The science behind Sang Kelembai’s myth, the Malaysian giant who turned creatures to stone

- 645Shares

- Facebook628

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn4

- Email3

- WhatsApp7

If you think about the myth of people turning into stones, many would probably think of the Gorgon sisters, specifically Medusa. These ugly, snake haired monsters were said to be able to turn anyone into stone simply by having them look into their eyes.

But Malaysian mythology surprisingly had a lot of people turning into stones as well, mainly through curses. Most of the stories have some sort of moral implication behind them. For example, in the legend of Si Tanggang, a poor boy left his home village and became wealthy, but he grew arrogant and refused to recognize his own shabby parents when he returned. He promptly got cursed to become a stone by his mother.

In the legend of Batu Kudik in Sarawak, a partying longhouse insulted a grandma and her granddaughter and drove them off when they asked for food. The duo got angry and cast a curse on the longhouse, causing all the guests to turn into stone. These stories have a moral to them: don’t be a prick if you don’t want to be a brick.

But not all folk stories have a lesson. Sometimes, they serve to explain how something became the way it does, and these are called origin myths. One such myth was about a particular beast roaming Peninsular Malaysia in the old days, and her name was Sang Kelembai.

Sang Kelembai was a giantess who kept accidentally turning people into stone

Just like Sang Kancil, there are many stories regarding Sang Kelembai, and just as many depictions of her. Details about her vary from story to story: some say she’s an ugly giant, others say she’s a luscious woman; some say she can fly, others describe her as a ghost. But there’s one thing in common when it comes to Sang Kelembai (or Gedembai in the northern regions): she can turn people and animals into stone, simply by speaking to them.

This seems to happen whether she likes it or not. Some of her stories involve accidentally turning whole villages into stone without meaning to. She once went to a village where a feast was being held, and smelling something nice coming from the kitchens, she asked the cook what’s cooking. The cook immediately turned to stone. Horrified by what she’d done, she went out and apologized to the feast’s guests, only to have them all turn into stone.

Sang Kelembai wasn’t described as a malicious being, so she lived an existence of loneliness and self-loathing because of her power. She would wander from place to place in the Peninsula, trying her best to not speak to anyone, but eventually having to speak anyway. For instance, she once stumbled into a man cooking broth in the middle of the jungle. The man invited her to join him, but, fearful for the man’s well-being, she tried to run away. She tripped and fell, however, and she accidentally blurted out the man’s invitation back to him, turning him to stone.

