Malaysians were angry at the RM50 salary increase, but they might be forgetting something…

- 200Shares

- Facebook174

- Twitter2

- LinkedIn2

- Email4

- WhatsApp18

Last Wednesday, more than 100 (some say 300) people gathered in front of our Parliament in a peaceful protest. Oh no, you might be thinking, what more do these people want?

Members of several NGOs, the Malaysian Trade Unions Congress (MTUC) and the Malaysian Socialist Party (PSM) gathered as early as 9.30 am and walked all the way to the Parliament to protest the government’s decision to raise the monthly minimum wage to RM1,050, and the hourly minimum wage to RM5.05.

While the actual decision was made in September, the date they picked (October 17th) coincided with the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, which MTUC secretary-general J Solomon said was apt as it symbolizes that the rakyat need a wage raise that’s suitable with current needs. Anyway, the march to Parliament was to hand over a memorandum asking the Prime Minister to reconsider the decision.

If you haven’t been following the minimum wage development for a while, you might have thought to yourself, eh, got pay raise. Ok what? But if you have indeed been following, you’d notice right away that…

That’s only a RM50 increase from the previous minimum wage

Well, for workers on the Peninsula anyway. For East Malaysia workers, that’s a RM130 increase, but we’ll get to that a bit. Anyway, that’s probably the main reason people are unhappy: after quite a long wait for the minimum wage to rise, the increase is about the same value as 5 tubes of toothpaste. The MTUC, for one, thinks that the increase is preposterous as the living costs are ever increasing.

“The Pakatan Harapan government is (the same as) the previous government that emphasizes sharing wealth with the society, but their actions don’t match what they said before. The excuse given, that productivity does not increase in line with salary, can no longer be accepted as worker productivity since 2000 had been very high… This is an unfair thing,” – J Solomon, MTUC Secretary-General, translated from Berita Harian.

S Arutchelvan, a PSM central committee member, divulged in a MalaysiaKini piece that PSM was among the bodies invited by the National Wages Consultative Council (NWCC, more on them later) to a special meeting to discuss the new minimum wage rate. However, while the NWCC had allegedly suggested RM1,170 as the national standard minimum, Prime Minister Mahathir had announced the rate to be RM1,050, which was allegedly the rate suggested by representatives of… employers.

This led PSM to say that Mahathir’s announcement is an insult to workers, and since the final decision was done by the Cabinet and not the NWCC, the NWCC should just resign as the decisions will be made by the employers and rich people only. And they’re not the only ones feeling that way, either.

“Even if the Government wants Peninsula and East Malaysia to have the same minimum wage, RM1,050 is still lower than the suggested RM1,170… This also indicate that they did not respect the findings of the council. Do the ministers not understand the predicament faced by the people? The protest today was to urge the ministers to review their decision,” – Soh Sook Hwa, one of the protesters on scene, to NST.

With the cause of discontent more or less hammered down, one might wonder…

Why poke a hornet’s nest in the first place?

With the response to the minimum pay, one might think that minimum wage is a touchy topic between workers, employers and the gomen… so why fix it if it ain’t broken? To answer this question, we’re taking a leaf (or two) out of PH’s book and just say that the previous government did it.

Before 2012, there was no such thing as a minimum pay: it’s all up to the bosses. A 2009 survey by the Human Resources Ministry revealed that a sizeable chunk of workers back then earned less than RM700 a month. For reference, you’re considered to be in poverty if your household earned less than RM800 then.

The government saw that, so during the dishing out of the 2011 Budget, Najib Razak (former PM) announced the setting up of the National Wages Consultative Council (NWCC), and from that a bunch of bureaucracy happened until the first Minimum Wage Order came into effect in January 2013. Workers in the Peninsular then could legally earn no less than RM900 a month (or RM4.33/hour), while workers in East Malaysia had a minimum pay of RM800 (or RM3.85/hour).

According to the Act that enabled the NWCC, the minimum wage is supposed to be reviewed at least once every two years (Section 25), so we saw another minimum wage increase came into force in 2016, where Peninsularians now earn at least RM1,000 per month (or RM4.81/hour) and East Malaysians earn at least RM920 per month (or RM4.42/hour).

Another two years had passed since then, so a minimum wage review should be around now. That’s one leaf. The other leaf we’re taking will be out of the Harapan Book, aka Pakatan’s manifesto. 5th on the list of things they promised within their first 100 days in power is standardizing minimum pay across the country as well as starting the process of increasing the minimum wage.

Technically, both East and West Malaysia will now have the same minimum wage starting next year, and the amount has been increased, however little. So unhappy or not, that’s a check right there. However, there’s a promise part two: Promise #34, which didn’t fall under the 100 day deadline, involves increasing the minimum pay to RM1,500 a month within their first term, or five years. To reduce the burden on employers, they have pledged to subsidize half the cost: if the pay is increased by RM500 for a worker, RM250 will come from the government’s pocket.

So generous! However…

The government can’t really afford to subsidize wage increases now

When we talk about raising the minimum wage, we’re not just talking about employers and the government paying a few hundred people extra. According to a nationwide survey done by the Institute of Labor Marker Information and Analysis (ILMIA) in 2016, about 60% of our companies employ workers on minimum wage. As for how many actually earn minimum wage, we, uh, can’t find the exact data on that. However, considering that half of our 8.7 million wage earners in 2017 earn less than RM2,160 a month and the other half earn a lot more than that (the median was RM2,880), we’d say the actual number is hella many.

