back then, which may or may not have something to do with Francis Light clearing the forests on Penang and his eventual death from malaria.

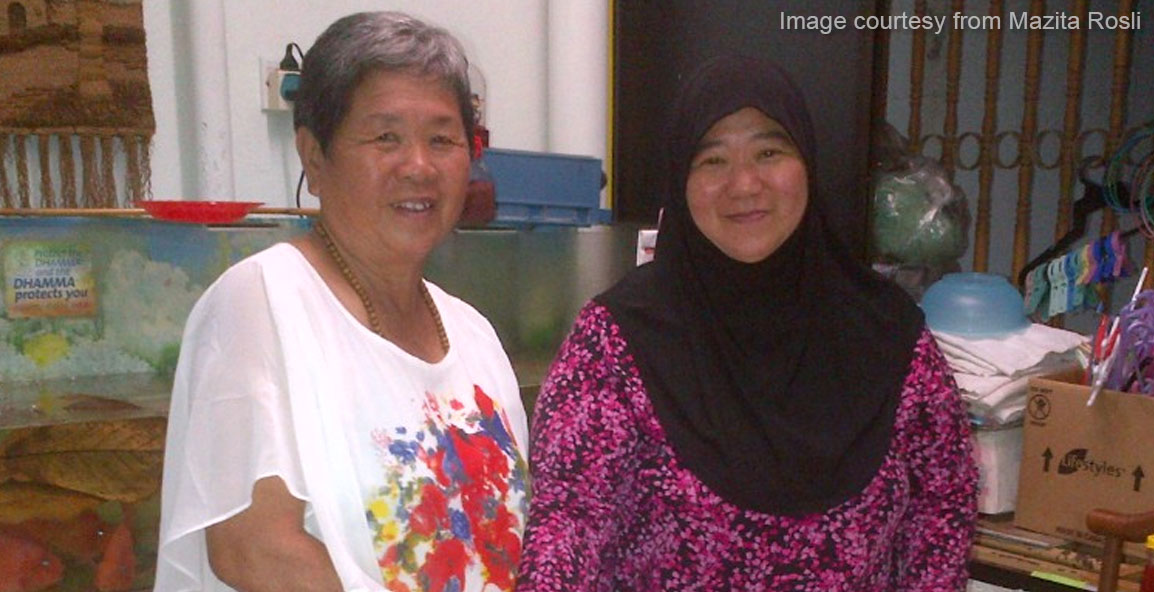

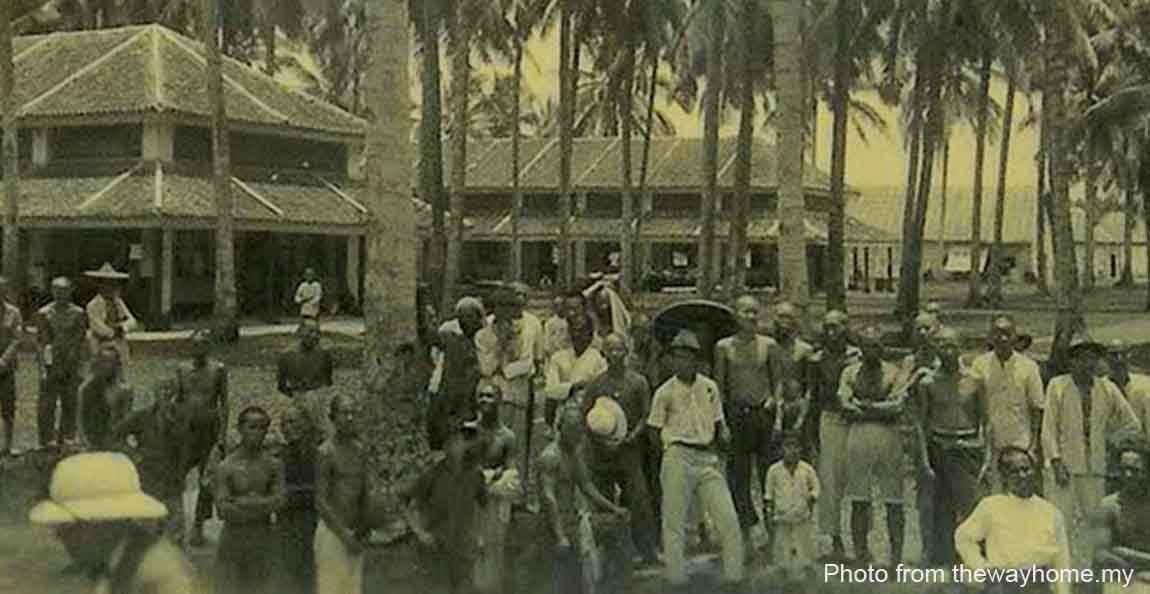

Anyway, together with Singapore and later, Port Klang, Pulau Jerejak became the de facto gateway to the rest of Malaya, and every immigrant entered through one of these three ports. Gibby found that from 1877 up until the second World War, a total of 1.13 million people were quarantined before allowed access to Penang and the rest of Malaya, and most of them came from the Indian sub-continent, China, and even Malayans returning from Mecca by sea.

A building complex, believed to be the quarantine center, was built in 1875 to house these people.

“If you were born in Penang, there is a good chance your great-great grandfather had once stepped foot on Jerejak before going anywhere else in Malaya. Muslims who went to Mecca for haj and returned were also required to be checked at the quarantine there… They were quarantined until the infectious period was over. There was strict adherence to health rules then,” – Michael Gibby, to FMT.

The Malayans returning from Mecca thing happened during the 1930s-1940s, and it was said that the hajj-goers were not pleased with the procedure, as they were already vaccinated before leaving. One woman who went to hajj in 1936 recounted that they had to be transferred from the Mecca ship to a speedboat to get on to Jerejak (some of them fell into the sea during the process), where they may be detained for two to three hours, during which they were stripped naked and apparently steamed before being released.

Huh. Jerejak used to be a place to hold diseased people, have graves of different ethnicities strewn across the island and used to be a prison, where a riot took place. Sounds like a delightful place, which is perhaps why…