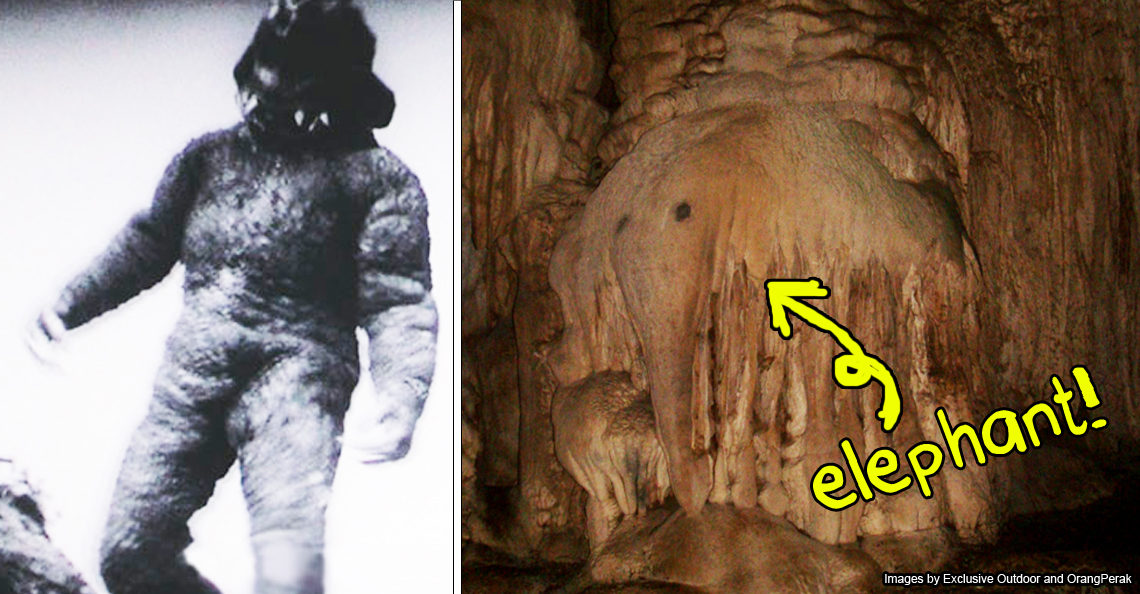

Due to the nature of her power, she had been used to explain a lot of weirdly-shaped stones around the Peninsular. Batu Gajah in Perak was so named because she cursed three gossiping elephants there, and Kampung Batu Talam in Pahang was named because people found stones shaped like trays there, believed to be her doing. The Kota Gelanggi Cave in Pahang was filled with various stones shaped like animals and people, and it was said that these were the people involved in a war over a woman some time back, which ended when Sang Kelembai commented on how weird the reason for the war was.

The Gua Kerbau in Kedah was so named because there’s a stone that looks like a buffalo in the cave, and we suppose you can guess how that happened by now. There are a lot more similar stories regarding Sang Kelembai’s curse out there, so if it’s a stone shaped like people somewhere on the Peninsular, you can just say that Sang Kelembai probably had something to do with it.

“So if you come across any stone in the shape of an animal or human nowadays, then you cannot be far wrong if you guess that it was caused by the curse of Gedembai a long, long time ago.” – excerpt from ‘The Legends of Langkawi‘, by Mohamed Zahir Haji Ismail.

Regardless of whether or not you believe in Sang Kelembai, you might have noticed something strange with all these stories by now…

Wait a minute. Why do we have so many weirdly-shaped stones lying around?

If there’s anything to take from the stories of Sang Kelembai, it’s that stones shaped like humans and animals seem to be so common in Malaysia that we came up with a boogeyman (boogeywoman?) and other myths specifically to explain them. We could chalk it up to our overactive imagination (Sang Kelembai’s backstory was pretty detailed, after all), but we should note that we’re not the only ones seeing weirdly-shaped stones. They’re so common that there’s a term for such stones: mimetoliths.

Remember the Si Tanggang story we mentioned earlier? Indonesia and Brunei have their own versions of the same myth, called Malim Kundang and Nakhoda Manis, respectively. All these Tanggang variations have allegedly left behind a stone or rock in their respective countries that proved their Tanggang’s existence. For the Malaysian Tanggang, the rock that used to be Tanggang’s ship is said to be Batu Caves, as Batu Caves was previously known as Kapal Si Tanggang.

Indonesia also have their own version of Sang Kelembai, except it’s a guy called Si Pahit Lidah (One with the Bitter Tongue) who, in one story, cursed a whole side of a swamp to turn into stone because nobody helped him cross the swamp. So what’s up with all the mimetoliths we have lying around? Well, there might be a scientific explanation for that. If we look at all these legends and the stones said to be cursed people, there’s one thing in common: most, if not all of them, seem to be of limestone.

Limestone is a sedimentary rock, meaning that it’s formed from the sediment from all the shells and corals that broke down a long time ago and was compressed over time. When compressed even further, limestone morphs into marble. Areas with tropical, shallow seas make a lot of limestone, which is perhaps why Malaysia as well as our neighboring countries have plenty of them. In the Peninsular alone, a 2016 study found that there’s at least 445 limestone hills, many of them found in Perlis, Perak, Kelantan, and Pahang.