So say that we do increase the minimum wage by RM500 for 3.5 million people. If the government is to payung half of that, they will have to fork out RM875 million a month, or RM10.5 billion a year. By comparison… remember the MyBrain15 program? It was supposed to help put some 10,600 through their postgraduate education, but it got frozen because the money allocated for it went missing. The budget for MyBrain15, at RM90 million, is more than a hundred times less than the RM10.5 billion, and the government can’t even afford that at the moment.

Mahathir himself had said that the government cannot afford to increase the minimum wage any further, and that they could not subsidize the increase at the moment. M Kulasegaran, the Human Resources Minister, had to his credit said that the paltry RM50 increase was not meant to belittle workers, but it’s just that the economy is growing pretty slowly, and people aren’t investing in Malaysia as much as before.

“All these are worrying factors, which we have to address first, besides the financial mess left behind by the previous government,” – M Kulasegaran, to FMT.

And it’s not easy for some employers, too, even when the minimum is RM1,050. East Malaysian employers, who have to increase minimum wages by RM130, had expressed their disagreement over the matter, saying that the infrastructure is not as good in Sabah and Sarawak as it is in the Peninsula. Higher basic wages would affect overtimes, increments and bonuses, which are all derived from it. The effects, according to the Malaysian Federation of Manufacturers, can potentially cause a company to restructure, which can potentially reduce employment opportunities.

It’s not just a hypothetical thing, either. A survey done on the effects of minimum wage back in 2016 found that to cope with the rising minimum wage, 61% of compliant companies saw lower profits, while 18% of employers cut back on other benefits for the workers (like allowances and bonuses), and 37% reduced the size of their workforce.

Changing the minimum wage seems like a delicate tightrope for the government to walk on, with both workers and employers just waiting to swoop in if the government is to lose its balance. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg, apparently.

To improve the labor situation, addressing the minimum wage is the… minimum

If you think that you need a Panadol to brain this whole minimum wage issue, you might need some morphine for the rest of it. Increasing the minimum wage itself is a good start – past increases contributed to a strong growth in private consumption, which is a major driver in Malaysia’s economic growth – but some felt that the issue runs deeper than the employers giving more.

Dr Muhammed Adbul Khalid, an economist, had said that rising living expenses should also be addressed, not just the minimum wage.

“Our minimum wage is about RM5 an hour. A litre of milk is between RM6.80 and RM7.50. For the minimum wage earners, you work one hour, you can’t afford a litre of milk. In Thailand, the price of milk is much cheaper and the poor only have to work half an hour to afford a litre of milk,” – Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid, as reported by The Star.

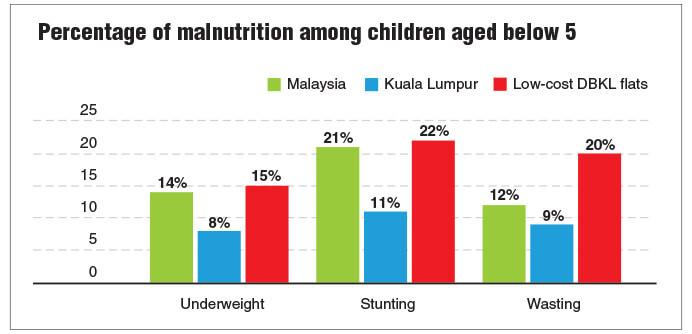

And although raising the minimum wage might reduce the number of people living in poverty (despite employers’ attempts to cope), some, like Dr Ong Kian Ming, felt that the poverty line in Malaysia is too low to be accurate. According to him, some households may not fall under the poverty line, but that might not mean that they’re not struggling. He noted how one in three households among the urban poor do not have a social safety net (insurance/Socso/EPF), and if their breadwinner suddenly cannot work, dies, or if one of the family members got a debilitating disease, they run a great risk of falling into poverty.

There’s also the issue of working hours in Malaysia, which according to Section 60A of the Employment Act, is actually 48 hours a week, up to eight hours a day, or six days a week. Minimum hourly rates are calculated by dividing the monthly rate into 26 8-hour days. So technically if you’re paid hourly but only work five days a week, you’d earn less than if you would on a monthly rate. But if you work six days a week… no work-life balance wei.

Lee Hwok Aun, of the Institute of SouthEast Asian Studies, had recommended that the legal working hours be reduced to 40, which would punish employers who continue to ask for six-day work weeks, as anything outside the 40 hours will count as overtime and will be 1.5 times the usual hourly pay. This, he believes, will apply greater pressure for them to raise productivity per hour, either through technological upgrades, innovation or workplace improvements.

There are other things we’d like to talk about when it comes to the issue of minimum wage, but you’ve probably got some idea of how complex it is by now. Getting back to the recent hullabaloo, after protests from so many people, M Kulasegaran had announced that the government had accepted the memorandum from the protesters and will be reviewing the decision.

Whether or not a new minimum wage will replace the RM1,050 will remain to be seen, but if the Pakatan is to fulfill its promise of RM1,500 minimum wage within 5 years, as evidenced by this recent reaction, it’s gonna be a bumpy road ahead, and they best fix the leaf springs on their bus soon.

- 200Shares

- Facebook174

- Twitter2

- LinkedIn2

- Email4

- WhatsApp18