Penang has been trying to turn it into a tourism spot for years

In 2004, a resort was built where the leprosarium once stood. The Jerejak Rainforest Resort and Spa was opened at the cost of RM30.3 million, but was later closed down in 2016 due to losses amounting to RM40 million. Since then, the issue of Pulau Jerejak had been a sore spot between conservationists and the state government. In 2015, there were accusations of the state government selling off the island to private developers, but the Penang Development Corporation’s (PDC) stakes on an 80-acre lot on the island were just sold to UDA Holdings Bhd.

UDA had in 2017 announced that it had entered a joint-venture agreement with another company to redevelop the Jerejak Rainforest Resort & Spa, which will include 1,200 residential units, a theme park, a marina, hotels, and a cycling track, and in May this year, the Penang Island City Council (MBPP) had given the go-ahead to demolish existing building structures on Jerejak to make way for the resort, with the condition that development does not encroach into the island’s forest reserves.

People who see Jerejak as a treasure trove of history and heritage had tried to stop it, but to no avail. In 2017 an International Petition was launched to save Pulau Jerejak from development by the Sungai Buloh Settlement Council, and at the time it was launched it had the support of more than 30 participants from 16 countries. Which was kinda impressive for a non-online petition, but it seemed that it wasn’t enough to stop it.

Now, the National Heritage Department is trying to apply for a UNESCO World Heritage status for Pulau Jerejak, and they will be writing the Penang’s new Chief Minister Chow Kon Yeow about it next week. But will that be enough to stop Jerejak’s development? Only time will tell. But will it be worth stopping development for the sake of history?

- 2.5KShares

- Facebook2.2K

- Twitter28

- LinkedIn23

- Email29

- WhatsApp140