While other rocks can form into weird shapes as well, limestone have some unique features that give them unique shapes. For one thing…

Limestone can be (relatively) easily eroded by rainwater

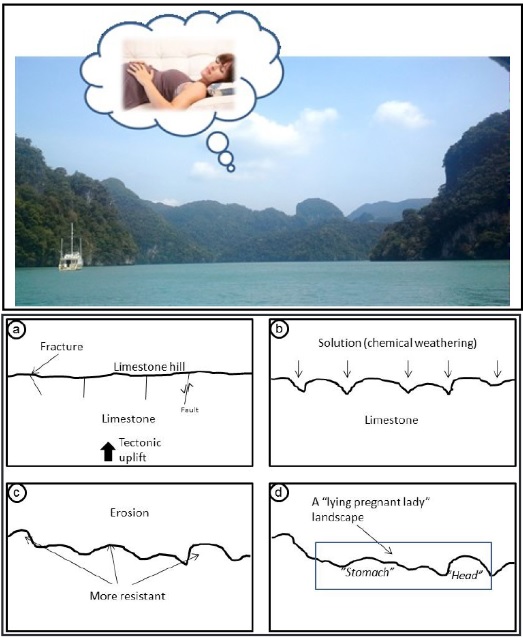

Limestone is mainly made of a chemical called calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is basic. Rainwater (and water in general), on the other hand, is slightly acidic when exposed to carbon dioxide in the air (forming carbonic acid). When limestones come into contact with weakly acidic water, it slowly dissolves, giving birth to the weird shapes we see in exposed limestone formations. For example, here’s how a 2017 paper hypothesized how the Pulau Dayang Bunting in Langkawi ended up looking like a pregnant lady.

Chunks of limestone often have layers and cracks in them, which is why some parts dissolve more readily than others. If you look at limestone hills in Ipoh, they often have very steep sides, which was a result of the layers being aligned vertically, and rainwater separating chunks from the sides. The jagged pinnacles in Mulu were also formed in roughly the same way. These are the big-scale limestone interactions with water.

For mimetoliths in caves, the same thing happens at a much smaller scale, except water doesn’t just fall from the above like rain: there’s dripping and streams and airflow and all sorts of complicated interactions between the limestone blocks and water, leading to the interesting shapes we see. So part of why we have so many weirdly-shaped rocks are scientific, and part of it is psychological, owing to our tendency to associate shapes with certain objects.

It’s probably way easier to explain them using a giantess with magical powers, anyway. However, despite the light-heartedness of the myth…

We could really use Sang Kelembai’s help now

As seen from the myths associated with them, limestones played a significant part in our culture. Unfortunately, limestone hills and forests are being threatened by quarrying and deforestation. Limestone is the raw material for cement, and of the 445 limestone hills on the Peninsular, 73 had been found to be affected by quarrying activities. Hills in National Parks are relatively safe from this threat, but for other places like Ipoh, there’s literally nothing stopping them from being quarried at the moment.

Over the years, conservationists have repeatedly called for greater protection for the limestone hills in Ipoh, with some suggesting for cement companies to dig for sub-surface limestone instead of carving visible hills for them. While it’s slightly more costly than blasting hills, the value in keeping the hills intact should be considered as well. For one thing, it seems there’s some historical value in the limestone hills of Ipoh.

“Limestone caves in Kinta Valley provide important links to our past. For example, I know of a lecturer in Kampar who is writing a paper on how Kinta Valley could have probably been submerged underwater in the past. This could be the reason why primitive men were probably able to write and draw so high up on cave walls.

“In fact, some Universiti Malaya (UM) scientists also discovered the fossil of an extinct elephant, Stegodon, at a limestone cave in Gopeng. It was the first stegodon fossil to have been discovered in our country. Unfortunately, our authorities give little attention to history. But, we need to remember that history cannot be replaced once it is lost,” – Goh Ah Poon, cave explorer, in an interview with New Straits Times.

Besides that, you don’t need to be a geologist to see how beautiful limestones can be, and how tourist spots like the geopark in Langkawi or Gua Tempurung in Perak can be built around limestone features. And because of their strange shapes and chemical structure, there are lots of animals and plants that can only be found in limestone forests and caves. Whether or not these are value enough for the authorities to do something about protecting our limestone hills will remain to be seen.

Until then, we can only hope that Sang Kelembai makes a comeback and starts turning random things into limestone.

- 645Shares

- Facebook628

- Twitter3

- LinkedIn4

- Email3

- WhatsApp7